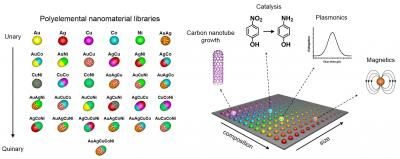

Core technology springs from nanoscale rods

Rice University scientists have discovered how to subtly change the interior structure of semi-hollow nanorods in a way that alters how they interact with light, and because the changes are reversible, the method could form the basis of a nanoscale switch with enormous potential.

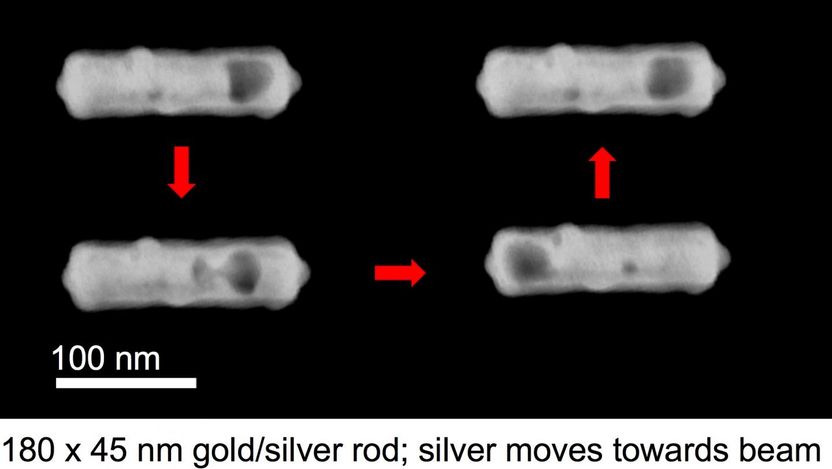

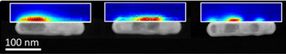

A sequence shows a single nanorod and how its core was restructured with an electron beam by scientists at Rice University. Liquid in the core could be turned to silver, which remained in place until reconfigured with the beam again.

Ringe Group/Rice University

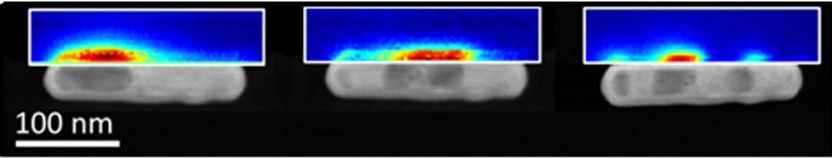

Reconfiguring the liquid core of a rod-shaped gold and silver nanoshell also changed its surface plasmon emissions, according to Rice University scientists.

Ringe Group/Rice University

"It's not 0-1, it's 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10," said Rice materials scientist Emilie Ringe, lead scientist on the project. "You can differentiate between multiple plasmonic states in a single particle. That gives you a kind of analog version of quantum states, but on a larger, more accessible scale."

Ringe and colleagues used an electron beam to move silver from one location to another inside gold-and-silver nanoparticles, something like a nanoscale Etch A Sketch. The result is a reconfigurable optical switch that may form the basis for a new type of multiple-state computer memory, sensor or catalyst.

At about 200 nanometers long, 500 of the metal rods placed end-to-end would span the width of a human hair. However, they are large in comparison with modern integrated circuits. Their multistate capabilities make them more like reprogrammable bar codes than simple memory bits, she said.

"No one has been able to reversibly change the shape of a single particle with the level of control we have, so we're really excited about this," Ringe said.

Altering a nanoparticle's internal structure also alters its external plasmonic response. Plasmons are the electrical ripples that propagate across the surface of metallic materials when excited by light, and their oscillations can be easily read with a spectrometer -- or even the human eye -- as they interact with visible light.

The Rice researchers found they could reconfigure nanoparticle cores with pinpoint precision. That means memories made of nanorods need not be merely on-off, Ringe said, because a particle can be programmed to emit many distinct plasmonic patterns.

The discovery came about when Ringe and her team, which manages Rice's advanced electron microscopy lab, were asked by her colleague and co-author Denis Boudreau, a professor at Laval University in Quebec, to characterize hollow nanorods made primarily of gold but containing silver.

"Most nanoshells are leaky," Ringe said. "They have pinholes. But we realized these nanorods were defect-free and contained pockets of water that were trapped inside when the particles were synthesized. We thought: We have something here."

Ringe and the study's lead author, Rice research scientist Sadegh Yazdi, quickly realized how they might manipulate the water. "Obviously, it's difficult to do chemistry there, because you can't put molecules into a sealed nanoshell. But we could put electrons in," she said.

Focusing a subnanometer electron beam on the interior cavity split the water and inserted solvated electrons - free electrons that can exist in a solution. "The electrons reacted directly with silver ions in the water, drawing them to the beam to form silver," Ringe said. The now-silver-poor liquid moved away from the beam, and its silver ions were replenished by a reaction of water-splitting byproducts with the solid silver in other parts of the rod.

"We actually were moving silver in the solution, reconfiguring it," she said. "Because it's a closed system, we weren't losing anything and we weren't gaining anything. We were just moving it around, and could do so as many times as we wished."

The researchers were then able to map the plasmon-induced near-field properties without disturbing the internal structure -- and that's when they realized the implications of their discovery.

"We made different shapes inside the nanorods, and because we specialize in plasmonics, we mapped the plasmons and it turned out to have a very nice effect," Ringe said. "We basically saw different electric-field distributions at different energies for different shapes." Numerical results provided by collaborators Nicolas Large of the University of Texas at San Antonio and George Schatz of Northwestern University helped explain the origin of the modes and how the presence of a water-filled pocket created a multitude of plasmons, she said.

The next challenge is to test nanoshells of other shapes and sizes, and to see if there are other ways to activate their switching potentials. Ringe suspects electron beams may remain the best and perhaps only way to catalyze reactions inside particles, and she is hopeful.

"Using an electron beam is actually not as technologically irrelevant as you might think," she said. "Electron beams are very easy to generate. And yes, things need to be in vacuum, but other than that, people have generated electron beams for nearly 100 years. I'm sure 40 years ago people were saying, 'You're going to put a laser in a disk reader? That's crazy!' But they managed to do it.

"I don't think it's unfeasible to miniaturize electron-beam technology. Humans are good at moving electrons and electricity around. We figured that out a long time ago," Ringe said.

The research should trigger the imaginations of scientists working to create nanoscale machines and processes, she said.

"This is a reconfigurable unit that you can access with light," she said. "Reading something with light is much faster than reading with electrons, so I think this is going to get attention from people who think about dynamic systems and people who think about how to go beyond current nanotechnology. This really opens up a new field."