Researchers double down on heat to break up cellulose, produce fuels and power

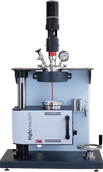

Nicholas Creager recently pointed to the nuts and bolts of one of Iowa State University's latest biofuel machines.

Photo: Bob Elbert/Iowa State University

The 6-inch diameter, stainless steel pipe is the pressure vessel, which is essential for the system's operation, said Creager, a doctoral student in mechanical engineering and biorenewable resources and technology. It's a little over three feet long and about a foot across. It can contain pressures up to 700 pounds per square inch.

Then Creager picked up a dark gray pipe that's a few inches across, is wrapped in insulation and fits inside the pressure vessel. It's the system's reactor. It's made of silicon carbide and can operate at temperatures exceeding 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

Next was a finger-sized nozzle that mixes bio-oil with oxygen and sprays it into the top of the reactor.

Add a bunch of toggle switches, electronics, pipes, a sturdy frame and some very thick bolts and you have a bio-oil gasifier. It will allow Iowa State researchers to combine two thermochemical technologies to produce the next generation of fuels from renewable resources such as corn stalks and wood chips.

First, biomass is fed into a fast pyrolysis machine where it's quickly heated without oxygen. The end product is a thick, brown oil that can be divided and further processed into fuels. Researchers sometimes describe bio-oil as densified biomass that's much easier to handle and transport than raw biomass.

Second, the bio-oil is sprayed into the top of the gasifier where heat and pressure vaporize it to produce a combination of (mostly) hydrogen and carbon monoxide that's called synthesis gas.

That gas can be processed into transportation fuels. It can also be used as boiler fuel to create the steam that turns turbines to produce electricity.

"We hope to be able to use cellulosic biomass as opposed to using corn grain for the production of fuels," said Robert C. Brown, the director of Iowa State's Bioeconomy Institute, an Anson Marston Distinguished Professor in Engineering and the Gary and Donna Hoover Chair in Mechanical Engineering. "This helps us move toward cellulosic biofuels."

Brown said researchers have yet to perfect ways to biologically break down plant cellulose to get at the sugars that are converted to fuels. And so the Iowa State researchers are turning to nature's solution.

"Nature uses high temperatures to quickly decompose biomass," Brown said.

The bio-oil gasifier has been fully operational since June and has been converting bio-oil made from pine wood into synthesis gas. As the project moves beyond its startup phase, researchers will use bio-oil produced by Iowa State researchers and fast pyrolysis equipment.

The gasifier was built as part of a two-year, nearly $1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy. Another three-year, $450,000 grant from the Iowa Energy Center will allow researchers to study and refine bio-oil gasification.

Song-Charng Kong, an associate professor of mechanical engineering who's leading the latter project, will build a computer simulation model of bio-oil gasification. The model will take into account changes in temperature, pressure and biomass. It will allow researchers to understand, predict and ultimately improve the gasification process.

The project will also develop a systems simulation tool that allows researchers to examine the technical, economic and big picture implications of bio-oil gasification. And finally, the project will develop a virtual reality model of a full-size plant that will allow researchers to see, study and improve a plant before construction crews are ever hired.

"The physics and chemistry will be behind all these models and images," Kong said. "This is a very new area to study. We can use these models as a tool to understand what will happen as this technology is scaled up."

Once the machine is fully tested and operating at full speed, Creager said it could continuously gasify nearly 4.5 pounds of bio-oil an hour.

That's enough to help researchers understand how the technology could one day contribute to an advanced bioeconomy.