Chemical chameleon tamed

Computer simulations show: protonated methane is tamed by microsolvation

Advertisement

How you get the chameleon of the molecules to settle on a particular “look” has been discovered by RUB chemists led by Professor Dominik Marx. The molecule CH5+ is normally not to be described by a single rigid structure, but is dynamically flexible. By means of computer simulations, the team from the Centre for Theoretical Chemistry showed that CH5+ takes on a particular structure once you attach hydrogen molecules. “In this way, we have taken an important step towards understanding experimental vibrational spectra in the future”, says Dominik Marx.

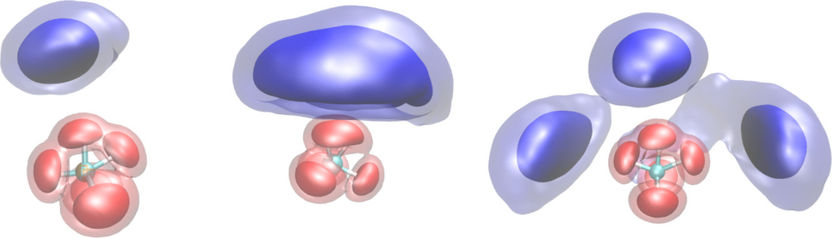

Giving the “chameleon molecule" structure: Depending on how many H2 solvent molecules (blue) attach to the CH5+ molecule, the area in which the hydrogen atoms of the CH5+ molecule move changes (red). Its structure is thus partially “frozen”. The areas represent quantum mechanical probability densities at a temperature of 20 Kelvin.

© A. Witt, S. Ivanov, D. Marx

In the CH5+ molecule, the hydrogen atoms are permanently on the move

The superacid CH5+, also called protonated methane, occurs in outer space - where new stars are formed. Researchers already discovered the molecule in the 1950s, but many of its features are still unknown. Unlike conventional molecules in which all the atoms have a fixed position, the five hydrogen atoms in CH5+ are constantly moving around the carbon centre. Scientists speak of “hydrogen scrambling”. This dynamically flexible structure has been explained by the research groups led by Dominik Marx and Stefan Schlemmer of the University of Cologne as part of a long-term collaboration. Marx‘s team now wanted to know if the structure can be “frozen” under certain conditions by attaching solvent molecules – a process called microsolvation.

Microsolvatation: addition of hydrogen molecules to CH5+ one by one

To this end, the chemists surrounded the CH5+ molecule in the virtual lab with a few hydrogen molecules (H2). Here, the result is the same as when dissolving normal ions in water: a relatively tightly bound shell of water molecules attaches to each ion in order to then transfer individual ions with several solvent molecules bound to them to the gas phase. To describe the CH5+ hydrogen complexes, classical ab initio molecular dynamics simulations are not sufficient. The reason is that “hydrogen scrambling” is based on quantum effects. Therefore Marx’s group used a fully quantum mechanical method which they developed in house, known as ab initio path integral simulation. With this, the essential quantum effects can be taken into account dependent on the temperature.

Hydrogen molecules give the CH5+ molecule “structure”

The chemists carried out the simulations at a temperature of 20 Kelvin, which corresponds to -253 degrees Celsius. In the non-microsolvated form, the five hydrogen atoms in the CH5+ molecule are permanently changing positions even at such low temperatures – and entirely due to quantum mechanical effects. If CH5+ is surrounded by hydrogen molecules, this “hydrogen scrambling” is, however, significantly effected and may even completely come to a halt: the molecule assumes a rudimentary structure. How this looks exactly depends on how many hydrogen molecules are attached to the CH5+ molecule. “What especially interests me is if superfluid helium – like the hydrogen molecules here – can also stop hydrogen scrambling in CH5+” says Marx. Experimental researchers use superfluid helium to measure high-resolution spectra of molecules embedded in such droplets. For CH5+ this has so far not been possible. In the superfluid phase, the helium atoms are, however, indistinguishable due to quantum statistical effects. To be able to describe this fact, the theoretical chemists at the RUB spent many years developing a new, even more complex path-integral-based simulation method that has recently also been applied to real problems.