Attosecond real-time Observation of a Quantum Hole

For the first time ever, physicists from the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics (LAP) at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum optics have observed what occurs inside an atom from which a single electron has been ejected.

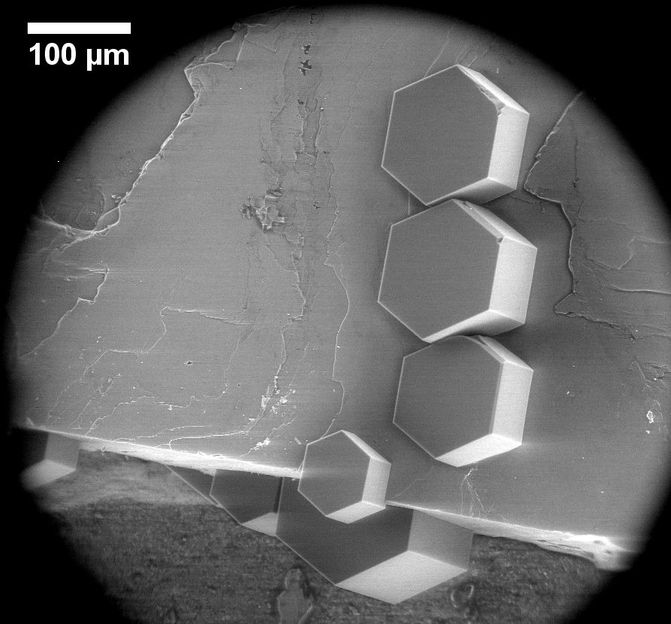

A sequence of snapshots showing the oscillatory motion of a valence electron inside an atomic ion, as reconstructed from attosecond measurements.

Dr. Christian Hackenberger, Ludwig-Maximillians University, Munich, Germany

An international team from the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics, led by Prof. Ferenc Krausz at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, in collaborations with researchers from the United States and Saudi Arabia, have observed, for the first time, the quantum-mechanical behaviour occurring at the location in a noble gas atom where, shortly before, an electron had been ejected from its orbit. The researchers achieved this result using light pulses which last only slightly longer than 100 attoseconds.

Quantum particles, such as electrons, are volatile entities, governed by the laws of quantum mechanics. Movements of electrons in their atomic orbitals last for just a few attoseconds. One attosecond is one billionth of one billionth of a second. What exactly the elementary particles do in the atoms’ atmosphere is, currently, largely unknown. It is, however, clearly understood that one cannot determine both the momentum and location of a particle at the same time. Consequently, the quantum mechanical motion of these elementary particles can be described in terms of a cloud called the “probability density of the particles” subject to rapid pulsation following an excitation.

Now, for the first time, the international team from the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics (LAP) have succeeded in observing how an electron cloud moves with time when one of the electrons in an atom is ejected by a pulse of light. The research collaboration included physicists from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics at Garching, the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich, the King Saud University in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia), the Argonne National Laboratory (U.S.) and the University of California, Berkeley (U.S.).

In their experiments, the physicists allowed laser pulses in the visible range of the spectrum to encounter krypton atoms. The light pulses, with a duration of less than four femtoseconds, in each case ejected an electron from the outer shells of the atoms (a femtosecond is one millionth of one billionth of a second).

Once a laser pulse has knocked an electron out of an atom, the atom becomes a positively charged ion. At the point where the electron has left the atom, a positively charged hole develops inside the ion. Quantum mechanically, this free space then continues to pulsate inside the atom as a so-called quantum beat.

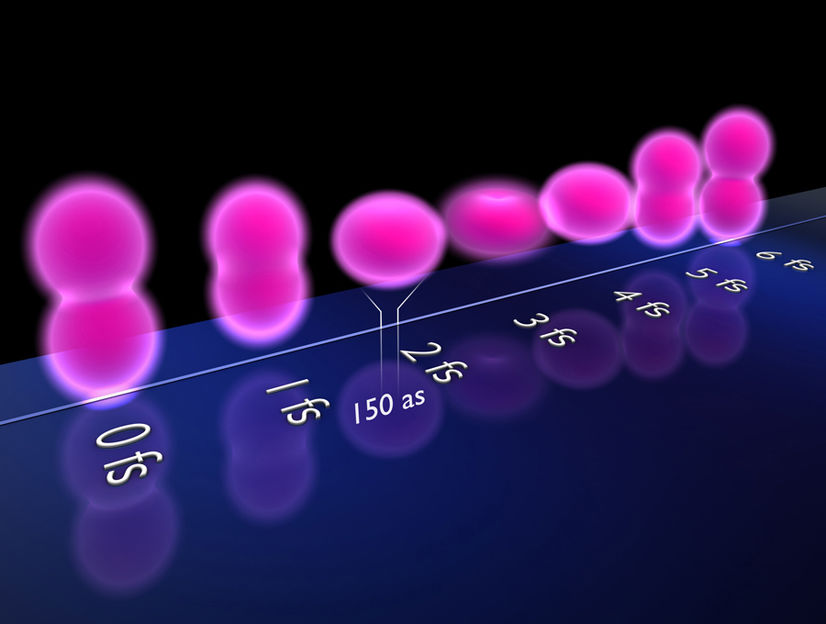

The physicists could now directly observe, and virtually photograph, this pulsation using a second ultraviolet light pulse, lasting only some 150 attoseconds. It turned out that the position of the hole inside the ion, i.e., the positively charged location, moved back and forth between an elongated, club-like shape and a compact, contracted shape, with a cycle period of only around 6 femtoseconds. “Thus, for the first time ever, we succeeded in directly observing the change occurring in the charge distribution inside an atom,” explains Dr. Eleftherios Goulielmakis, research group leader in the team of Prof. Krausz.

“Our experiments have given us a unique real-time view of the micro-cosmos,” explains Ferenc Krausz. “Using attosecond light flashes, we have for the first time recorded quantum- mechanical processes inside an ionised atom.” The findings of the LAP researchers help one to understand the dynamics of elementary particles outside of the atomic nucleus. In more complex (molecular) systems this kind of split-second dynamics is primarily responsible for the sequence of biological and chemical processes. A more precise understanding of this dynamics could in the future lead to a better understanding of the microscopic origin of currently incurable diseases, or to a gradual acceleration in the speed of electronic data processing towards the ultimate limit of electronics. [Thorsten Naeser]

Original publication: Eleftherios Goulielmakis et al.; “Real-time observation of valence electron motion”; Nature, 5. August 2010

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Acetyl_Co-A_synthetase

Copper(II)_sulfate

Malvern Instruments enters distribution partnership with Parsum GmbH

Psorizide_Forte

Jack_Richardson_(chemical_engineer)

Gismondine

Syngenta and Diversa form extensive research and product development alliance

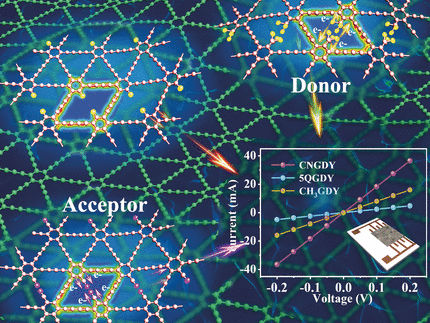

Two-Dimensional Carbon Networks - Graphdiyne as a Functional Lithium-Ion Storage Material