Stretched polymer snaps back smaller than it started

Advertisement

Crazy bands are cool because no matter how long they've been stretched around a kid's wrist, they always return to their original shape, be it a lion or a kangaroo. Now a Duke and Stanford chemistry team has found a polymer molecule that's so springy it snaps back from stretching much smaller than it was before. Duke graduate student Jeremy Lenhardt and associate professor Stephen Craig have been systematically hunting through a library of polymers in search of a molecule that might be useful for "self-healing" materials. They hope to find a polymer that can trigger a chemical reaction when it is stretched and enable a material to build its own repairs.

Imagine a sheet of Saran Wrap that could fix a microscopic puncture before the hole ever got big enough to see. This would require that the polymer molecules immediately around the tear could somehow jump into action and perform new chemistry to build bridges across the hole.

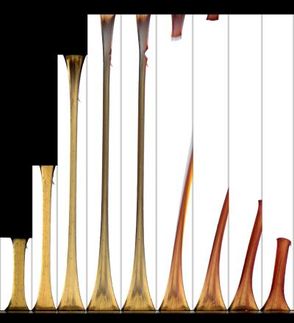

To stretch polymers and see what happens to them, Lenhardt uses an apparatus that pumps up and down on a solution filled with polymers, pressurizing it and depressurizing it 20,000 times a second which causes tiny bubbles to form fleetingly. The void created by the bubbles exerts a tug on the ends of some of the polymers in the solution and stretches them, if only for a billionth of a second.

"Think of two rafts going down a river with a rope between them," Craig explained. "As the first raft enters a rapids and accelerates forward, that rope – the polymer – gets pulled taught and stretches."

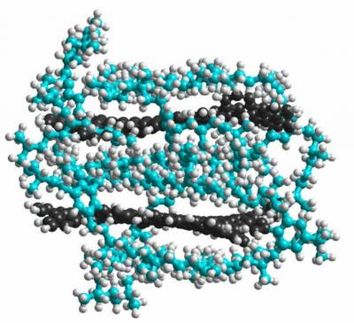

Over and over Lenhardt ran the experiment, characterizing different polymer species that became more reactive when stretched, potentially able to do "stress-induced chemistry." Then, while looking at polymers that contained tiny ring-shaped molecules called gem-difluorocyclopropanes (gDFC), he was surprised to find that some of these molecules emerged from the stretching noticeably shorter than when they went in. A technique called nuclear magnetic resonance had revealed the shapes of the rings after pulling and shown that they were, in fact, shorter. But not only were the gDFCs snapping back smaller than they started, it also appeared that before snapping back they were actually trapped in an unusual stretched state far longer than normal, a reactive state called a 1,3-diradical.

Normally, as a molecule goes through a reaction, it passes through a special point known as a transition state, and stays there for only ten to a hundred femtoseconds, "a tenth of a millionth of a millionth of a second," Craig said. This makes it extraordinary hard to actually watch chemistry happen, so chemists usually can only infer what happens at the transition state by what they've seen before and after.

Work by their Stanford collaborators showed that the trapped 1,3-diradicals are in fact one type of these usually fast-moving transition states, but in Lenhardt's experiments they were essentially stopped in their tracks and trapped for nanoseconds, tens of thousands of times longer than usual.

This might be a window for watching transition states in action, Craig said. "We can trap these things long enough to probe new facets of their reactivity."