New materials for the construction of metal-organic two-dimensional quasicrystals

Tiny works of art with great potential

Advertisement

Unlike classical Crystals, quasicrystals do not comprise periodic units, even though they do have a superordinate structure. The formation of the fascinating mosaics that they produce is barely understood. In the context of an international collaborative effort, researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now presented a methodology that allows the production of two-dimensional quasicrystals from metal-organic networks, opening the door to the development of promising new materials.

Physicist Daniel Shechtman merely put down three question marks in his laboratory journal, when he saw the results of his latest experiment one day in 1982. He was looking at a crystalline pattern that was considered impossible at the time. According to the canonical tenet of the day, crystals always had so-called translational symmetry. They comprise a single basic unit, the so-called elemental cell, that is repeated in the exact same form in all spatial directions.

Although Shechtman’s pattern did contain global symmetry, the individual building blocks could not be mapped onto each other merely by translation. The first quasicrystal had been discovered. In spite of partially stark criticism by reputable colleagues, Shechtman stood fast by his new concept and thus revolutionized the scientific understanding of crystals and solid bodies. In 2011 he ultimately received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. To this day, both the basic conditions and mechanisms by which these fascinating structures are formed remain largely shrouded in mystery.

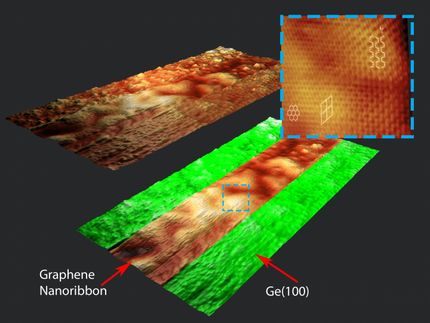

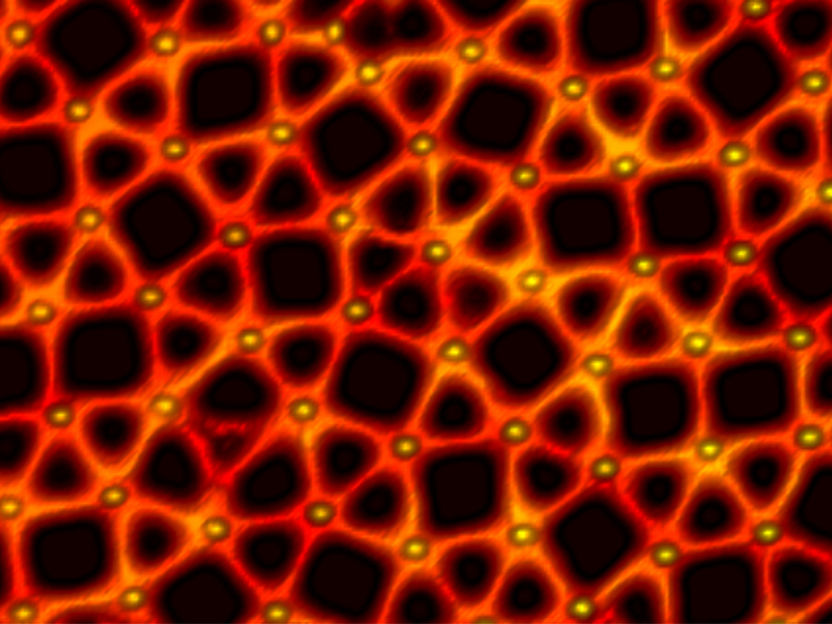

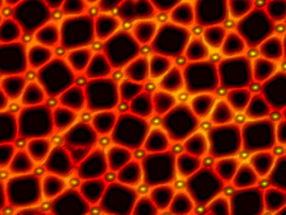

Scanning tunnelling microscopic image of the quasicrystalline network built up with europium atoms linked with para-quaterphenyl–dicarbonitrile

