Fast charging cycles make batteries age more quickly

X-ray study images structural damage in lithium-ion batteries

Charging lithium-ion batteries too quickly can permanently reduce the battery capacity. Portions of the energy storage structure are thereby destroyed and deactivated. These structural changes have been visualized for the first time by DESY researcher Dr. Ulrike Bösenberg along with her team at DESY's X-ray source PETRA III. Their fluorescence studies show that even after only a few charging cycles, damage to the inner structure of the battery material is clearly evident, damage which takes longer to arise during slower charging. The results of the studies will be published in the latest edition of the academic journal Chemistry of Materials (published online in advance).

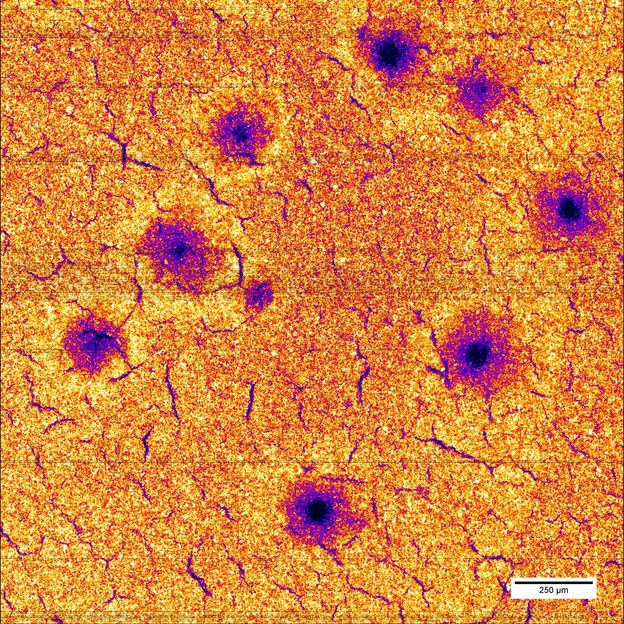

After 25 fast charging cycles, the manganese distribution in the electrode shows large holes.

Ulrike Bösenberg/DESY

Lithium-ion batteries are very common because they possess a high charge density. Typically the storage capacity is significantly diminished after one thousand charges and discharges. A promising candidate for a new generation of such energy storage systems, particularly due to their high voltage of 4.7 Volts, are what are known as lithium-nickel-manganese-oxide spinel materials or LNMO spinels. The electrodes consist of miniature crystals, also referred to as crystallites, which are connected with binder material and conductive carbon to form the thin layer.

The team around Bösenberg, which also includes researchers from the University of Giessen, University of Hamburg and from Australia's national science agency CSIRO, studied the negative electrodes of this LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 compound at PETRA III's X-ray microfocus beamline P06. They could determine, with half a micrometre (millionth of a meter) resolution, the precise distribution of nickel and manganese over large areas on the electrode by utilising a novel X-ray fluorescence detector. The molecular structure of the active material in the battery electrodes is composed of nickel (Ni), manganese (Mn) and oxygen (O) – where the structure is a relatively rigid crystal lattice into which the lithium ions, as mobile charge carriers, can be inserted or extracted.

In their present study, the researchers exposed different battery electrodes to twenty-five charging and discharging cycles each, at three different rates and measured the elementary distribution of the electrode components. The scientists could show that during fast charging, manganese and nickel atoms are leached from the crystal structure. In their investigation, the researchers spotted defects such as holes in the electrode with up to 100 microns (0.1 millimetre) diameter. The destroyed areas can no longer be utilized for lithium storage.

Utilizing the X-ray fluorescence method in their studies, the researchers took advantage of the fact that X-rays can excite chemical elements into fluorescence, a short-term radiation emission. The wavelength or energy of the fluorescent radiation is a characteristic fingerprint for each chemical element. This way, the distribution of the individual materials in the electrode can be precisely determined. For this task, the researchers used a novel fluorescence detector, only two of which currently exist worldwide in this form. This Maia detector, a joint development by CSIRO and Brookhaven National Laboratory in the US, consists of nearly four hundred individual elements that collect the sample’s fluorescent radiation. Due to the detector’s high energy resolution and sensitivity, it is capable of localizing several chemical elements simultaneously.

The narrow and high-intensity PETRA III X-ray beam could precisely scan the sample surface, which measured approximately 2x2 square millimetres, with a resolution of half a micrometre. Investigating each point took merely a thousandth of a second. “It is the first time that we could localize these inhomogeneities with such a high spatial resolution over so large an area,” says Bösenberg. “We hope to better understand the effects and to create the foundation for improved energy storage devices.”

What is still puzzling is where the dissolved nickel and manganese atoms end up –this is a question the researchers would like to resolve in further studies. “There are indications that the dissolved material, at least partially, settles on the anode, which inflicts twice the damage to the battery properties,” Bösenberg summarizes.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Battery Technology

The topic world Battery Technology combines relevant knowledge in a unique way. Here you will find everything about suppliers and their products, webinars, white papers, catalogs and brochures.

Topic World Battery Technology

The topic world Battery Technology combines relevant knowledge in a unique way. Here you will find everything about suppliers and their products, webinars, white papers, catalogs and brochures.