Technique could set new course for extracting uranium from seawater

Advertisement

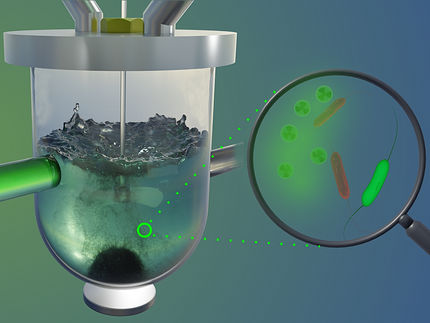

An ultra-high-resolution technique used for the first time to study polymer fibers that trap uranium in seawater may cause researchers to rethink the best methods to harvest this potential fuel for nuclear reactors.

Using high-energy X-rays, researchers discovered uranium is bound by adsorbent fibers in an unanticipated fashion

ORNL

The work of a team led by Carter Abney, a Wigner Fellow at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory, shows that the polymeric adsorbent materials that bind uranium behave nothing like scientists had believed. The results, gained through collaboration with the University of Chicago highlight data made possible with X-ray Absorption Fine Structure spectroscopy performed at the Advanced Photon Source. The APS is a DOE Office of Science User Facility at Argonne National Laboratory.

"Despite the low concentration of uranium and the presence of many other metals extracted from seawater, we were able to investigate the local atomic environment around uranium and better understand how it is bound by the polymer fibers," Abney said.

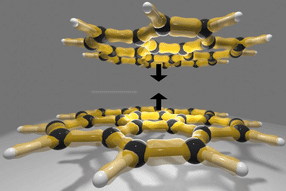

Surprisingly, the spectrum for the seawater-contacted polymer fibers was distinctly different from what was expected based on small molecule and computational investigations. Researchers concluded that for this system the approach of studying small molecule structures and assuming that they accurately represent what happens in a bulk material simply doesn't work.

It is necessary to consider large-scale behavior to obtain the complete picture, highlighting the need for developing greater computational capabilities, according to Abney.

"This challenges the long-held assumption regarding the validity of using simple molecular-scale approaches to determine how these complex adsorbents bind metals," Abney said. "Rather than interacting with just one amidoxime, we determined multiple amidoximes would have to cooperate to bind each uranium molecule and that a second metal that isn't uranium also participates in forming this binding site."

An amidoxime is the chemical group attached to the polymer fiber responsible for binding uranium.

Abney and colleagues plan to use this knowledge to design adsorbents that can harness the vast reserves of uranium dissolved in seawater. The payoff promises to be significant.

"Nuclear power production is anticipated to increase with a growing global population, but estimates predict only 100 years of uranium reserves in terrestrial ores," Abney said. "There is approximately 1,000 times that amount dissolved in the ocean, which would meet global demands for the foreseeable future."