Microrobots learn from ciliates

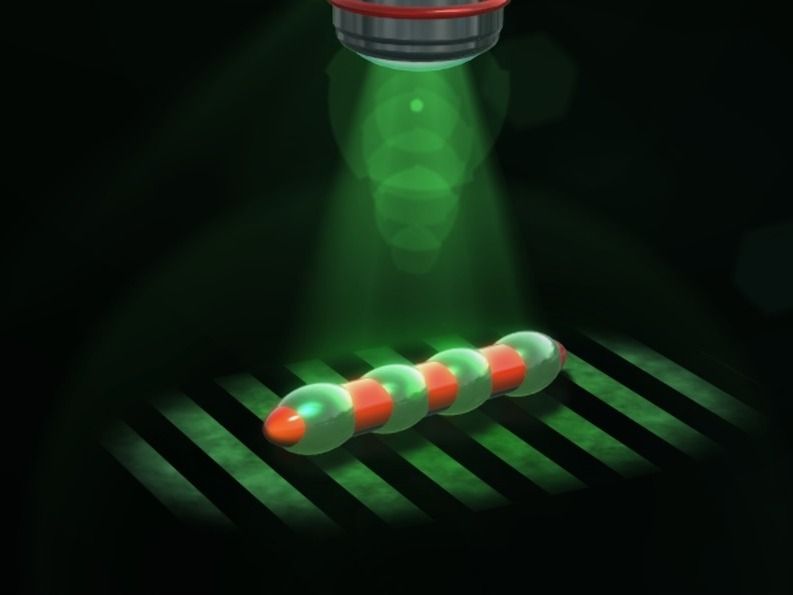

A swimming microrobot formed from liquid-crystal elastomers is driven by a light-induced peristaltic motion

Ciliates can do amazing things: Being so tiny, the water in which they live is like thick honey to these microorganisms. In spite of this, however, they are able to self-propel through water by the synchronized movement of thousands of extremely thin filaments on their outer skin, called cilia. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart are now moving robots that are barely perceptible to the human eye in a similar manner through liquids. For these microswimmers, the scientists are neither employing complex driving elements nor external forces such as magnetic fields. The team of scientists headed by Peer Fischer have built a ciliate-inspired model using a material that combines the properties of liquid crystals and elastic rubbers, rendering the body capable of self-propelling upon exposure to green light. Mini submarines navigating the human body and detecting and curing diseases may still be the stuff of science fiction, but applications for the new development in Stuttgart could see the light-powered materials take the form of tiny medical assistants at the end of an endoscope.

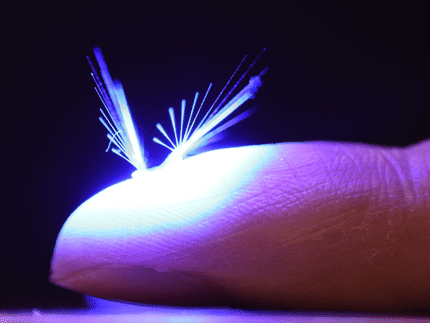

Light-driven microswimmers: the material of the swimming body, which measures just under one millimeter in length, is chosen so that it changes shape when exposed to green light. This causes wave-shaped protrusions to form along the swimmer and drive it in the opposite direction when light patterns move over its surface.

© Alejandro Posada

Their tiny size makes life extremely difficult for swimming microorganisms. As their movement has virtually no momentum, the friction between the water and their outer skin slows them down considerably -- much like trying to swim through thick honey. The viscosity of the medium also prevents the formation of turbulences, something that could transfer the force to the water and thereby drive the swimmer. For this reason, the filaments beat in a coordinated wave-like movement that runs along the entire body of the single-celled organism, similar to the legs of a centipede. These waves move the liquid along with them so that the ciliate -- measuring roughly 100 micrometres, i.e. a tenth of a millimetre, as thick as a human hair -- moves through the liquid.

"Our aim was to imitate this type of movement with a microrobot," says Stefano Palagi, first author of the study at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Stuttgart, which also included collaborating scientists from the Universities of Cambridge, Stuttgart and Florence. Fischer, who is also a Professor for Physical Chemistry at the University of Stuttgart, states that it would be virtually impossible to build a mechanical machine at the length scale of the ciliate that also replicates its movement, as it would need to have hundreds of individual actuators, not to mention their control and energy supply.

Liquid-crystal elastomers behave like Mikado Sticks

Researchers therefore usually circumvent these challenges by exerting external forces directly on the microswimmer: such as a magnetic field that is used to turn a tiny magnetic screw, for example. "This only produces a limited freedom of movement," says Fischer. What the Stuttgart-based researchers wanted to construct, however, was a type of universal swimmer that would be capable of moving freely through a liquid on an independent basis, without external forces being applied and without a pre-defined pace.

