How ceramics get super-tough

Scientists find new toughening mechanism

Researchers have identified a previously unknown mechanism that makes a rare kind of ceramics super-tough. The findings may show a way to compose super-hard and super-tough ceramics for industrial application, as the team around DESY scientist Dr. Nori Nishiyama reports in the journal Scientific Reports.

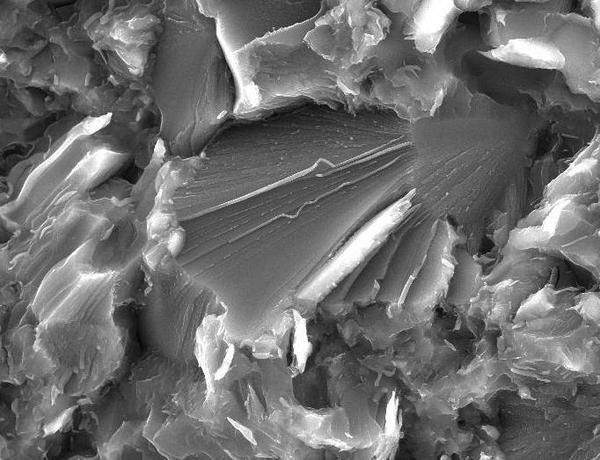

At the fractures wormlike structures made of amorphous silica form (center).

Nori Nishiyama/DESY

The researchers investigated a material called stishovite, a rare version of silica that forms under high pressure for instance in meteorite impacts and inside the earth below about 300 kilometres of depth. Stishovite is a ceramic of the oxide group. “It is the hardest oxide known to date, even harder than ruby or sapphire,” says Nishiyama. While ceramics in general can be very hard, they tend to be very brittle also, breaking easily. Its brittleness prevented stishovite from being used industrially.

But in 2012, Nishiyama and co-workers had synthesized nanocrystals of stishovite and could show that bulk stishovite made up of such nanocrystals is not only very hard, but also becomes very tough, reaching the toughness of zirconia, the toughest ceramic known. The reason for this toughening of stishovite remained elusive until recently.

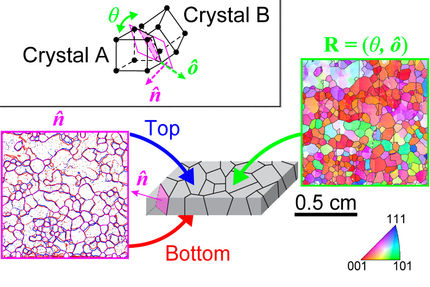

With a clever combination of electron microscopy and X-ray investigations at DESY's synchrotron light source PETRA III (beamline P02.1) and at the Japanese synchrotron light source SPring-8, the researchers could now identify the previously unknown mechanism that makes nanocrystalline stishovite so exceptionally tough. Stishovite forms under high pressure and is only metastable under ambient conditions. Metastable means that if enough energy is added in some form (for instance via a fracture or via high temperature), it switches to a different configuration.

Stishovite uses the energy from a fracture to switch from a tetragonal crystal into amorphous silica, as the researchers found. "Actually, the transformation from stishovite to amorphous silica resembles the melting of ice," explains Nishiyama. "Both are crystal-to-amorphous transformations that occur outside the stability field."

The scientists had produced nanocrystalline bulk stishovite and ripped it apart. They then looked at the fracture sites with an electron microscope. The investigation revealed worm like silica structures that proved to be an amorphous phase of silica. “These 'worms' have diameters of some tens of nanometres,” says Nishiyama. Using X-ray spectroscopy the team could show that about half of the surface in the fracture area is covered by amorphous silica. The more amorphous silica was present, the tougher the fracture area got. This result indicates that the fracture-induced transition to amorphous silica indeed caused the toughening of the stishovite.

“This transition instantaneously doubles the volume of the material, effectively pushing against the fracture and stopping it short,” explains Nishiyama. In a similar way zirconia gets its toughness. On a fracture, it switches from one crystal structure (tetragonal) to another (monoclinic), expanding its volume by 4 per cent. “The transition now observed in stishovite expands the volume by 100 per cent,” underlines Nishiyama. “It may be possible to create ceramics composites for industrial use that can exploit the toughening mechanism of stishovite.”

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!

Topic World Spectroscopy

Investigation with spectroscopy gives us unique insights into the composition and structure of materials. From UV-Vis spectroscopy to infrared and Raman spectroscopy to fluorescence and atomic absorption spectroscopy, spectroscopy offers us a wide range of analytical techniques to precisely characterize substances. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of spectroscopy!