Solar fuels: a refined protective layer for the “artificial leaf”

Advertisement

A team at the HZB Institute for Solar Fuels has developed a process for providing sensitive semiconductors for solar water splitting (“artificial leaves”) with an organic, transparent protective layer. The extremely thin protective layer made of carbon chains is stable, conductive, and covered with catalysing nanoparticles of metal oxides. These accelerate the splitting of water when irradiated by light. The team was able to produce a hybrid silicon-based photoanode structure that evolves oxygen at current densities above 15 mA/cm2.

The “artificial leaf" consists in principle of a solar cell that is combined with further functional layers. These act as electrodes and additionally are coated with catalysts. If the complex system of materials is submerged in water and illuminated, it can decompose water molecules. This causes hydrogen to be generated that stores solar energy in chemical form. However, there are still several problems with the current state of technology. For one thing, sufficient light must reach the solar cell in order to create the voltage for water splitting – despite the additional layers of material. Moreover, the semiconductor materials that the solar cells are generally made of are unable to withstand the typical acidic conditions for very long. For this reason, the artificial leaf needs a stable protective layer that must be simultaneously transparent and conductive.

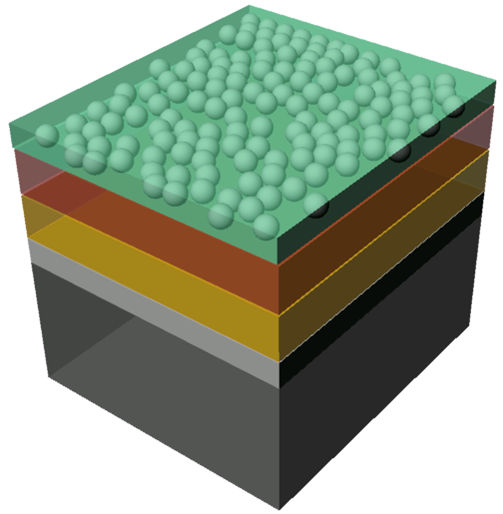

The illustration shows the structure of the sample: n-doped silicon layer (black), a thin silicon oxide layer (gray), an intermediate layer (yellow) and finally the protective layer (brown) to which the catalysing particles are applied. The acidic water is shown in green.

M. Lublow

Catalyst used twice

The team worked with samples of silicon, an n-doped semiconductor material that acts as a simple solar cell to produce a voltage when illuminated. Materials scientist Anahita Azarpira, a doctoral student in Dr. Thomas Schedel-Niedrig’s group, prepared these samples in such a way that carbon-hydrogen chains on the surface of the silicon were formed. “As a next step, I deposited nanoparticles of ruthenium dioxide, a catalyst,” Azarpira explains. This resulted in formation of a conductive and stable polymeric layer only three to four nanometres thick. The reactions in the electrochemical prototype cell were extremely complicated and could only be understood now at HZB.

The ruthenium dioxide particles in this new process were being used twice for the first time. In the first place, they provide for the development of an effective organic protective layer. This enables the process for producing protective layers – normally very complicated – to be greatly simplified. Only then does the catalyst do its “normal job" of accelerating the partitioning of water into oxygen and hydrogen.

Organic protection layer combines excellent stability with high current densities

The silicon electrode protected with this layer achieves current densities in excess of 15 mA/cm2. This indicates that the protection layer shows good electronic conductivity, which is by no means trivial for an organic layer. In addition, the researchers observed no degradation of the cell – the yield remained constant over the entire 24-hour measurement period. It is remarkable that an entirely different material has been favoured as an organic protective layer: graphene. This two-dimensional material has been the subject of much discussion, yet up to now could only be employed for electrochemical processes with limited success, while the protective layer developed at HZB works quite well. Because the novel material could lend itself for the deposition process as well as for other applications, we are trying to acquire international protected property rights”, says Thomas Schedel-Niedrig, head of the group.

Original publication

Anahita Azarpira, Thomas Schedel-Niedrig, H.-J. Lewerenz, Michael Lublow; “Sustained Water Oxidation by Direct Electrosynthesis of Ultrathin Organic Protection Films on Silicon”; Advanced Energy Materials