How can engineers make steel that doesn't baulk at hydrogen?

For over 100 years engineers have known that hydrogen can cause metals to become incredibly brittle, but they've been able to do little to protect against it. Now, Oxford University researchers are working on a large collaborative project to build the metals of the future, that can retain their strength in the presence of this disruptive gas.

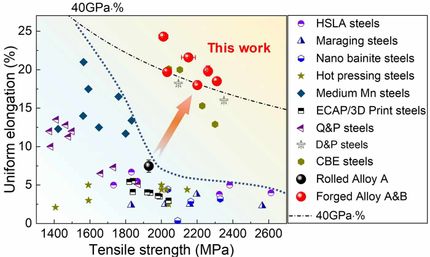

'There are new materials sitting on the shelf that could be used for many kinds of applications – construction, aerospace, cars, all sorts,' explains Professor Alan Cocks from the University's Department of Engineering Science . 'But companies are afraid to use some of them because of their susceptibility to what's known as hydrogen embrittlement.' First observed before the turn of the 20th century, hydrogen embrittlement is a phenomenon where some materials – particularly steel, but also metals like zirconium and titanium – become far weaker when exposed to hydrogen.

Professor Cocks points out that some steels can suffer a decrease in strength by as much as a factor of 10 when they're exposed to hydrogen, which means that they could fail when subjected to just a tenth of the maximum stress they can usually withstand. If engineers could find a way to overcome this weakness, they could more confidently use some materials – predominantly steels, but also the likes of titanium for aerospace applications or the zirconium sheathing of nuclear power rods.

'It seems like it should be a straightforward problem to solve,' explains Professor Cocks. 'But there's immense controversy about why it happens, and despite lots of experimental studies and theoretical modelling there's still no real solution.' That's why researchers from Oxford University are working on a large collaborative project – along with Cambridge University, Imperial College London, King's College London and the University of Sheffield – to finally understand its causes and build new materials that overcome them.

To make progress, the researchers decided to put together a team that understood metals from the atom up. So the team includes Oxford scientists from the Department of Materials, who investigate how materials work at the atomic level, and from the Department of Engineering Science, who model the larger-scale properties of the materials and the ways that hydrogen can move through the metallic structure. Elsewhere around the UK there are teams that specialise in different aspects of modelling, as well as the design, fabrication and testing of new metals.

Just over a year into the project, the Oxford team are trying to understand exactly how hydrogen causes steel to become brittle. There are, broadly speaking, two competing schools of thought. The first suggests that the hydrogen atoms build up around tiny defects called dislocations in the metal's crystal structure, affecting the way the material irrevocably deforms. The second proposes that instead the hydrogen gathers at boundaries between chunks of metallic crystal known as grains, making it easier to pull them apart. 'We suspect it could be a combination of both,' admits Professor Cocks. 'But by modelling the process at different scales, we hope to find out once and for all.'

At the same time, the Oxford engineers are also proposing new ways to help steels cope in the presence of hydrogen. 'In the past, people have used coatings to protect against hydrogen being absorbed by metals,' points out Professor Cocks. 'But if you get a crack in that coating, you expose the material underneath. And anyway, because of its size, hydrogen can ultimately diffuse through any material, so a coating will only ever slow down the process.'

Instead, the team is seeking to develop a series of internal traps that can capture the hydrogen as it enters the metal. 'You can think of them as little sponges in the steel that mop up all the hydrogen so that it's not detrimental to the material properties,' explains Professor Cocks. So far the team has been studying how carbides – a type of carbon-metal compound – can be used within the microstructure of metals to such ends, because hydrogen appears to gravitate towards boundaries between them and grains of iron. The team hope that once they move to this boundary, the hydrogen will sit there benignly.

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Tolerability Demonstrated by ABX-EGF as Monotherapy in Advanced Cancers

Bioswale

Golden_beryl

HLA-Cw*16

BASF temporarily idles steam cracker in Ludwigshafen - Order levels remain generally low

Actinometer

Tiger's_eye

Cytarabine

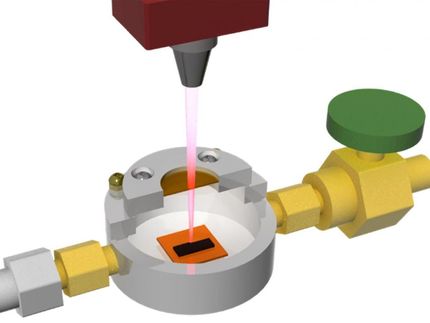

Detecting fake wine vintages: It's an (atomic) blast

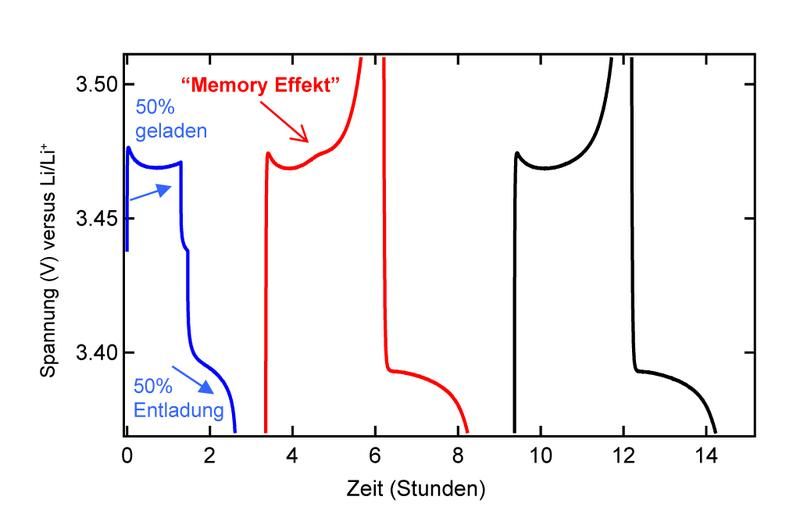

Memory effect now also found in lithium-ion batteries

Sigmatropic_reaction