Better catalysts, made-to-order

Scientists have taken a big step toward the rational design of catalysts

Advertisement

Most of our food, medicine, fuel, plastics and synthetic fibers wouldn't exist without catalysts, materials that open favorable pathways for chemical reactions to run forth. And yet chemists don't fully understand how most catalysts work, and developing new catalysts often still depends on laborious trial-and-error.

But in a new study appearing in the journal Science, University of Utah chemists captured enough data on the crucial steps in a reaction to accurately predict the structures of the most efficient catalysts, those that would speed the process with the least amount of unwanted byproducts.

"We can pretty much predict the performance of any catalyst and substrate within this reaction space," says senior author Matthew Sigman, a professor of chemistry at the University of Utah.

The new approach could help chemists design catalysts that are not just incrementally better, but entirely new, Sigman says. With a clearer understanding of the forces at play as molecules cling and shape-shift together, chemists might be able to take advantage of interactions now regarded as unimportant or impossible to control.

"Now we can go in and find out what is important to us, which is why things work," says postdoctoral researcher Anat Milo, the study's first author. "That is going to be absolutely essential for developing next-generation catalysts." Milo and Sigman conducted the research with Andrew Neel and F. Dean Toste of the University of California at Berkeley.

High value targets

It's hard to overstate the value of catalysts. By one estimate, over a third of global economic output depends on catalytic processes. Efforts to reduce the waste stream from chemical manufacturing hinge on the invention of better catalysts, as do renewable energy technologies such as fuel cells and artificial photosynthesis.

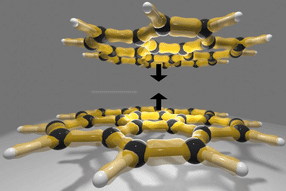

In the new study, the researchers focused on a reaction for modifying a carbon-ring structure found in many compounds with potent pharmaceutical effects (1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline and its derivatives). They chose this reaction because of its practical importance, but also because it is a complicated reaction not amenable to probing by standard techniques.

"There is so little understood about these reactions that design is very difficult," Sigman says.

The trickiest part is steering the reaction to produce structures with the desired "handedness." Carbon-based compounds can assemble into forms that are mirror images, or enantiomers. They have all of the same atoms, but the spatial arrangement of the atoms changes the three-dimensional structure. The forms differ much like a person's left and right hands. Typically only one of the forms will have the desired chemical activity. "You can imagine it as a hand-shake between a molecule and its target," says Milo. "You cannot shake with the wrong hand."

A perfect catalyst would drive the reaction to produce only the desired mirror-image form. None of the starting material would be wasted on synthesis of the inactive enantiomer. The researchers sought to isolate the crucial interactions that tip the reaction toward producing one form or the other of the end product.

To gain insight, the researchers generated a set of catalysts with systematic changes in structure. At certain positions on the molecule, they substituted a series of different atoms or groups of atoms to alter its size or electronic properties. They did the same to generate a set of the chemical substrates that the catalyst acts upon.

Going big with data

Experimenting with these sets allowed the researchers to measure how selectively a given catalyst worked to produce the desired product. The experiments generated a large set of measurements, from poor to high selectivity. Significantly, the researchers didn't discard any results, even those from reactions with terrible selectivity.

"It is the premise of big data," Sigman says. "There are no 'bad' results. Every result is important because it is telling you something."

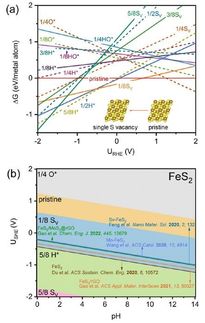

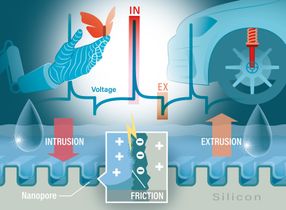

The researchers used the data to perform a statistical analysis to identify the structural features of a catalyst and its substrate that correlated most clearly with reaction selectivity. And based on these correlations, they developed a computational model to predict outcomes.

Additional experiments with 20 different catalyst-substrate pairs showed that the model could accurately predict selectivity. "One catalyst afforded the cleanest reaction observed to date," Sigman says. "The least amount of byproducts was formed - a result that was accurately predicted by the data-intensive model developed to describe this reaction."

To keep track of the large and intricate datasets, the researchers had to devise a way to visualize all of the relevant information. In one instance, they plotted each catalyst's selectivity as it varied with different substrates. They arranged these plots according to which positions on the molecules were modified. The systematic display of the data helped uncover informative patterns in the ways that features with varying geometry and electronic properties behave during a reaction.

"That was the most fun part," says Milo. "Looking at it with the eyes of a synthetic chemist to try to see from all of these trends and patterns something that could be involved in driving the selectivity of the reaction."

"Our plan," says Sigman, "is to take this technique and chase new problems."