A graphene barrier to precisely control molecules for making nanoelectronics

Scientists from UCLA’s California NanoSystems Institute have found that the same basic approach is an effective way to place molecules in the specific patterns they need within tiny nanoelectronic devices. The technique could be useful in creating sensors that are small enough to record brain signals.

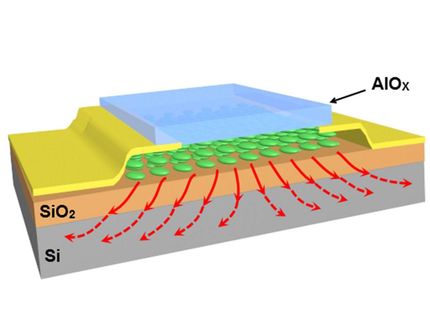

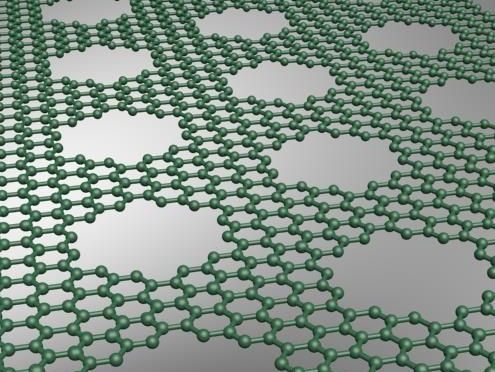

Rendering of a graphene barrier with minuscule holes that allow molecules to attach precisely to a gold substrate exactly where scientists want them.

UCLA California NanoSystems Institute

Led by Paul Weiss, a distinguished professor of chemistry and biochemistry, the researchers developed a sheet of graphene material with minuscule holes in it that they could then place on a gold substrate, a substance well suited for these devices. The holes allow molecules to attach to the gold exactly where the scientists want them, creating patterns that control the physical shape and electronic properties of devices that are 10,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair.

“We wanted to develop a mask to place molecules only where we wanted them on a stencil on the underlying gold substrate,” Weiss said. “We knew how to attach molecules to gold as a first step toward making the patterns we need for the electronic function of nanodevices. But the new step here was preventing the patterning on the gold in places where the graphene was. The exact placement of molecules enables us to determine exact patterning, which is key to our goal of building nanoelectronic devices like biosensors.”

With the advance, making nanoelectronic and nanobioelectronic devices could be much more efficient than current methods of molecular patterning, which use a technique called nanolithography. Weiss said that could be especially useful for scientists who are trying to place molecular sensors on the surface of gold or other nanomaterials that are used for their sensitivity and selectivity but difficult to work with because of their size.

Neurosensors that could measure brain cell and circuit function in real time could reveal new insights into diseases like autism and depression. Ultimately, Weiss said, the researchers hope to be able to stimulate individual brain circuits using sensors so they can predict key chemical differences between function and malfunction in the brain. This knowledge could then be used to develop targets for new generations of treatments for neurological diseases.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.