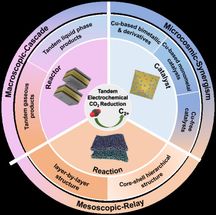

New materials could slash energy costs for CO2 capture

Study IDs 'zeolite' minerals that are one-third more efficient for carbon capture

A detailed analysis of more than 4 million absorbent minerals has determined that new materials could help electricity producers slash as much as 30 percent of the "parasitic energy" costs associated with removing carbon dioxide from power plant emissions.

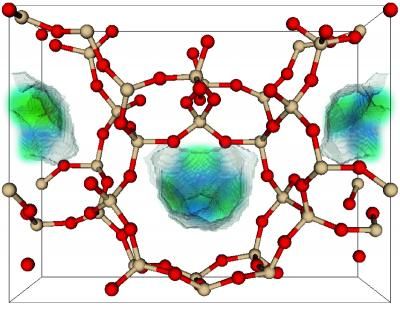

In this zeolite structure, the arrangement of oxygen atoms (red) and silicon atoms (tan) influences the regions in the pores (colored surface) where CO2 can be captured.

B. Smit/UC-Berkeley

The research by scientists at Rice University, the University of California, Berkeley, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) and the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) was published in the journal Nature Materials.

Coal- and natural-gas-fired power plants account for about half of the carbon dioxide (CO2) that humans add to the atmosphere each year, but current technology for capturing that CO2 and storing it underground can gobble up as much as one-third of the steam the plant could otherwise use to make electricity.

In the new study, researchers found that commonly used industrial minerals called zeolites could significantly improve the energy efficiency of "carbon capture" technology.

"It looks like we can beat the current state-of-the-art technology by about 30 percent, and not just with one or two zeolites," said study co-author Michael Deem, Rice's John W. Cox Professor of Bioengineering and professor of physics and astronomy. "Our analysis showed that dozens of zeolites are more efficient than the amine absorbents currently used for CO2 capture."

Commercial power plants do not capture CO2 on a large scale, but the technology has been tested at pilot plants. At test plants, flue gases are funneled through a bath of ammonia-like chemicals called amines. The amines are then boiled to release the captured CO2, and additional energy is required to compress the CO2 so it can be pumped underground. The "parasitic energy" costs associated with current technology is high; up to one-third of the steam that could be used to generate electricity is siphoned off to boil the amines and liquefy the CO2.

Deem said the new study is the first to compare the "parasitic energy" costs for a whole class of carbon-capture materials. The study found dozens of zeolites that could remove CO2 from flue gas for a lower energy cost than amines could.

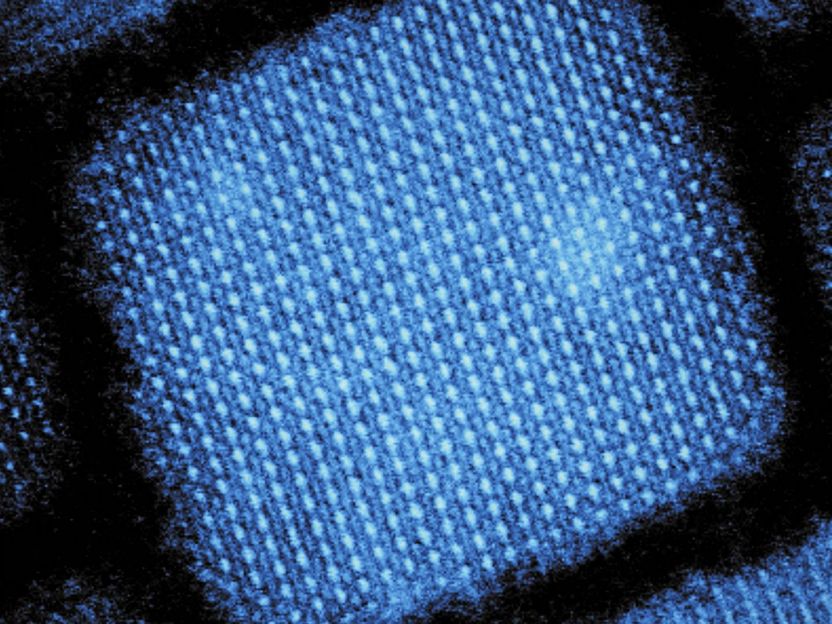

Zeolites are common minerals made mostly of silicon and oxygen. About 40 exist in nature, and there are about 160 man-made types. All zeolites are highly porous -- like microscopic Swiss cheese -- and the pore sizes and shapes vary depending upon how the silicon and oxygen atoms are arranged. The pores act like tiny reaction vessels that capture, sort and spur chemical reactions of various kinds, depending upon the size and shape of the pores. The chemical industry uses zeolites to refine gasoline and to make laundry detergent and many other products.

In 2007, Deem and colleagues used computers to calculate millions of atomic formulations for zeolites, and they have continued to add information to the resulting catalog, which contains about 4 million zeolite structures.

In the new study, the zeolite database was examined with a new computer model designed to identify candidates for CO2 capture. The new model was created by a team led by co-author Berend Smit, UC Berkeley's Chancellor's Professor in the departments of chemical and biomolecular engineering and of chemistry and a faculty senior scientist at LBNL. Smit and his UC Berkeley group worked with study co-author Abhoyjit Bhown, a technical executive at EPRI, to establish the best criteria for a good carbon capture material. Focusing on the energy costs of capture, release and compression, they created a formula to calculate the energy consumption for any materials in the zeolite database.

Running the painstaking calculations to compare the CO2-capture abilities of each zeolite would have taken approximately five years with standard central processing units (CPUs), so Smit and his colleagues at UC-Berkeley and LBNL created a new way to run the calculations on graphics processing units, or GPUs -- the processors used in PC graphics cards. Deem said the GPU technique cut the compute time to about one month, which made the project feasible.

Smit said, "Our database of carbon capture materials is going to be coupled to a model of a full plant design, so if we have a new material, we can immediately see whether this material makes sense for an actual design."

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Demand For Advanced Technologies Anchors Modest Growth In Centrifugal And Turbine Pumps Market

A dream of foam

New material could expand applications and lower costs for solid oxide fuel cells

Coffee physics

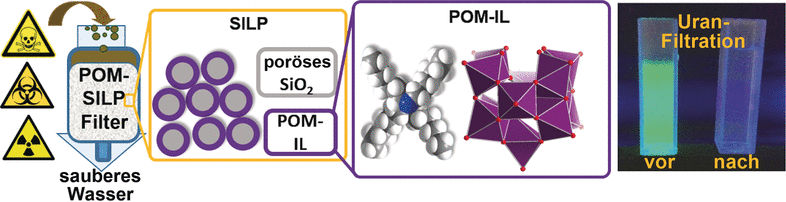

Composite material for water purification - Removal of multiple contaminants from water by supported ionic liquid phases

Extremely bright and fast light emission

Donald_Mackay_(scientist)