J. I. Urgel / TUM

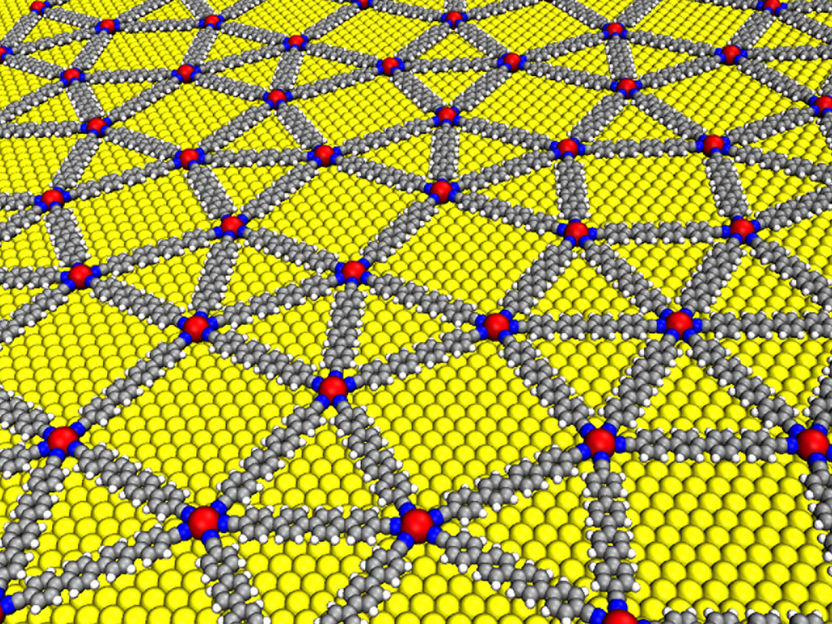

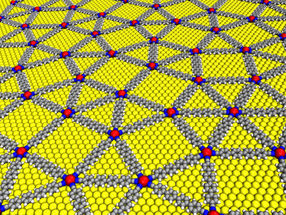

The quasicrystalline network built up with europium atoms linked with para-quaterphenyl–dicarbonitrile on a gold surface (yellow)

Carlos A. Palma / TUM

A toolbox for quasicrystals

Now a group of scientists led by Wilhelm Auwärter and Johannes Barth, both professors in the Department of Surface Physics at TU Munich, in collaboration with Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST, Prof. Nian Lin, et al) and the Spanish research institute IMDEA Nanoscience (Dr. David Ecija), have developed a new basis for producing two-dimensional quasicrystals, which might bring them a good deal closer to understanding these peculiar patterns.

The TUM doctoral candidate José Ignacio Urgel made the pioneering measurements in the course of a research fellowship at HKUST. “We now have a new set of building blocks that we can use to assemble many different new quasicrystalline structures. This diversity allows us to investigate on how quasicrystals are formed,” explain the TUM physicists

The researchers were successful in linking europium – a metal atom in the lanthanide series – with organic compounds, thereby constructing a two-dimensional quasicrystal that even has the potential to be extended into a three-dimensional quasicrystal. To date, scientists have managed to produce many periodic and in part highly complex structures from metal-organic networks, but never a quasicrystal.

The researchers were also able to thoroughly elucidate the new network geometry in unparalleled resolution using a scanning tunnelling microscope. They found a mosaic of four different basic elements comprising triangles and rectangles distributed irregularly on a substrate. Some of these basic elements assembled themselves to regular dodecagons that, however, cannot be mapped onto each other through parallel translation. The result is a complex pattern, a small work of art at the atomic level with dodecagonal symmetry.

Interesting optical and magnetic properties

In their future work, the researchers are planning to vary the interactions between the metal centers and the attached compounds using computer simulation and experiments in order to understand the conditions under which two-dimensional quasicrystals form. This insight could facilitate the future development of new tailored quasicrystalline layers.

These kinds of materials hold great promise. After all, the new metal-organic quasicrystalline networks may have properties that make them interesting in a wide variety of application. “We have discovered a new playing field on which we can not only investigate quasicrystallinity, but also create new functionalities, especially in the fields of optics and magnetism,” says Dr. David Écija of IMDEA Nanoscience.

For one, scientists could one day use the new methodology to create quasicrystalline coatings that influence photons in such a manner that they are transmitted better or that only certain wavelengths can pass through the material.

In addition, the interactions of the lanthanide building blocks in the new quasicrystals could facilitate the development of magnetic systems with very special properties, so-called “frustrated systems”. Here, the individual atoms in a crystalline grid interfere with each other in a manner that prevents grid points from achieving a minimal energy state. The result: exotic magnetic ground states that can be investigated as information stores for future quantum computers.