Nano-velcro clasps heavy metal molecules in its grips

Researchers develop nano-strips for inexpensive testing of mercury levels in our lakes and oceans with unprecedented sensitivity

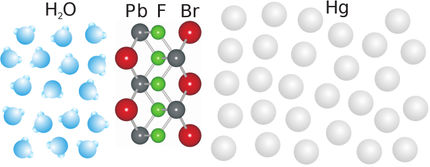

mercury, when dumped in lakes and rivers, accumulates in fish, and often ends up on our plates. A Swiss-American team of researchers led by Francesco Stellacci at the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) and Bartosz Grzybowski at Northwestern University has devised a simple, inexpensive system based on nanoparticles, a kind of nano-velcro, to detect and trap this toxic pollutant as well as others. The particles are covered with tiny hairs that can grab onto toxic heavy metals such as mercury and cadmium. This technology makes it possible to easily and inexpensively test for these substances in water and, more importantly, in the fish that we eat. Their new method can measure methyl mercury, the most common form of mercury pollution, at unprecedentedly small attomolar concentrations. The system is outlined in the journal Nature Materials.

Methyl mercury, toxic and difficult to monitor

Researchers are particularly interested in detecting mercury. Its most common form, methyl mercury, accumulates as one goes up the food chain, reaching its highest levels in large predatory fish such as tuna and swordfish. In the US, France and Canada, public health authorities advise pregnant women to limit fish consumption because mercury can compromise nervous system development in the developing fetus.

"The problem is that current monitoring techniques are too expensive and complex," explains Constellium Chair holder at EPFL and co-author Francesco Stellacci. "We periodically test levels of mercury in drinking water, and if those results are good, we make the assumption that levels are acceptable in between those testing periods." But industrial discharge fluctuates.

A simple, inexpensive new technology

The technology developed by the Swiss-American team is simple to use. A strip of glass covered with a film of "hairy" nanoparticles is dipped into the water. When an ion – a positively charged particle, such as a methyl mercury or cadmium ion – gets in between two hairs, the hairs close up, trapping the pollutant.

A voltage-measuring device reveals the result; the more ions there are trapped in the nano-velcro, the more electricity it will conduct. So to calculate the number of trapped particles, all one needs to do is measure the voltage across the nanostructure.

By varying the length of the nano-hairs, the scientists can target a particular kind of pollutant. "The procedure is empirical," explains Stellacci. Methyl mercury, fortunately, has properties that make it extremely easy to trap without accidentally trapping other substances at the same time; thus the results are very reliable.

The interesting aspect of this approach is that the 'reading' glass strip could costs less than 10 dollars, while the measurement device will cost only a few hundreds of dollars. The analysis can be done in the field, so the results are immediately available. "With a conventional method, you have to send samples to the laboratory, and the analysis equipment costs several million dollars," notes Stellacci.

Convincing tests in Lake Michigan and Florida

The researchers tested the system in Lake Michigan, near Chicago. Despite the high level of industry in the region, mercury levels were extremely low. "The goal was to compare our measurements to FDA measurements done using conventional methods," explains Stellacci. "Our results fell within an acceptable range."

A mosquito fish from the Everglades in Florida was also tested. This species is not very high on the food chain and thus does not accumulate high levels of mercury in its tissues. "We measured tissue that had been dissolved in acid. The goal was to see if we could detect even minuscule quantities." says Bartosz Grzybowski, Burgess Professor of Chemistry and Director of Non-Equilibrium Energy Research Center at Northwestern University. The United States Geological Survey reported near-identical results after analyzing the same sample.

From quantum to real applications

"I think it is quite incredible," Grzybowski adds, "how the complex principles of quantum tunneling underlying our device translate into such an accurate and practically useful device. It is also notable that our system - through some relatively simple chemical modifications - can be readily adapted to detect other toxic species" Researchers have already demonstrated the detection of cadmium with a very high femtomolar sensitivity.

"With this technology, it will be possible to conduct tests on a much larger scale in the field, or even in fish before they are put on the market," says lead author Eun Seon Cho. This is a necessary public health measure, given the toxic nature of methyl mercury and the extremely complex manner in which it spreads in the environment and accumulates in living tissues.

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

NANOPHOX CS by Sympatec

Particle size analysis in the nano range: Analyzing high concentrations with ease

Reliable results without time-consuming sample preparation

Eclipse by Wyatt Technology

FFF-MALS system for separation and characterization of macromolecules and nanoparticles

The latest and most innovative FFF system designed for highest usability, robustness and data quality

DynaPro Plate Reader III by Wyatt Technology

Screening of biopharmaceuticals and proteins with high-throughput dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Efficiently characterize your sample quality and stability from lead discovery to quality control

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Lafarge Perlmooser GmbH - Mannersdorf am Leithagebirge, Austria

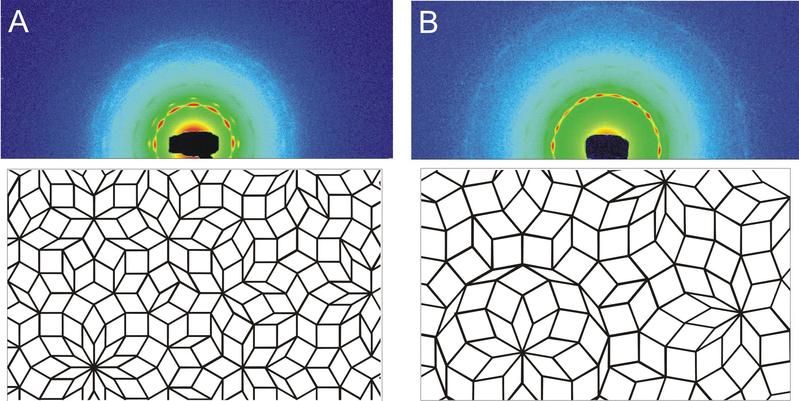

Colloidal Quasi-Crystals Discovered

LION bioscience announces partnership with ACE BioSciences

NanoSight is recognised as an ISO9001 Certified Company

Clariant continues to increase sales - Clariant improves profitability and remains on track to meet 2017 outlook

Brenntag completes acquisition of ISM/Salkat Group in Australia and New Zealand

EnviroDTS GmbH - Friedberg, Germany

True Surface Microscopy wins Microscopy Today Innovation Award 2011 - Third Consecutive Award

International_Mineralogical_Association

DKSH and Clariant build strategic partnership covering India, the Philippines and Vietnam - Regional distribution partnership for the Industrial & Consumer Specialty Business Unit