Using antineutrinos to monitor nuclear reactors

Astroparticle physics methodology applied to nuclear facility monitoring

When monitoring nuclear reactors, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has to rely on input given by the operators. In the future, antineutrino detectors may provide an additional option for monitoring. However, heretofore the cumulative antineutrino spectrum of uranium 238 fission products was missing. Physicists at Technische Universität München (TUM) have now closed this gap using fast neutrons from the Heinz Maier Leibnitz Neutron Research Facility (FRM II).

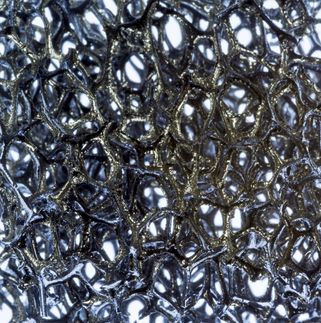

Dr. Nils Haag developed an experimental setup that allowed him to determine the missing spectrum of uranium 238.

Wenzel Schuermann / TU München

In addition toneutrons, the fission reaction of nuclear fuels like plutonium or uranium releases antineutrinos. These are also electrically neutral, but can pass matter very easily, which is why they can be discerned only in huge detectors. Recently, however, detectors on the scale of only one cubic meter have been developed. They can measure antineutrinos from a reactor core, which has generated great interest at theIAEA.

Prototypes of these detectors already exist and collect data at distances of around 10 meters from a reactor core. Changes in the composition of nuclear fuels in the reactor – for example, when weapons-grade U-239 is removed – can be determined by analyzing the energy and rate of antineutrinos. This would free the IAEA from having to rely on representations of reactor operators.

Antineutrino spectrum of uranium 238 revealed

In the 1980s the antineutrino spectra of three main fuel isotopes, uranium 235, plutonium 239 and plutonium 241, were determined. However, the antineutrino spectrum of the fourth main nuclear fuel, uranium 238, which accounts for approximately 10 percent of the total antineutrino flux, remained unclear. It had only been estimated using inaccurate theoretical calculations and thus limited the accuracy of the antineutrino predictions.

Dr. Nils Haag from theChair of Experimental Astroparticle Physicsat TU München recently developed an experimental setup at theFRM IIthat allowed him to determine the missing spectrum of uranium 238. "I needed a high flux of fast neutrons to induce the fission of the U-238," says the physicist. This is why he located his experimental setup at the NECTAR radiography and tomography station of the FRM II – a source of fast neutrons.

Second detector for background-free measurement

The neutrons induce nuclear fission in a film of U-238. The radioactive decay products then emit electrons and antineutrinos. The electrons were investigated using a scintillator – a block of plastics that converts the kinetic energy of the electrons into light. A photomultiplier then translates this into electrical signals.

The nuclear decay also generates gamma radiation that produces unwanted events in the scintillator. Therefore, Haag placed a second detector right in front of the scintillator: a so-called multi-wire proportional chamber. Since only charged particles like electrons trigger a signal in the gas detector, the researcher was able to determine and subtract the proportion of gamma radiation. Haag then inferred the antineutrino spectrum using this background-free measurement data.

Method allows better monitoring of reactor cores

The measurement of the antineutrino spectrum can be used to monitor the status, performance and even composition of reactor cores. "Our results open the door to predict with significantly higher accuracy the expected antineutrino spectrum emitted by a reactor running on a fuel composition reported by the operator," explains Dr. Nils Haag. "Deviations of antineutrino detector measurement data from expected reactor signals can thus be exposed."

The development of this methodology is embedded in basic research on the phenomenon of so-called "sterile" antineutrinos. Comparing previously made measurements and predictions of reactor antineutrino spectra gave rise to the assumption that some of the antineutrinos turned "sterile" after being produced. They were then no longer able to react with other matter. A better understanding of this effect would expand our knowledge of elementary physical processes.

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the DFG Excellence Cluster"Origin and Structure of the Universe"at TUM.