Metamaterial separation proposed for chemical, biomolecular uses

The unique properties of metamaterials have been used to cloak objects from light, and to hide them from vibration, pressure waves and heat. Now, a Georgia Institute of Technology researcher wants to add another use for metamaterials: creating a new directional separation technique that cloaks one compound while concentrating the other.

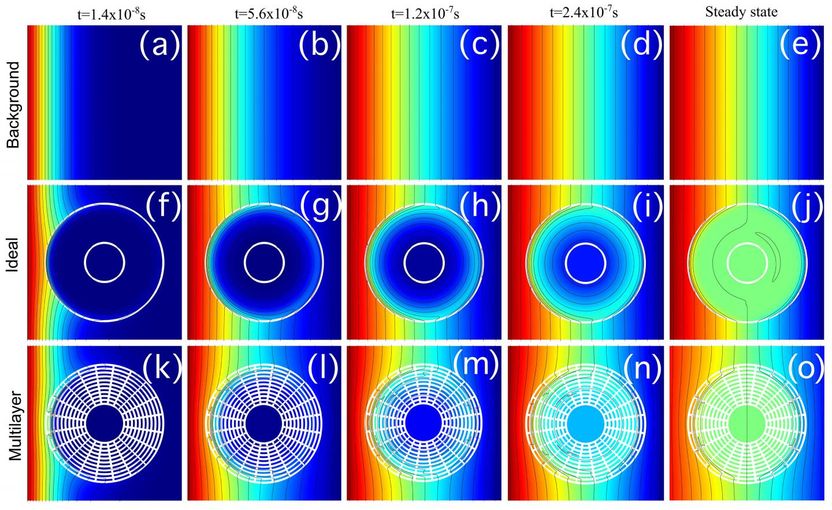

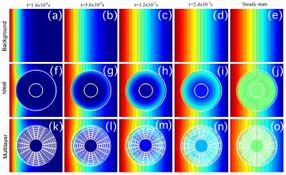

These are concentration profiles for cloaked compound A at different times and steady-state. (a-e) background, (f-j) anisotropic homogeneous cloak, (k-o) multilayer cloak.

Martin Maldovan and Juan Manuel Restrepo-Flórez, Georgia Tech

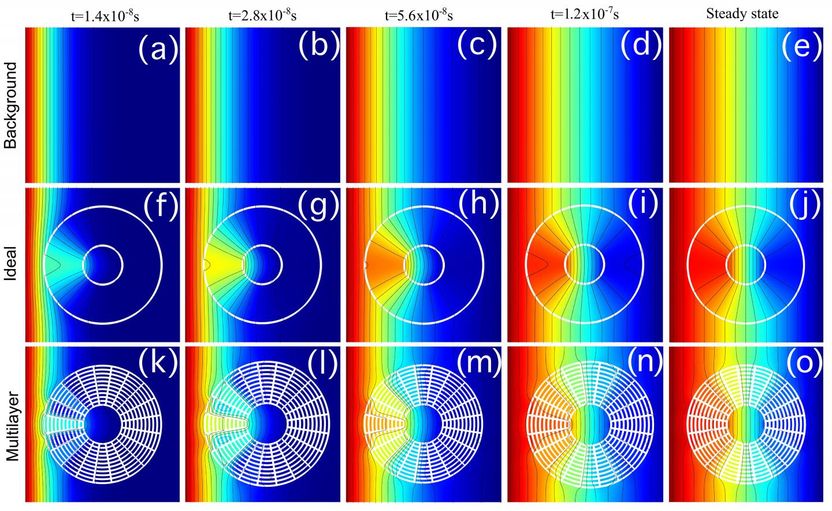

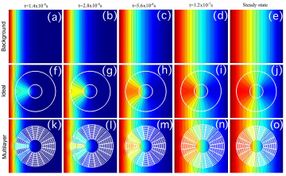

These are concentration profiles for concentrated compound B at different times and steady-state. (a-e) background, (f-j) anisotropic homogeneous concentrator, (k-o) multilayer concentrator.

Martin Maldovan and Juan Manuel Restrepo-Flórez, Georgia Tech

Though the idea must still be proven experimentally, the researchers believe that manipulating mass transfer using metamaterials could help reduce the energy required for certain chemical and biomolecular processes. The proposed technique would use specially-patterned polymeric materials to direct the flow of atoms by taking advantage of their specific physical properties.

A detailed explanation for how the technique could be used to separate a mixture of nitrogen and oxygen - by cloaking the nitrogen and concentrating the oxygen. The research was supported by a seed grant from the American Chemical Society.

"We will control how the atoms cross the metamaterial, in which direction they will go," said Martin Maldovan, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech's School of Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering and School of Physics. "By designing the diffusivity of the metamaterials, we can make the atoms of one compound go one way, and the atoms of another compound go a different way. We are manipulating the physical properties to control the direction the atoms take through the metamaterial shell."

Maldovan and Graduate Research Assistant Juan Manuel Restrepo-Flórez have evaluated their metamaterial using computational techniques, and plan to build a prototype separation device this summer. The work could have applications in such areas as chemical manufacturing, crystal growth of semiconductors, waste recovery of biological solutes or chemicals, and production of artificial kidneys.

The metamaterial technique could supplement traditional membranes, which control the passage of chemicals by varying solubility and diffusivity. Similar in principle to other metamaterials, the mass transfer technique can either direct chemicals around the shell, or concentrate them within the shell.

"Inside the metamaterial shell, you can tell one atom to do one thing, and another atom to do something else," Maldovan said. "Our metamaterials will control the flow because they are anisotropic - certain directions are favored by the structure. We are controlling where the atoms go."

Maldovan's plan for the mass transfer metamaterials uses four different types of polymers, two with high diffusivity and two with low diffusivity. The size and patterning of blocks made from each material is determined by mathematical algorithms.

"With this metamaterial, we can control the direction the atoms can go using the trick of anisotropy," he explained. "This would be in addition to separation based on solubility and diffusivity. We have added an important parameter to the toolbox of chemical engineers: where to send the atoms."

In addition to separating atoms, the ability of the metamaterials to concentrate atoms could allow sensors to detect more dilute quantities, essentially amplifying the available chemical signal.

In their paper, the researchers show how to separate a 50-50 mixture of nitrogen and oxygen using available polymers that have the necessary properties. Each type of separation will require polymers with different properties, not all of which are available in existing materials, meaning not all chemical or biomolecular mixtures will be amenable to separation with the new technique.

The new separation process won't replace traditional distillation and membrane separation processes, but could supplement them, Maldovan said.

"Distillation and evaporation are very energy intensive, but they are the workhorses of the chemical industry," he said. "Membrane processes have been developed to reduce energy use. Our goal is to provide a technique that uses even less energy. This could lead to better and more efficient membranes that would provide better separation."

The metamaterials will ultimately have to be fabricated at the micron scale to be effective. But Maldovan says prototypes can be made using larger structures - at the centimeter scale - to demonstrate the process.

"We need first to fabricate them, then optimize the design," he said. "We know what needs to be fabricated, so future efforts will combine design, fabrication, and optimization."