Physicists measure force that makes antimatter stick together

Advertisement

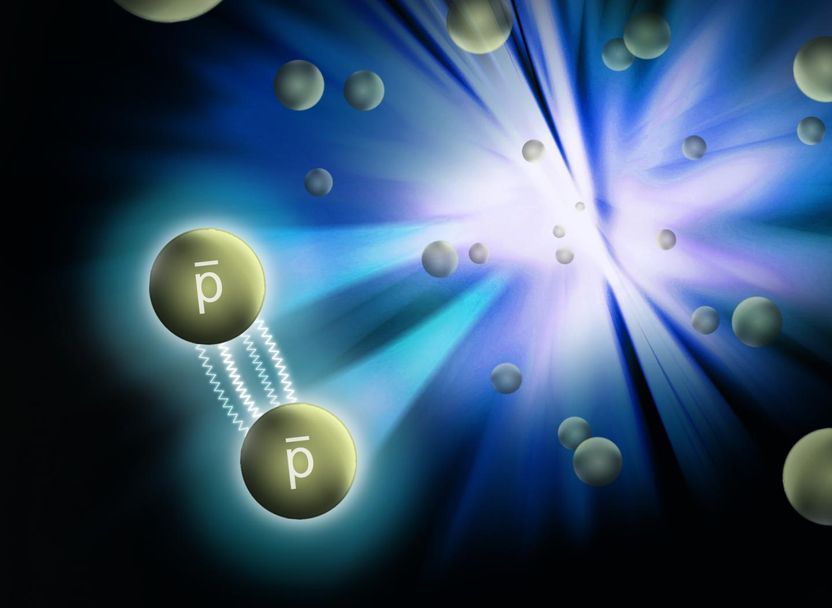

Peering at the debris from particle collisions that recreate the conditions of the very early universe, scientists have for the first time measured the force of interaction between pairs of antiprotons. Like the force that holds ordinary protons together within the nuclei of atoms, the force between antiprotons is attractive and strong.

A new measurement by RHIC's STAR collaboration reveals that the force between antiprotons (p with bar above it) is attractive and strong--just like the force that holds ordinary protons together within the nuclei of atoms.

Brookhaven National Laboratory

The experiments were conducted at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider and may also help scientists explore one of science's biggest questions: why the universe today consists mainly of ordinary matter with virtually no antimatter to be found.

"The Big Bang-the beginning of the universe-produced matter and antimatter in equal amounts. But that's not the world we see today. Antimatter is extremely rare. It's a huge mystery!" said Aihong Tang, a Brookhaven physicist involved in the analysis, which used data collected by RHIC's STAR detector. "Although this puzzle has been known for decades and little clues have emerged, it remains one of the big challenges of science. Anything we learn about the nature of antimatter can potentially contribute to solving this puzzle."

"We are taking advantage of the ability to produce ample amounts of antimatter so we can conduct this study," said Tang.

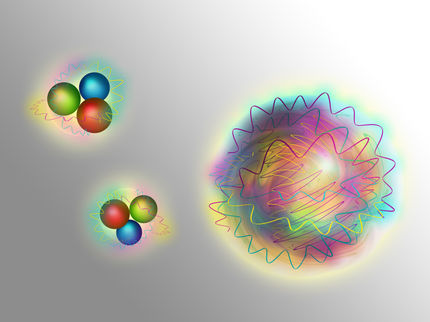

The STAR collaboration has previous experience detecting and studying rare forms of antimatter-including anti-alpha particles, the largest antimatter nuclei ever created in a laboratory, each made of two antiprotons and two antineutrons. Those experiments gave them some insight into how the antiprotons interact within these larger composite objects. But in that case, "the force between the antiprotons is a convolution of the interactions with all the other particles," Tang said. "We wanted to study the simple interaction of unbound antiprotons to get a 'cleaner' view of this force."

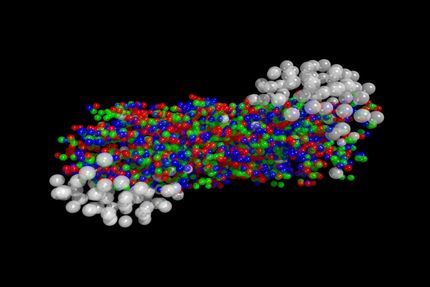

To do that, they searched the STAR data from gold-gold collisions for pairs of antiprotons that were close enough to interact as they emerged from the fireball of the original collision.

"We see lots of protons, the basic building blocks of conventional atoms, coming out, and we see almost equal numbers of antiprotons," said Zhengqiao Zhang, a graduate student in Professor Yu-Gang Ma's group from the Shanghai Institute of Applied Physics of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who works under the guidance of Tang when at Brookhaven. "The antiprotons look just like familiar protons, but because they are antimatter, they have a negative charge instead of positive, so they curve the opposite way in the magnetic field of the detector."

"By looking at those that strike near one another on the detector, we can measure correlations in certain properties that give us insight into the force between pairs of antiprotons, including its strength and the range over which it acts," he added.

The scientists found that the force between antiproton pairs is attractive, just like the strong nuclear force that holds ordinary atoms together. Considering they'd already discovered bound states of antiprotons and antineutrons-those antimatter nuclei-this wasn't all that surprising. When the antiprotons are close together, the strong force interaction overcomes the tendency of the like (negatively) charged particles to repel one another in the same way it allows positively charged protons to bind to one another within the nuclei of ordinary atoms.

In fact, the measurements show no difference between matter and antimatter in the way the strong force behaves. That is, within the accuracy of these measurements, matter and antimatter appear to be perfectly symmetric. That means, at least with the precision the scientists were able to achieve, there doesn't appear to be some asymmetric quirk of the strong force that can account for the continuing existence of matter in the universe and the scarcity of antimatter today.