‘Odd couple’ monolayer semiconductors align to advance optoelectronics

Epitaxy, or growing crystalline film layers that are templated by a crystalline substrate, is a mainstay of manufacturing transistors and semiconductors. If the material in one deposited layer is the same as the material in the next layer, it can be energetically favorable for strong bonds to form between the highly ordered, perfectly matched layers. In contrast, trying to layer dissimilar materials is a great challenge if the crystal lattices don’t match up easily. Then, weak van der Waals forces create attraction but don’t form strong bonds between unlike layers.

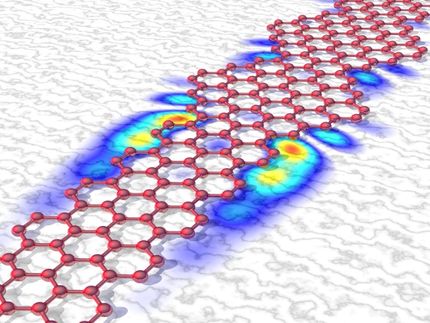

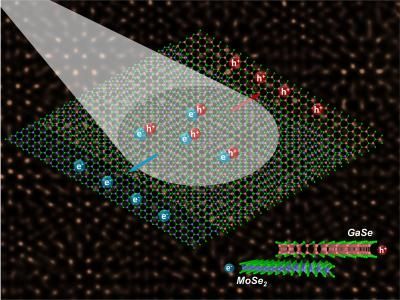

Light drives the migration of charge carriers (electrons and holes) at the juncture between semiconductors with mismatched crystal lattices. These heterostructures hold promise for advancing optoelectronics and exploring new physics. The schematic's background is a scanning transmission electron microscope image showing the bilayer in atomic-scale resolution.

Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Dept. of Energy. Image by Xufan Li and Chris Rouleau

In a study led by the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, scientists synthesized a stack of atomically thin monolayers of two lattice-mismatched semiconductors. One, gallium selenide, is a “p-type” semiconductor, rich in charge carriers called “holes.” The other, molybdenum diselenide, is an “n-type” semiconductor, rich in electron charge carriers. Where the two semiconductor layers met, they formed an atomically sharp heterostructure called a p–n junction, which generated a photovoltaic response by separating electron–hole pairs that were generated by light. The achievement of creating this atomically thin solar cell, published in Science Advances, shows the promise of synthesizing mismatched layers to enable new families of functional two-dimensional (2D) materials.

The idea of stacking different materials on top of each other isn’t new by itself. In fact, it is the basis for most electronic devices in use today. But such stacking usually only works when the individual materials have crystal lattices that are very similar, i.e., they have a good “lattice match.” This is where this research breaks new ground by growing high-quality layers of very different 2D materials, broadening the number of materials that can be combined and thus creating a wider range of potential atomically thin electronic devices.

“Because the two layers had such a large lattice mismatch between them, it’s very unexpected that they would grow on each other in an orderly way,” said ORNL’s Xufan Li, lead author of the study. “But it worked.”

The group was the first to show that monolayers of two different types of metal chalcogenides —binary compounds of sulfur, selenium or tellurium with a more electropositive element or radical—having such different lattice constants can be grown together to form a perfectly aligned stacking bilayer. “It’s a new, potential building block for energy-efficient optoelectronics,” Li said.

Upon characterizing their new bilayer building block, the researchers found that the two mismatched layers had self-assembled into a repeating long-range atomic order that could be directly visualized by the Moiré patterns they showed in the electron microscope. “We were surprised that these patterns aligned perfectly,” Li said.

Researchers in ORNL’s Functional Hybrid Nanomaterials group, led by David Geohegan, conducted the study with partners at Vanderbilt University, the University of Utah and Beijing Computational Science Research Center.

“These new 2D mismatched layered heterostructures open the door to novel building blocks for optoelectronic applications,” said senior author Kai Xiao of ORNL. “They can allow us to study new physics properties which cannot be discovered with other 2D heterostructures with matched lattices. They offer potential for a wide range of physical phenomena ranging from interfacial magnetism, superconductivity and Hofstadter’s butterfly effect.”

Li first grew a monolayer of molybdenum diselenide, and then grew a layer of gallium selenide on top. This technique, called “van der Waals epitaxy,” is named for the weak attractive forces that hold dissimilar layers together. “With van der Waals epitaxy, despite big lattice mismatches, you can still grow another layer on the first,” Li said. Using scanning transmission electron microscopy, the team characterized the atomic structure of the materials and revealed the formation of Moiré patterns.

The scientists plan to conduct future studies to explore how the material aligns during the growth process and how material composition influences properties beyond the photovoltaic response. The research advances efforts to incorporate 2D materials into devices.

For many years, layering different compounds with similar lattice cell sizes has been widely studied. Different elements have been incorporated into the compounds to produce a wide range of physical properties related to superconductivity, magnetism and thermoelectrics. But layering 2D compounds having dissimilar lattice cell sizes is virtually unexplored territory.

“We’ve opened the door to exploring all types of mismatched heterostructures,” Li said.

Original publication

Li, Xufan and Lin, Ming-Wei and Lin, Junhao and Huang, Bing and Puretzky, Alexander A. and Ma, Cheng and Wang, Kai and Zhou, Wu and Pantelides, Sokrates T. and Chi, Miaofang and Kravchenko, Ivan and Fowlkes, Jason and Rouleau, Christopher M. and Geohegan, David B. and Xiao, Kai; "Two-dimensional GaSe/MoSe2 misfit bilayer heterojunctions by van der Waals epitaxy" Science Advances; 2016