Experimentation and largest-ever quantum simulation of a disordered system explain quantum many-particle problem

Using some of the largest supercomputers available, physics researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have produced one of the largest simulations ever to help explain one of physics most daunting problems.

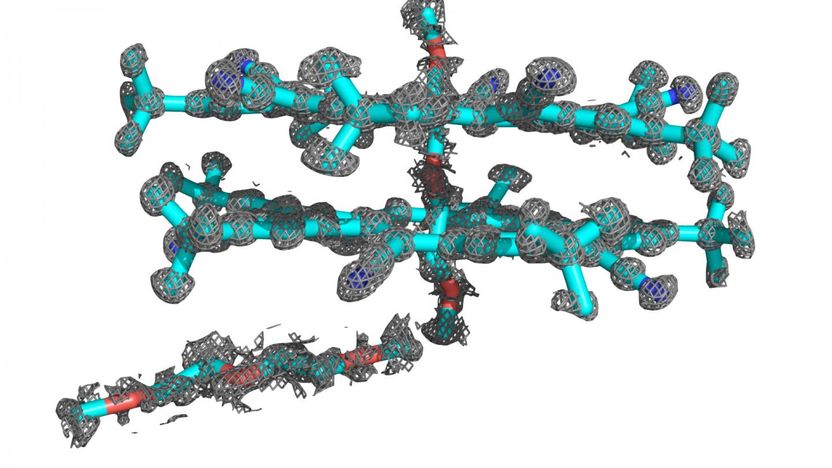

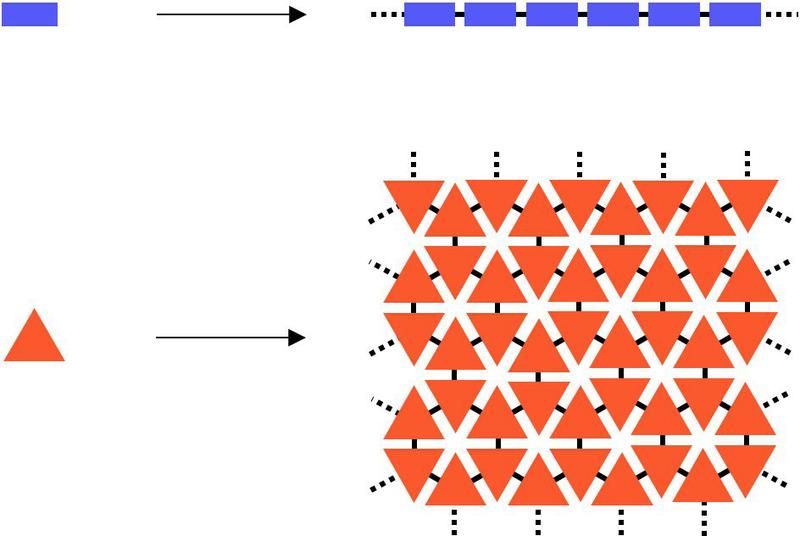

Figure illustrates puddles of localized quasi-condensates found using a quantum Monte Carlo simulation of trapped atoms in a disordered lattice. Individual puddles, consisting of 10-20 particles each, are incoherent relative to each other. The Bose glass is composed of these puddle-like structures.

Ushnish Ray, University of Illinois

"This result was a fantastic collaboration between theory and experiment," explained Physics Professor Brian DeMarco, whose group led the experimental phase of the study. "One of the grandest and most impactful frontiers of physics is the quantum many-particle problem. We do not understand very well what happens when many quantum particles come together and interact with each other. This problem spans some of the largest scales in the universe, like understanding the nuclear matter in neutron stars, to the smallest, such as electron transport in photosynthesis and the quarks and gluons inside a proton."

DeMarco's group experiments with atoms gases cooled to just billionths of a degree above absolute zero temperature in order to experimentally simulate models of materials such as high-temperature superconductors. In these experiments, the atoms play the role of electrons in a material, and the analog of material parameters (like disorder) are completely controlled and known and can be changed every 90-second experimental cycle. Measurements on the atoms are used to expose new physics and test theories.

"In most cases, we lack predictive power, because these problems are not readily computable -- a classical computer requires exponentially costly resources to simulate many quantum systems," added David Ceperley, a professor of physics whose team developed the companion simulation. "A key example of this problem with practical challenges lies with materials such as high-temperature superconductors. Even armed with the chemical composition and structure of these materials, it is almost impossible to predict today at what temperature they will super-conduct."

"A Bose glass is a strange and poorly understood insulator that can occur when disorder is added to a superfluid or superconductor," Carolyn Meldgin from DeMarco's group said. In her experiments, Meldgin was able to use optical disorder to induce a Bose glass, and Ushnish Ray from Ceperley's team exactly simulated the experiment using the Titan supercomputer.

In this work, Ceperley's group achieved the largest scale computer simulations possible of a disordered quantum many-particle system on the biggest supercomputers in existence. These computer simulations were able to simulate relatively large numbers of particles, such as the 30,000 atoms used in DeMarco's experiments.

Together, Meldgin and Ray were able to show something startling--that a dynamic probe in the experiment connects to the equilibrium computer simulations.

"In both cases, the same amount of disorder is required to turn a superfluid into a Bose-glass," Ray stated. "This result is critically important to our understanding of disordered quantum materials, which are ubiquitous, since disorder is difficult to avoid. It also has important implications for quantum annealers, like the D-Wave Systems device."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Intergalactic_space

High_frequency_approximation

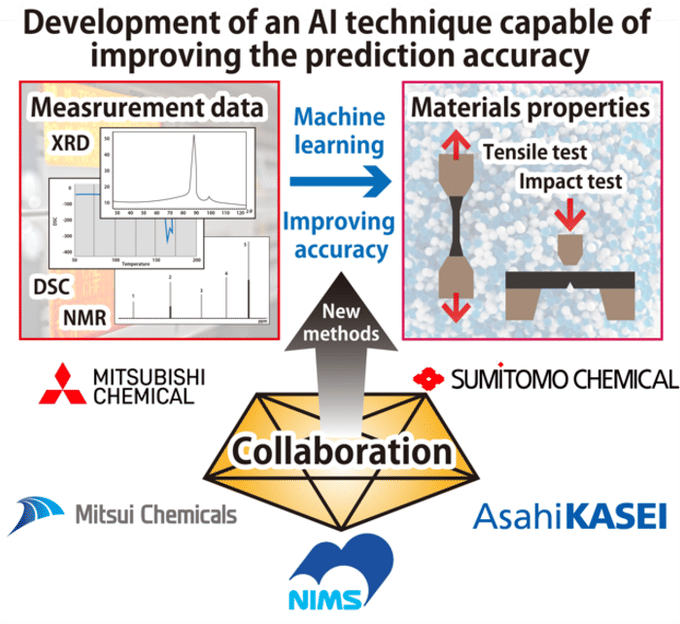

Development of a versatile, accurate AI prediction technique even with a small number of experiments

Randomized_controlled_trial

Maximum_entropy_spectral_analysis

Small-angle_neutron_scattering

Ordered two-dimensional polymers created for the first time