Nanoscale assembly line

ETH researchers have realised a long-held dream: based on an industrial assembly line, they have developed a minuscule production line for the assembly of biological molecules.

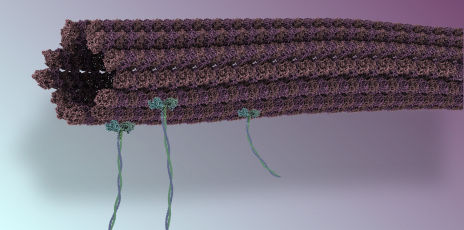

On the nano assembly line, tiny biological tubes called microtubules serve as transporters for the assembly of several molecular objects.

Samuel Hertig

Cars, planes and many electronic products are now built with the help of sophisticated assembly lines. Mobile assembly carriers, on to which the objects are fixed, are an important part of these assembly lines. In the case of a car body, the assembly components are attached in various work stages arranged in a precise spatial and chronological sequence, resulting in a complete vehicle at the end of the line.

The creation of such an assembly line at molecular level has been a long-held dream of many nanoscientists. “It would enable us to assemble new complex substances or materials for specific applications,” says Professor Viola Vogel, head of the Laboratory of Applied Mechanobiology at ETH Zurich. Vogel has been working on this ambitious project together with her team and has recently made an important step. In a paper published in the latest issue of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Lab on a Chip journal, the ETH researchers presented a molecular assembly line featuring all the elements of a conventional production line: a mobile assembly carrier, an assembly object, assembly components attached at various assembly stations and a motor (including fuel) for the assembly carrier to transport the object from one assembly station to the next.

Production line three times thinner than a hair

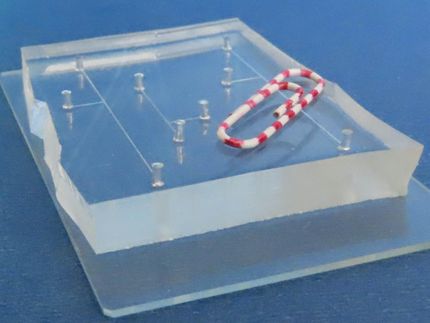

At nano level, the assembly line takes the form of a microfluid platform into which an aqueous solution is pumped. This platform is essentially a canal system with the main canal just 30 micrometres wide – three times thinner than a human hair. Several inflows and outflows lead to and from the canal at right angles. The platform was developed by Vogel’s PhD student Dirk Steuerwald and the prototype was created in the clean room at the IBM Research Centre in Rüschlikon.

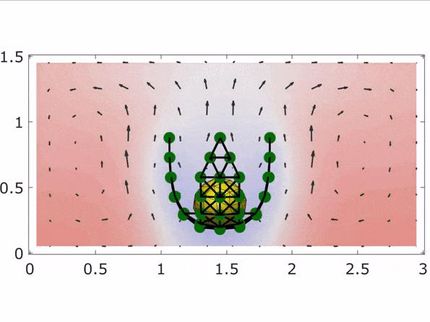

The canal system is fitted with a carpet made of the motor protein kinesin. This protein has two mobile heads that are moved by the energy-rich molecule ATP, which supplies the cells of humans and other life forms with energy and therefore make it the fuel of choice in this artificial system.

Assembling molecules step-by-step

The ETH researchers used microtubules as assembly carriers. Microtubules are string-like protein polymers that together with kinesin transport cargo around the cells. With its mobile heads, kinesin binds to the microtubules and propels them forward. This propulsion is supported by the current generated by the fluid being pumped into the canal system. Five inflows and outflows direct the current in the main canal and divide it into strictly separated segments: a loading area, from where the assembly carriers depart, two assembly stations and two end stations, where the cargo is delivered.

The researchers can add the objects to the system through the lines that supply the assembly segments. In their most recent work, they tested the system using NeutrAvidin, the first molecule that binds to the nanoshuttle. A second component – a single, short strand of genetic material (DNA) – then binds to the NeutrAvidin, creating a small molecular complex.

Technical application still a long way off

Although Vogel’s team has achieved a long-held dream with this work, the ETH professor remains cautious: “The system is still in its infancy. We’re a long way off a technical application.” Vogel believes they have shown merely that the principle works.

She points out that although the construction of such a molecular nanoshuttle system may look easy, a great deal of mental effort and knowledge from different disciplines goes into every single component of the system. The creation of a functional unit from individual components remains a big challenge. “We have put a lot of thought into how to design the mechanical properties of bonds to bind the cargo to the shuttles and then unload it again in the right place.”

The use of biological motors for technical applications is not easy. Molecular engines such as kinesin have to be removed from their biological context and integrated into an artificial entity without any loss of their functionality. The researchers also had to consider how to supply the motors with power, how to build the assembly carriers and what the ‘tracks’ and assembly stations would look like. “These are all separate problems that we have now managed to combine into a functioning whole,” says a pleased Vogel.

Sophisticated products from the nano assembly line

The researchers envision numerous applications, including the selective modification of organic molecules such as protein and DNA, the assembly of nanotechnological components or small organic polymers, or the chemical alteration of carbon nanotubes. “We need to continue to optimise the system and learn more about how we can design the individual components of this nanoshuttle system to make these applications possible in the future,” says the ETH professor. The conditions for further research in this field are excellent: her group is now part of the new NCCR in Basel – Molecular Systems Engineering: Engineering functional molecular modules to factories.