Laser Pulse turns Glass into a Metal

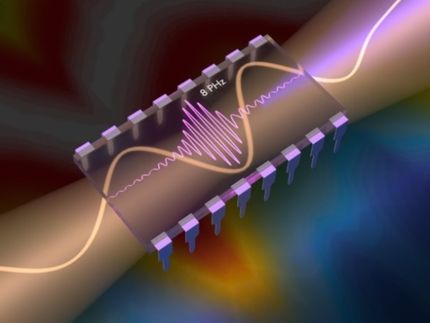

For tiny fractions of a second, quartz glass can take on metallic properties, when it is illuminated be a laser pulse. This has been shown by calculations at the Vienna University of Technology. The effect could be used to build logical switches which are much faster than today’s microelectronics.

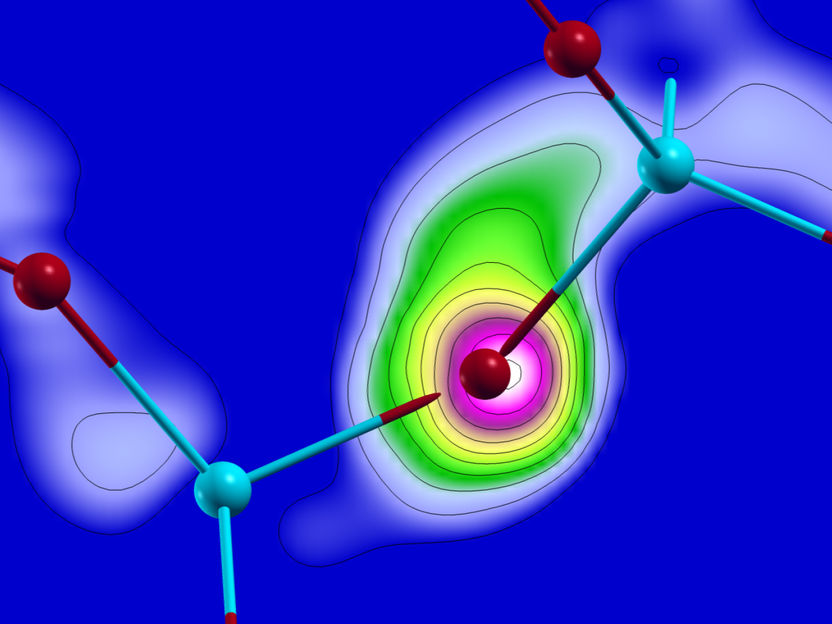

Computer simulations show the electron flux from one atom to the others.

Copyright: TU Wien

Quartz glass does not conduct electric current, it is a typical example of an insulator. With ultra-short laser pulses, however, the electronic properties of glass can be fundamentally changed within femtoseconds (1 fs = 10^-15 seconds). If the laser pulse is strong enough, the electrons in the material can move freely. For a brief moment, the quartz glass behaves like metal. It becomes opaque and conducts electricity. This change of material properties happens so quickly that it can be used for ultra-fast light based electronics. Scientists at the Vienna University of Technology (TU Wien) have now managed to explain this effect using large-scale computer simulations.

Watching Small Things on Ultra-Fast Time Scales

In recent years, ultra-short laser pulses of only a few femtoseconds have been used to investigate quantum effects in atoms or molecules. Now they can also be used to change material properties. In an experiment (at the Max-Planck Institute in Garching, Germany) electric current has been measured in quartz glass, while it was illuminated by a laser pulse. After the pulse, the material almost immediately returns to its previous state. Georg Wachter, Christoph Lemell and Professor Joachim Burgdörfer (TU Wien) have now managed to explain this peculiar effect, in collaboration with researchers from the Tsukuba University in Japan.

Quantum mechanically, an electron can occupy different states in a solid material. It can be tightly bound to one particular atom or it can occupy a state of higher energy in which it can move between atoms. This is similar to the behaviour of a little ball on a dented surface: when it has little energy, it remains in one of the dents. If the ball is kicked hard enough, it can move around freely.

“The laser pulse is an extremely strong electric field, which has the power to dramatically change the electronic states in the quartz”, says Georg Wachter. “The pulse can not only transfer energy to the electrons, it completely distorts the whole structure of possible electron states in the material.”

That way, an electron which used to be bound to an oxygen atom in the quartz glass can suddenly change over to another atom and behave almost like a free electron in a metal. Once the laser pulse has separated electrons from the atoms, the electric field of the pulse can drive the electrons in one direction, so that electric current starts to flow. Extremely strong laser pulses can cause a current that persists for a while, even after the pulse has faded out.

Several Quantum Processes at the Same Time

“Modelling such effects is an extremely complex task, because many quantum processes have to be taken into account simultaneously”, says Joachim Burgdörfer. The electronic structure of the material, the laser-electron interaction and also the interactions between the electrons has to be calculated with supercomputers. “In our computer simulations, we can study the time evolution in slow motion and see what is actually happening in the material”, says Burgdörfer.

In the transistors we are using today, a large number of charge carriers moves during each switching operation, until a new equilibrium state is reached, and this takes some time. The situation is quite different when the material properties are changed by the laser pulse. Here, the switching process results from the change of the electronic structure and the ionization of atoms. “These effects are among the fastest known processes in solid state physics”, says Christoph Lemell. Transistors usually work on a time scale of picoseconds (10^-12 seconds), laser pulses could switch electric currents a thousand times faster.

The calculations show that the crystal structure and chemical bonds in the material have a remarkably big influence on the ultra-fast current. Therefore, experiments with different materials will be carried out to see how the effect can be used even more efficiently.