Computer Simulation Discloses New Effect of Cavitation

Use for Reducing Wear in Pumps and Plain Bearings

Researchers have discovered a so far unknown formation mechanism of cavitation bubbles by means of a model calculation. In the Science Advances journal, they describe how oil-repellent and oil-attracting surfaces influence a passing oil flow. Depending on the viscosity of the oil, a steam bubble forms in the transition area. This so-called cavitation may damage material of e.g. ship propellers or pumps. However, it may also have a positive effect, as it may keep components at a certain distance and, thus, prevent damage.

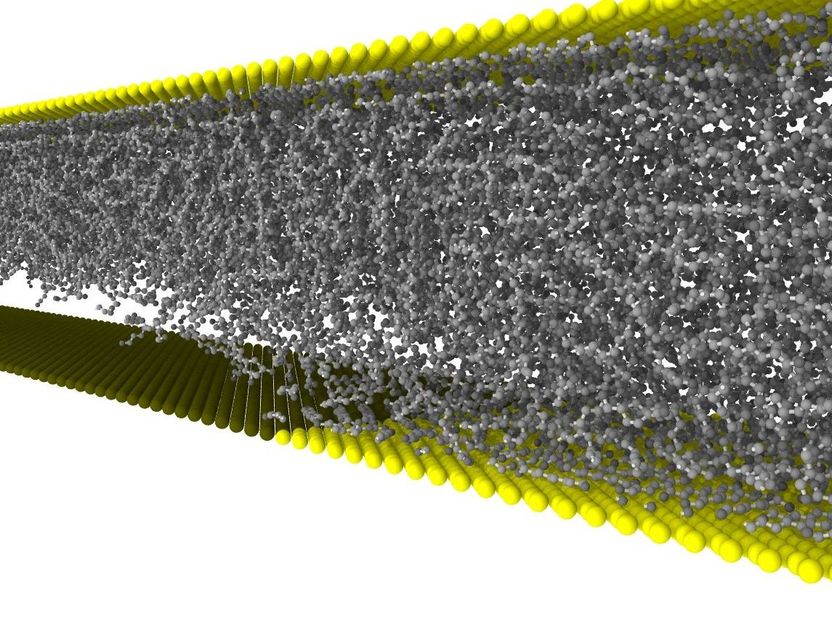

A cavitation bubble is formed in the lubricant between the oil-attracting (yellow) and the oil-repellent surface (black). When used as a buffer, it might reduce wear.

KIT

Materials and friction researchers wanted to know which influence chemically different surfaces have on the flow behavior of a lubricant. In particular, they were interested in flow behavior in nanometer-sized lubrication gaps, a critical case close to boundary friction, i.e. shortly before the surfaces are in direct contact. For this purpose, they generated a mathematical model, in which they varied viscosity of the lubricant and surface properties of the walls. “We were very surprised to find cavitation in the transition area of the surfaces, i.e. at the boundary between oil-attracting and oil-repellent,” Dr. Lars Pastewka and Professor Peter Gumbsch of KIT’s Institute for Applied Materials report.

Cavitation is a known and feared physical phenomenon due to its destructive force. “Existing cavitation models assume a certain geometry that causes cavitation, such as a constriction in a pump or a ship’s propeller producing high flow rates,” Pastewka explains. Here, Bernoulli’s physical law applies, according to which static pressure of a fluid decreases with increasing flow rate. If static pressure drops below the evaporation pressure of the fluid, steam bubbles are formed. If pressure increases again, e.g. if the fluid flow rate decreases after having passed a constriction in a pump, the steam in the bubbles condenses suddenly and they implode. The resulting extreme pressure and temperature peaks lead to typical cavitation craters and significant erosion even of hardened steel.

“This sudden implosion of steam bubbles, however, does not occur in most lubricated tribosystems,” Dr. Daniele Savio says, who has meanwhile taken up work at the Fraunhofer Institute for Mechanics of Materials in Freiburg. “As the fluid gap between two contacting surfaces usually is very narrow, the cavitation bubbles cannot grow and, hence, remain stable. The cavitation bubble then has no destructive effect and even serves as a buffer that reduces wear and friction of the surfaces. It is therefore important to generate this positive effect in a controlled manner,” he adds.

The simulation model of Savio and his colleagues confirms that chemically alternating surfaces may lead to cavitation bubbles. Their publication in Science Advances starts from the question of whether cavitation is the rule or an exception in situations where a lubricant flows between two surfaces. “Usually, surfaces in engines or cylinder systems are never homogeneous, i.e. only oil-attracting or oil-repellent,” Savio points out. “The effect calculated by us may therefore be encountered wherever alternating neighboring surface properties exist in lubricated engines and pumps.”

So far, cavitation has been considered a geometric effect resulting from shear forces, flow rate, and pressure differences exclusively. “It is a completely new finding that cavitation can also occur in transition areas of alternating surface properties,” Pastewka emphasizes. By the specific adjustment of surface chemistry, the researchers are convinced, interaction between surface and lubricant can be improved considerably. In the model simulations, an improved surface separation by 10% was observed.

“A distance increased by 10% means that normal forces and load carrying capacities of plain bearings can be increased,” Savio adds. In any case, surface chemistry has to be re-evaluated as a design element in mechanical engineering, the scientists agree.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Typ CNF / Typ CAM by Hermetic-Pumpen

Reliable pump technology for hazardous applications

Shaft seal-free pumps for maximum reliability and safety

Peristaltic Pumps by AHF analysentechnik

Reliable and Low-pulsation Transport of Liquids in Laboratory Analysis

AZURA Analytical HPLC by KNAUER

Maximize your analytical efficiency with customized HPLC system solutions

Let your application define your analytical system solution

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.