Playing billiard with hybrid light and matter particles

Advertisement

For the first time, physicists from the University of Würzburg have successfully modelled and studied a particularly chaotic system in quantum nature. The work by Professor Sven Höfling and Christian Schneider is part of an international project.

The experiment starts from the principle of a classic billiard table. An international team of physicists created a kind of miniature pool table where the balls are replaced by quantum particles. In reality, the "table" is a small chip manufactured in the Würzburg-based Gottfried-Landwehr Laboratory for Nanotechnology. The table's bumpers, however, are not made of exquisite wood, but are defined by light instead.

The Australian co-authors of the research use a special mirror and grid configuration to form a laser beam into billiard shape. Excited by laser, light-matter hybrids are generated on the table and propagate in the system. "They have the property of flowing away from the position where the light pulse hits the chip," Schneider explains. These polaritons form a link at the boundary of light and matter. "This results in hybrid states that can be accessed relatively easily from the outside. A pure light system is more difficult to influence from the outside," the scientist further.

A "round corner" adds chaos to the system

What is special about the billiard table: One corner has a round bulge. "If the billiard ball does not have its own spin, the incident angle when bouncing off a normal bumper is equivalent to the angle of reflection. The ball's course is completely predictable, even if you hit it very hard," says Christian Schneider. With a "round corner" this is no longer true. It makes the movement of the billiard ball (the polariton) unpredictable. Once the ball hits this area, it can bounce off in any angle. This has been impossible to model with hybrid particles in quantum nature so far.

"It is crucial to find out what happens when there are imperfections in a quantum system," Schneider continues. Because in quantum structures, too, physicists ultimately want to "send a piece of information from A to B". In the remote future, this could be among others the basis of new ways of transmitting or storing data. It is hence crucial to find out what misdirects the information. "Such a game of billiard shows us what will happen." By creating the billiard model the researchers have thus established a "relatively simple" method to model such chaotic effects.

Material from the Würzburg-based Gottfried-Landwehr Laboratory

Moreover, the fundamental study of a chaotic system is also of interest for other physicists. "A quantum model always behaves differently from a classic system. If you are capable of modelling and selectively manipulating this chaotic billiard in the quantum system, this might yield a better understanding of chaos and movement of the hybrid particles at the quantum level," Schneider goes on.

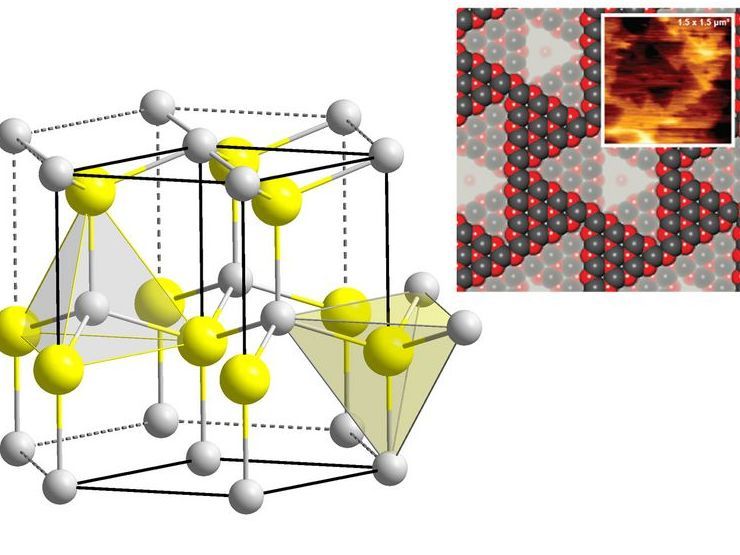

The base material for the billiard table is a semiconductor multilayer concept. Where similar tests used microwaves, for example, the miniaturisation relied on one of the strong sides of the Würzburg Physics Department. "We are at the scale of 1 to 10 microns here," says Professor Sven Höfling, Head of the Department of Technical Physics. 1 micron equals 0.001 centimetres.

Additionally, the chip can be used in the future to conduct further research relatively easily: "The chip we created shows the physics. Now you can apply light from the outside and configure it to your needs," Höfling says and he adds: "The hardware can remain unchanged and in principle you can apply any form you like."

Comparably simple detection of the decaying particles

Another important factor in the test: The researchers created a non-Hermitian system. "Imagine it like this: The bumper of the system is not infinitely high, the ball may even fly beyond the table – which increases the complexity considerably," says Höfling. They succeeded in modelling and studying very complex physics in the experiment.

After a while, the hybrid particles decay. Then they are relatively easy to detect: "All you need is a camera with a spectrometer," says Christian Schneider.

In a next step, the Würzburg scientists are seeking to straighten out the chaos and put the observed effects to use. "We are interested in how far we can push this," says Schneider and mentions the possibility to build logic circuits based on the movement of the hybrid particles.