TU Vienna develops light transistor

TU Vienna has managed to turn the oscillation direction of beams of light -- simply by applying an electrical current to a special material. This way, a transistor can be built that functions with light instead of electrical current.

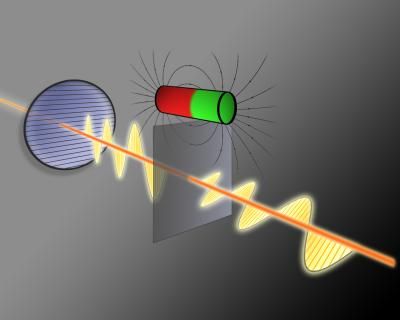

The oscillation direction of a light wave is changed as it passes through a thin layer of a special material.

Vienna University of Technology

Light can oscillate in different directions, as we can see in the 3D cinema: Each lens of the glasses only allows light of a particular oscillation direction to pass through. However, changing the polarization direction of light without a large part of it being lost is difficult. The TU Vienna has now managed this feat, using a type of light – terahertz radiation – that is of particular technological importance. An electrical field applied to an ultra-thin layer of material can turn the polarisation of the beam as required. This produces an efficient transistor for light that can be miniaturised and used to build optical computers.

Rotated light – the Faraday effect

Certain materials can rotate the polarization direction of light if a magnetic field is applied to them. This is known as the Faraday effect. Normally, this effect is minutely small, however. Two years ago, Prof. Andrei Pimenov and his team at the Institute of Solid State Physics of TU Vienna, together with a research group from the University of Würzburg, managed to achieve a massive Faraday effect as they passed light through special mercury telluride platelets and applied a magnetic field.

At that time, the effect could only be controlled by an external magnetic coil, which has severe technological disadvantages. "If electro-magnets are used to control the effect, very large currents are required", explains Andrei Pimenov. Now, the turning of terahertz radiation simply by the application of an electrical potential of less than one volt has been achieved. This makes the system much simpler and faster.

It is still a magnetic field that is responsible for the fact that the polarisation is rotated, however, it is no longer the strength of the magnetic field that determines the strength of the effect, but the amount of electrons involved in the process, and this amount can be regulated simply by electrical potential. Hence only a permanent magnet and a voltage source suffice, which is technically comparatively easy to manage.

Terahertz radiation

The light used for the experiments is not visible: it is terahertz radiation with a wavelength of the order of one millimetre. "The frequency of this radiation equates to the clock frequency that the next but one generation of computers may perhaps achieve", explains Pimenov. "The components of today's computers, in which information is passed only in the form of electrical currents, cannot be fundamentally improved. To replace these currents with light would open up a range of new opportunities." It is not only in hypothetical new computers that it's important to be able to control beams of radiation precisely with the newly developed light turning mechanism: terahertz radiation is used today for many purposes, for example for imaging methods in airport security technology.

Optical transistors

If light is passed through a polarisation filter, dependent on the polarisation direction, it is either allowed to pass through or is blocked. The rotation of the beam of light (and thus the electrical potential applied) therefore determines whether a light signal is sent or blocked. "This is the very principle of a transistor", explains Pimenov: "The application of an external voltage determines whether current flows or not, and in our case, the voltage determines whether the light arrives or not." The new invention is therefore the optical equivalent of an electrical transistor.

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.