Tracking down volatile mercury in the Atlantic

Marine chemists from Warnemünde identify unexpected places and seasons of higher emission

Advertisement

For the first time, mercury emissions of the Atlantic Ocean were investigated by comprehensive measurements, performed under the leadership of researchers from the Leibniz Institute of Baltic Sea Research in Warnemünde. The scientists Joachim Kuss, Christoph Zülicke, Christa Pohl and Bernd Schneider sought to answer two questions: 1. What role do the seasons play in the processes that cause mercury to be released by the oceans as a volatile gas? 2. What is the spatial distribution of mercury in the Atlantic Ocean?

Mercury is potentially harmful to both humans and animals. To understand its behavior in the environment is therefore of great societal interest. However, although the amount of mercury circulating in the environment has been tripled by human activities, broad-ranging and long-term research programs have yet to completely elucidate the steps comprising the mercury cycle.

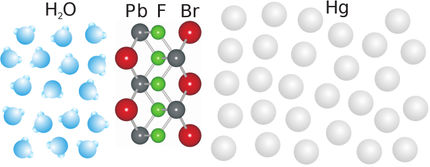

Mercury is mainly emitted into the atmosphere and subsequently distributed worldwide as volatile elemental mercury. Within the atmosphere, mercury is slowly oxidized and then becomes bound to dust particles. Rainfall washes the dust together with the bound mercury out of the atmosphere, with subsequent transport of the heavy metal into the oceans. While many other such metals partially exit the cycle, sinking to the sea floor attached to particles, mercury can be converted back to the volatile elemental form by exposure to light, either with or without the involvement of algae. By this route, it escapes the oceans and is distributed further. The amount of mercury that is actually emitted is difficult to determine and to date only few measurement data have been available.

During two research cruises with the r/v Polarstern, traveling between the English Channel and South Africa and – half a year later – from southern South America to Germany, an intensive measuring campaign was undertaken to determine the concentration of volatile mercury both in the surface waters and in the atmosphere.

For the IOW researchers, it was astonishing to recognize that, in contrast to their expectations, most of the elemental mercury was not found in the industrialized temperate zone of the Northern hemisphere but in the tropical zone of the Atlantic Ocean. According to Joachim Kuss and his colleagues, this fact can be explained by the underlying conditions, which strongly favor the production of volatile mercury. The tropical climate promotes the emission of mercury in a process made up of several successive steps.

Strong tropical rainfalls cause oxidized mercury to be washed out of the atmosphere into the ocean in a very effective manner. Afterwards, intense solar radiation converts the mercury into its volatile form, which in turn concentrates within the upper 20 m of the tropical Atlantic. However, mercury emission is not initiated until the winds become stronger. This task is fulfilled by the powerful trade winds once they pass over those regions of the sea in which the surface waters are enriched in mercury. Thus, year-round, the tropical Atlantic provides the optimum prerequisites allowing the escape of mercury.

The observations resulted in another new hypothesis: until now, researchers working on atmospheric models assumed that the seasonal emission of mercury from the oceans is caused by solar radiation and the activity of algae.

According to the new measurements, however, the presumed overall coupling to algal growth seems to be incorrect, as it would require very strong emissions coinciding with the peak of the bloom. But during the springtime bloom (April/May in the North Atlantic; November in the South Atlantic) no increase in mercury emissions was detected. Instead, high-level emissions were found to occur in autumn (November in the North Atlantic; April/May in the South Atlantic).

The comprehensive measurements performed by the IOW scientists were used to estimate annual global mercury emissions. According to these projections, two million kilograms of mercury are emitted annually by the global oceans. This nearly equals the total annual anthropogenic emissions and is in good accordance with theoretical predictions derived from atmospheric models. However, deviations are clearly evident with respect to the seasonal and spatial contributions of the processes. While the results of the Warnemünde researchers provide new insight in this context, further global measuring campaigns and local-process studies are required for a deeper understanding of the marine mercury cycle.