Structure of plastic solar cells impedes their efficiency

Advertisement

A team of researchers from North Carolina State University and the U.K. has found that the low rate of energy conversion in all-polymer solar-cell technology is caused by the structure of the solar cells themselves. They hope that their findings will lead to the creation of more efficient solar cells.

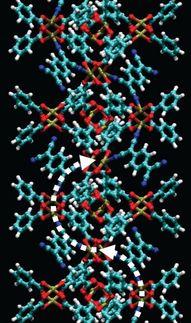

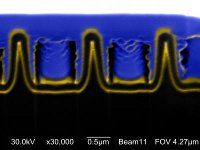

Polymeric solar cells are made of thin layers of interpenetrating structures from two different conducting plastics and are increasingly popular because they are both potentially cheaper to make than those currently in use and can be "painted" or printed onto a variety of surfaces, including flexible films made from the same material as most soda bottles. However, these solar cells aren't yet cost-effective to make because they only have a power conversion rate of about three percent, as opposed to the 15 to 20 percent rate in existing solar technology.

"Solar cells have to be simultaneously thick enough to absorb photons from the sun, but have structures small enough for that captured energy – known as an exciton – to be able to travel to the site of charge separation and conversion into the electricity that we use," says Dr. Harald Ade, professor of physics and one of the authors of a paper describing the research. "The solar cells capture the photons, but the exciton has too far to travel, the interface between the two different plastics used is too rough for efficient charge separation, and its energy gets lost."

The researchers' results appear online in Advanced Functional Materials and Nano Letters.

In order for the solar cell to be most efficient, Ade says, the layer that absorbs the photons should be around 150-200 nanometers thick. (A nanometer is thousands of times smaller than the width of a human hair.) The resulting exciton, however, should only have to travel a distance of 10 nanometers before charge separation. The way that polymeric solar cells are currently structured impedes this process.

Ade continues, "In the all-polymer system investigated, the minimum distance that the exciton must travel is 80 nanometers, the size of the structures formed inside the thin film. Additionally, the way devices are currently manufactured, the interface between the structures isn't sharply defined, which means that the excitons, or charges, get trapped. New fabrication methods that provide smaller structures and sharper interfaces need to be found."

Ade and his team plan to look at different types of polymer-based solar cells to see if their low efficiencies are due to this same structural problem. They hope that their data will lead chemists and manufacturers to explore different ways of putting these cells together to increase efficiency.

"Now that we know why the existing technology doesn't work as well as it could, our next steps will be in looking at physical and chemical processes that will correct for those problems. Once we get a baseline of efficiency, we can redirect research and manufacturing efforts."