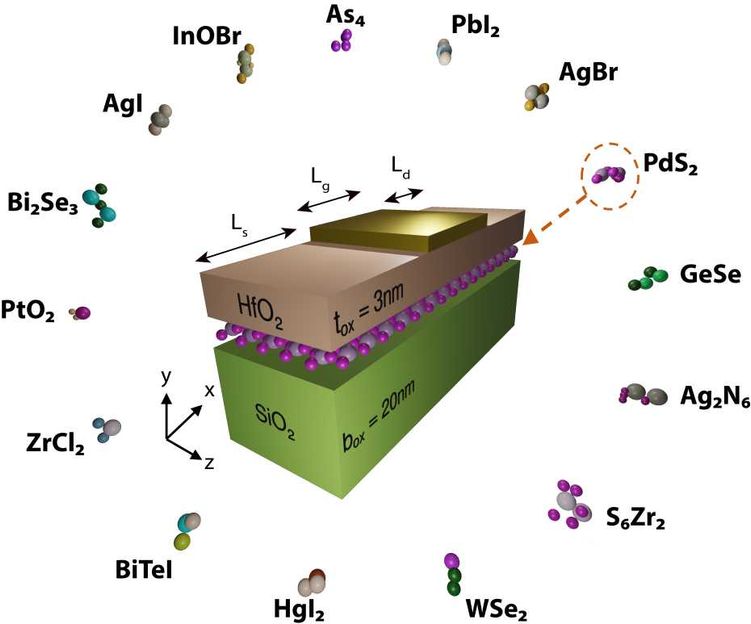

They managed to achieve this with an astonishingly simple method, using so-called liquid-crystal elastomers as the swimming bodies. These change shape when they are exposed to light or heat. Like a liquid crystal, they consist of rod-like molecules that initially have a parallel alignment, similar to a bundle of Mikado Sticks before being thrown by the player. The molecules are connected to one another, which lends the liquid crystal a certain degree of solidity, like a rubber. When heated, the sticks lose their alignment and this causes the material to change its shape, much like the way Mikado Sticks occupy more space on the ground when they are thrown.

The heat was generated by the scientists in Stuttgart in their experiments by exposing the material to green light. The light also causes the shape of the actual molecules themselves to change. These molecules have a chemical bond that acts like a joint. The radiation causes the rod-like molecule at the joint to bend in the shape of a U. This serves to aggravate the molecular disorder, which causes the material to expand even more. The material responds very quickly to the light being switched on and off. When the light it switched off, the material returns immediately to its original shape.

Protrusions follow the light along the swimming body

The researchers produced two types of microrobots: one in the form of an elongated cylinder, roughly one millimetre long and about two hundred micrometres thick, and the other in the form of a tiny disk about 50 micrometres thick and with a diameter of two hundred or four hundred micrometres.

In a first experiment, Fischer's team projected a striped pattern of light onto the cylindrical robot with the aid of a microscope. They observed protrusions forming in the illuminated areas. They then allowed the light pattern to sweep across the cylinder, which prompted the protrusions to also move down along the body like waves. "The movement is generated by the robots from the inside," emphasizes Fischer. The light simply transfers energy to the swimmer, without exerting any force whatsoever. A worm moves along in a similar manner: it creates waves in its body, whereby ring-shaped protrusions and longitudinally aligned elongations run from one end of the worm's body to the other. The specialist term for this is peristalsis.

The peristaltic movement triggered by the light pattern transports liquid along the body of the microswimmer, causing it to move in the opposite direction. In this way, the microrobot reached a speed of about 2.1 micrometres per second and covered a distance of 110 micrometres.

An unknown range of movements for microswimmers

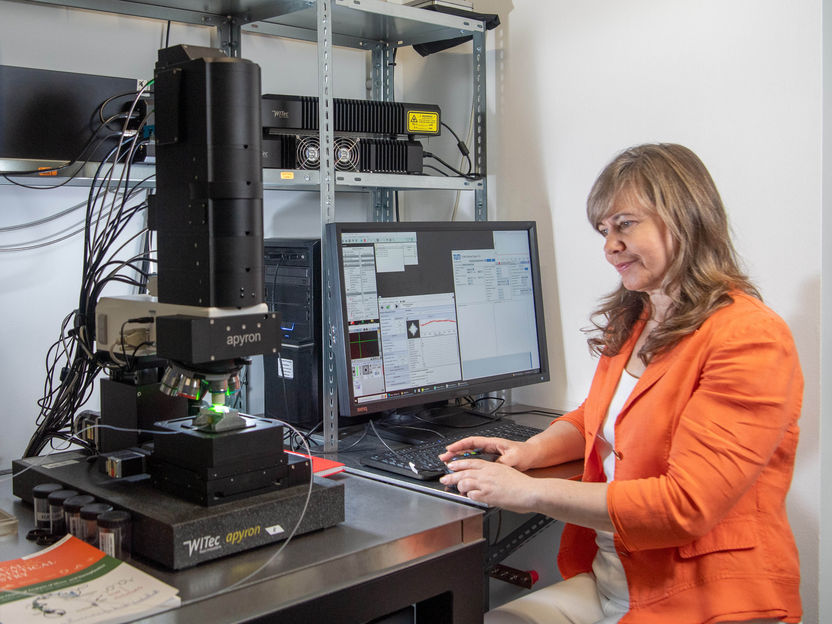

Peer Fischer and his colleagues also demonstrated that they can control the robots with a great degree of flexibility. This is because, in principle, any light pattern can be projected on the swimmers. The researchers generate a pattern using a micromirror device, an array of almost 800,000 tiny mirrors that can be moved individually. In this way, they projected light patterns onto a disk robot and varied the direction so that the microswimmer followed a rectangular trajectory.

They then caused the disk to rotate by projecting a light pattern resembling a fan on to its surface. They even succeeded in controlling two disk robots independently of one another: one turned clockwise, the other counter-clockwise. "This means that a wide range of movements are possible within the very same microrobot, which was previously unheard of in this field," emphasizes Stefano Palagi.

"Another important question was whether our swimmers could be made even smaller," adds co-author Andrew Mark. A theoretical calculation showed that this should be possible: smaller microswimmers could also self-propel using wave-shaped movements. This is the motivation behind the work of the Stuttgart-based researchers: "Our ultimate goal is to imitate as closely as possible the work of nature itself," says Fischer.