Designed defects in liquid crystals can guide construction of nanomaterials

Advertisement

Imperfections running through liquid crystals can be used as miniscule tubing, channeling molecules into specific positions to form new materials and nanoscale structures, according to engineers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The discovery could have applications in fields as diverse as electronics and medicine.

"By controlling the geometry of the system, we can send these channels from any one point to any other point," says Nicholas Abbott, a UW-Madison professor of chemical and biological engineering. "It's quite a versatile approach."

So far, Abbott and his collaborators at UW-Madison's Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC) have been able to assemble phospholipids - molecules that can organize into layers in the walls of living cells - within liquid crystal defects.

Their technique may also be useful for assembling metallic wires and various semiconducting structures vital to electronics. There's also potential for mimicking the selective abilities of a membrane, designing a defect so that one type of molecule can pass through while others can't.

"This is an enabling discovery," Abbott says. "We're not looking for a specific application, but we're showing a versatile method of fabrication that can lead to structures you can't make any other way."

The researchers - including UW-Madison graduate students Xiaoguang Wang, Daniel S. Miller and Emre Bukusoglu, and Juan J. de Pablo, a former UW-Madison engineering professor now at the University of Chicago - published details of their advance in Nature Materials.

For about 20 years, Abbott's research has examined the surfaces of soft materials, including liquid crystals -- a particular phase of matter in which liquid-like materials also exhibit some of the molecular organization of solids.

"We've done a lot of work in the past at the interfaces of liquid crystals, but we're now looking inside the liquid crystal," he says. "We're looking at how to use the internal structure of liquid crystals to direct the organization of molecules. There's no prior example of using a defect in a liquid crystal to template molecular organization."

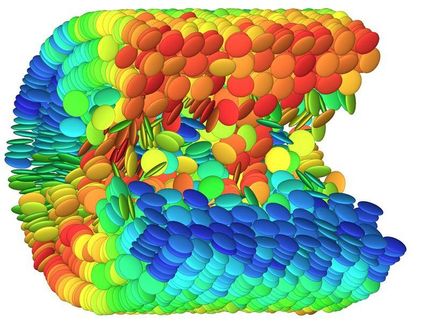

When the researchers manipulate the geometry of a liquid crystalline system, a variety of different defects can result. Abbott's group assembled liquid crystals with defects shaped like ropes or lines they call "disclinations," that formed templates they could fill with amphiphilic (water- and fat-loving) molecules.

Then they can link together assemblies of molecules and remove the liquid crystal templates, leaving behind the amphiphilic building blocks in a lasting, nanoscale structure.

The research is an example of how liquid crystal research is taking us from the nano to macro world, says Dan Finotello, program director at the National Science Foundation, which funds the MRSEC.

"It is also an exquisite demonstration of MRSEC programs' high impact," Finotello says. "MRSECs bring together several researchers of varied experience and complementary expertise who are then able to advance science at a considerably faster rate."