Scientists do glass a solid

New theory on how it transitions from a liquid

How does glass transition from a liquid to its familiar solid state? How does this common material transport heat and sound? And what microscopic changes occur when a glass gains rigidity as it cools?

A team of researchers at NYU's Center for Soft Matter Research offers a theoretical explanation for these processes in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Our understanding of glasses as they change state is relatively limited. This is because, unlike other materials such as metals, their constituent particles are in a disorganized, rather than orderly, arrangement. Understanding what in these disordered arrangements decides if the material is liquid or solid remains a long-lasting challenge of physics and chemistry.

The simplest examples of glasses are colloidal suspensions, which behave essentially as hard spheres. Beyond their conceptual interest, they also matter to scientists because they are the basis for an array of consumer products. For instance, colloidal dispersions comprise such everyday items as paint, milk, gelatin, glass, and porcelain. Moreover, understanding how they evolve from liquids to solids is of concern to medical researchers - for example, the clotting of blood.

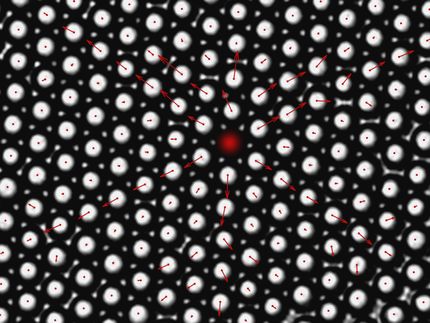

Colloids form a liquid at small density, but become solid when the density is increased beyond some threshold. At that point, crowding effects become important: particles are prisoners of the cage formed by their neighbors. Although they can still wiggle somewhat within their cage, they cannot escape far, forbidding flow. Why the assembly of cages can resist the wiggling of particles in the solid phase is a long-standing debate in the field. Explanations have been proposed in very abstract models, but a simple physical picture of what is going on was lacking.

In their theoretical work, spurred by laboratory observations of colloidal glasses, the researchers propose to use 19th-century concepts developed by Maxwell, the founder of electromagnetism, to study the stability of mechanical structures. Thus concepts widely used in architecture and engineering are now applied at a microscopic level in colloidal glasses. Based on these ideas, the authors developed a theory of the emergence of rigidity.

A curious outcome of their work is the prediction that the wiggling motion of particles in their cage is collective: particles dance in a very coordinated way. The structure of the material is predicted to be such that the dance has the largest amplitude it could possibly have without destroying the solid.

The authors show that this coordinated dance is quantitatively affected by the presence of weak spots in the materials. The description leads to various predictions on the dynamics of the particles, as well as the elastic response of the material and the ability to transport heat in molecular glasses.

Most read news

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.