A metal that behaves like water

Researchers describe new behaviors of graphene

graphene is going to change the world -- or so we've been told.

In a new paper published in Science, researchers at the Harvard and Raytheon BBN Technology have advanced our understanding of graphene's basic properties, observing for the first time electrons in a metal behaving like a fluid.

Peter Allen/Harvard SEAS

Since its discovery a decade ago, scientists and tech gurus have hailed graphene as the wonder material that could replace silicon in electronics, increase the efficiency of batteries, the durability and conductivity of touch screens and pave the way for cheap thermal electric energy, among many other things.

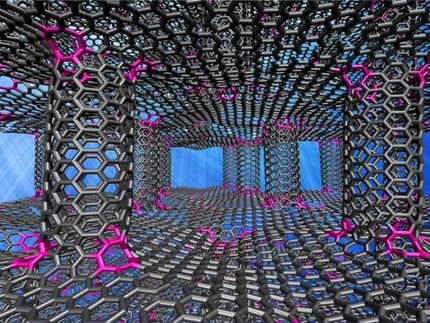

It's one atom thick, stronger than steel, harder than diamond and one of the most conductive materials on earth.

But, several challenges must be overcome before graphene products are brought to market. Scientists are still trying to understand the basic physics of this unique material. Also, it's very challenging to make and even harder to make without impurities.

In a new paper published in Science, researchers at the Harvard and Raytheon BBN Technology have advanced our understanding of graphene's basic properties, observing for the first time electrons in a metal behaving like a fluid.

In order to make this observation, the team improved methods to create ultra-clean graphene and developed a new way measure its thermal conductivity. This research could lead to novel thermoelectric devices as well as provide a model system to explore exotic phenomena like black holes and high-energy plasmas.

This research was led by Philip Kim, professor of physics and applied physics in John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

An electron super highway

In ordinary, three-dimensional metals, electrons hardly interact with each other. But graphene's two-dimensional, honeycomb structure acts like an electron superhighway in which all the particles have to travel in the same lane. The electrons in graphene act like massless relativistic objects, some with positive charge and some with negative charge. They move at incredible speed -- 1/300 of the speed of light -- and have been predicted to collide with each other ten trillion times a second at room temperature. These intense interactions between charge particles have never been observed in an ordinary metal before.

The team created an ultra-clean sample by sandwiching the one-atom thick graphene sheet between tens of layers of an electrically insulating perfect transparent crystal with a similar atomic structure of graphene.

"If you have a material that's one atom thick, it's going to be really affected by its environment," said Jesse Crossno, a graduate student in the Kim Lab and first author of the paper. "If the graphene is on top of something that's rough and disordered, it's going to interfere with how the electrons move. It's really important to create graphene with no interference from its environment."

The technique was developed by Kim and his collaborators at Columbia University before he moved to Harvard in 2014 and now have been perfected in his lab at SEAS.

Next, the team set up a kind of thermal soup of positively charged and negatively charged particles on the surface of the graphene, and observed how those particles flowed as thermal and electric currents.

What they observed flew in the face of everything they knew about metals.

A black hole on a chip

Most of our world -- how water flows (hydrodynamics) or how a curve ball curves -- is described by classical physics. Very small things, like electrons, are described by quantum mechanics while very large and very fast things, like galaxies, are described by relativistic physics, pioneered by Albert Einstein.

Combining these laws of physics is notoriously difficult but there are extreme examples where they overlap. High-energy systems like supernovas and black holes can be described by linking classical theories of hydrodynamics with Einstein's theories of relativity.

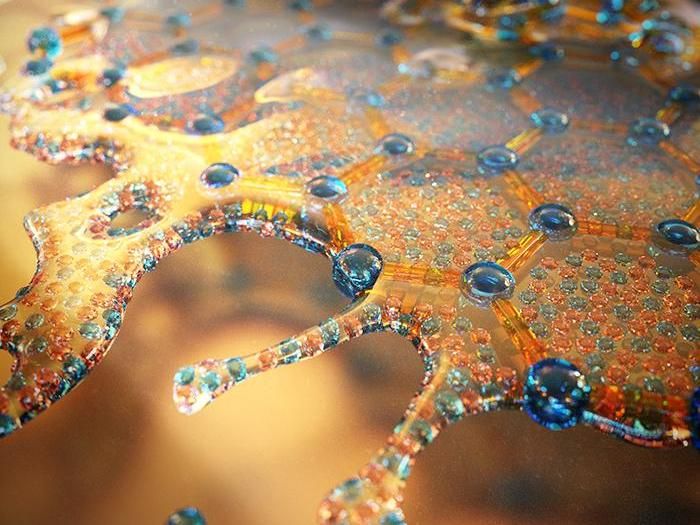

When the strongly interacting particles in graphene were driven by an electric field, they behaved not like individual particles but like a fluid that could be described by hydrodynamics.

"Instead of watching how a single particle was affected by an electric or thermal force, we could see the conserved energy as it flowed across many particles, like a wave through water," said Crossno.

"Physics we discovered by studying black holes and string theory, we're seeing in graphene," said Andrew Lucas, co-author and graduate student with Subir Sachdev, the Herchel Smith Professor of Physics at Harvard. "This is the first model system of relativistic hydrodynamics in a metal."

Moving forward, a small chip of graphene could be used to model the fluid-like behavior of other high-energy systems.

Industrial implications

So we now know that strongly interacting electrons in graphene behave like a liquid -- how does that advance the industrial applications of graphene?

First, in order to observe the hydrodynamic system, the team needed to develop a precise way to measure how well electrons in the system carry heat. It's very difficult to do, said co-PI Dr. Kin Chung Fong, scientist with Raytheon BBN Technology.

Materials conduct heat in two ways: through vibrations in the atomic structure or lattice; and carried by the electrons themselves.

"We needed to find a clever way to ignore the heat transfer from the lattice and focus only on how much heat is carried by the electrons," Fong said.

To do so, the team turned to noise. At finite temperature, the electrons move about randomly: the higher the temperature, the noisier the electrons. By measuring the temperature of the electrons to three decimal points, the team was able to precisely measure the thermal conductivity of the electrons.

"Converting thermal energy into electric currents and vice versa is notoriously hard with ordinary materials," said Lucas. "But in principle, with a clean sample of graphene there may be no limit to how good a device you could make."

Original publication

Crossno, Jesse and Shi, Jing K. and Wang, Ke and Liu, Xiaomeng and Harzheim, Achim and Lucas, Andrew and Sachdev, Subir and Kim, Philip and Taniguchi, Takashi and Watanabe, Kenji and Ohki, Thomas A. and Fong, Kin Chung; "Observation of the Dirac fluid and the breakdown of the Wiedemann-Franz law in graphene"; Science; 2016