Making fuel from thin air

Carbon dioxide captured from air converted directly to methanol fuel for the first time

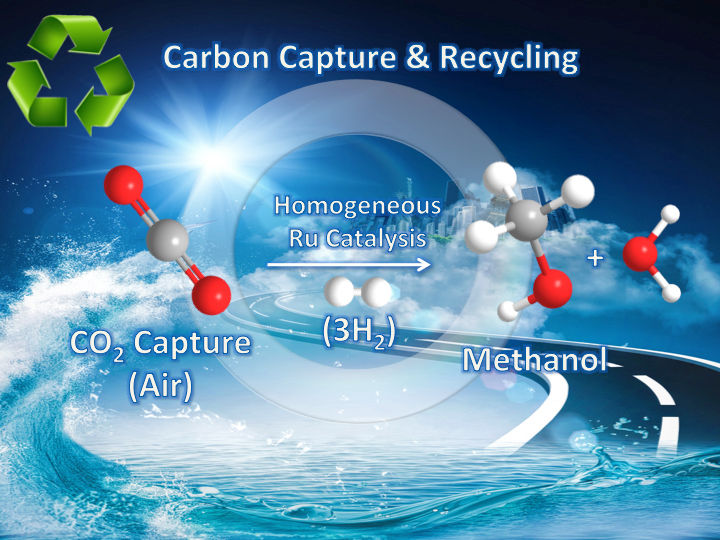

For the first time, researchers there have directly converted carbon dioxide from the air into Methanol at relatively low temperatures.

Artistic description of the process

University of Southern California

The work, led by G.K. Surya Prakash and George Olah of the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, is part of a broader effort to stabilize the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by using renewable energy to transform the greenhouse gas into its combustible cousin - attacking global warming from two angles simultaneously. Methanol is a clean-burning fuel for internal combustion engines, a fuel for fuel cells and a raw material used to produce many petrochemical products.

"We need to learn to manage carbon. That is the future," said Prakash, professor of chemistry and director of the USC Loker Hydrocarbon Research Institute.

The researchers bubbled air through an aqueous solution of pentaethylenehexamine (or PEHA), adding a catalyst to encourage hydrogen to latch onto the CO2 under pressure. They then heated the solution, converting 79 percent of the CO2 captured from air converted directly to methanol fuel for the first time into methanol. Though mixed with water, the resulting methanol can be easily distilled, Prakash said.

Prakash and Olah hope to refine the process to the point that it could be scaled up for industrial use, though that may be five to 10 years away.

"Of course it won't compete with oil today, at around $30 per barrel," Prakash said. "But right now we burn fossilized sunshine. We will run out of oil and gas, but the sun will be there for another five billion years. So we need to be better at taking advantage of it as a resource."

Despite its outsized impact on the environment, the actual concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere is relatively small - roughly 400 parts per million, or 0.04 percent of the total volume, according to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

Previous efforts have required a slower multistage process with the use of high temperatures and high concentrations of CO2, meaning that renewable energy sources would not be able to efficiently power the process, as Olah and Prakash hope.

The new system operates at around 125 to 165 degrees Celsius, minimizing the decomposition of the catalyst - which occurs at 155 degrees Celsius. It also uses a homogeneous catalyst, making it a quicker "one-pot" process. In a lab, the researchers demonstrated that they were able to run the process five times with only minimal loss of the effectiveness of the catalyst.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Speed_of_sound

90_nanometer

“New” LANXESS is developing strongly - LANXESS increases earnings forecast for 2016

Phase-shift_mask

Icicle

Luttinger_liquid

Malvern Instruments and PANalytical to merge

Modern_valence_bond_theory

Controlling zeolite morphologies

Gilbert_N._Lewis