Unconventional superconductivity near absolute zero temperature

Quantum critical point could be the reason for high temperature superconductivity

Advertisement

Researchers at the Goethe University have discovered an important mechanism for superconductivity in a metallic compound containing ytterbium, rhodium and silicon. As reported by Cornelius Krellner and his colleagues the underlying concept of the quantum-critical point has long been discussed as a possible mechanism for high-temperature superconductivity. Confirming this in YbRh2Si2 after 10 years of extensive research is thus a milestone in basic research. Due to its extremely low transition temperature of two-thousandths of a degree above absolute zero, the material will have no practical relevance.

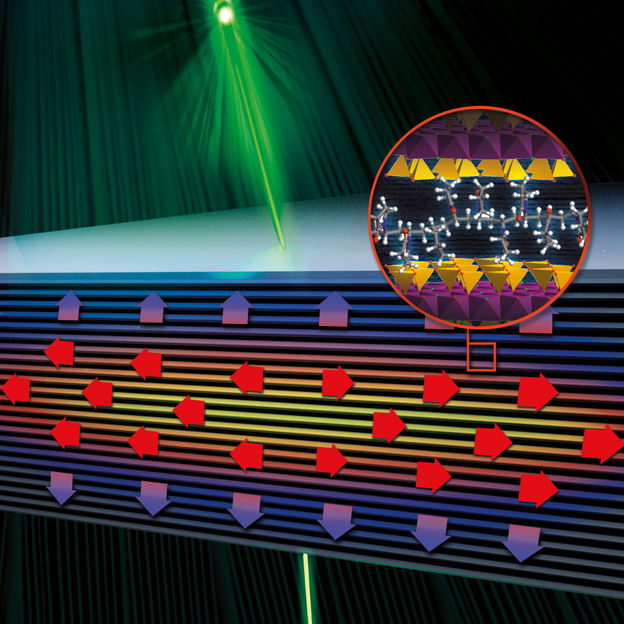

"The ytterbium atoms are essential to the material properties because they are magnetic - and for a particularly fascinating reason", Prof. Krellner from the Institute for Physics at Goethe University explains. This is because the transition to the magnetized state (phase transition) takes place at such low temperatures that temperature-related movements of the tiny atomic magnets no longer play a role. This is what distinguishes this phase transition from all other known transitions, such as the freezing of water into ice. Quantum fluctuations dominate at temperatures near absolute zero (minus 273 degrees Celsius). These are so strong that nature attempts to take on alternative ordered fundamental states.

Superconductivity is a potential collective state which can arise at a quantum-critical point. "After we discovered it in YbRh2Si2, we were able to show that unconventional superconductivity is a general mechanism at a quantum-critical point", Krellner explains. The elaborate low-temperature measurements were taken in collaboration with the Walther-Meißner Institute for Low Temperature Research in Garching.

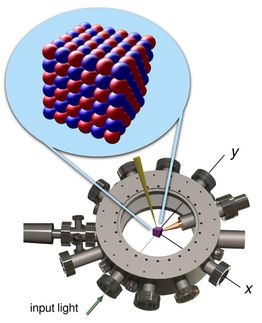

Cornelius Krellner studied YbRh2Si2 10 years ago while working towards his doctorate at the Max-Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids. At the time, he was growing single crystals of the compound. The quality and size of these was essential to measuring the material properties in the first place. "We were all very enthusiastic when we saw the first indications of superconductivity, and I put all my efforts into growing even better and larger single crystals", remembers Krellner, who has headed the Crystal and Materials Laboratory at Goethe University since 2012. That it took so long after that to produce the final proof of unconventional superconductivity was due to the fact that the measurements are extremely time-consuming. Furthermore, it was necessary to study the superconductivity with different techniques in order to show that it really was a case of unconventional superconductivity.

Krellner and his team use a special method to grow the crystals. It prevents ytterbium from vaporizing at the required high temperatures of 1500 degrees Celsius. "We are currently the only ones in Europe with the capability of producing single crystals of YbRh2Si2" Krellner is proud to tell us. Over the next few years, he and his colleagues want to study the magnetic order above the superconducting range. Physicists will also study the superconductivity itself in greater detail over the next few years - a task which will be enabled by the pure and large single crystals from AG Krellner.

Original publication

Schuberth, Erwin and Tippmann, Marc and Steinke, Lucia and Lausberg, Stefan and Steppke, Alexander and Brando, Manuel and Krellner, Cornelius and Geibel, Christoph and Yu, Rong and Si, Qimiao and Steglich, Frank; "Emergence of superconductivity in the canonical heavy-electron metal YbRh2Si2"; Science; 2016