Nanotubes pass acid test

Rice researchers' method untangles long tubes, clears hurdle toward armchair quantum wire

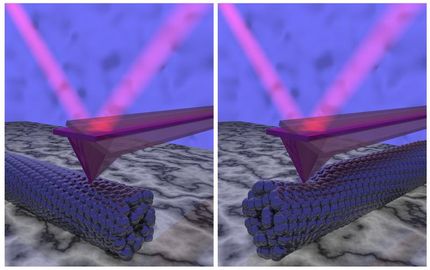

rice University scientists have found the "ultimate" solvent for all kinds of carbon nanotubes (CNTs), a breakthrough that brings the creation of a highly conductive quantum nanowire ever closer. Nanotubes have the frustrating habit of bundling, making them less useful than when they're separated in a solution. Rice scientists led by Matteo Pasquali, a professor in chemical and biomolecular engineering and in chemistry, have been trying to untangle them for years as they look for scalable methods to make exceptionally strong, ultralight, highly conductive materials that could revolutionize power distribution, such as the armchair quantum wire. The armchair quantum wire -- a macroscopic cable of well-aligned metallic nanotubes -- was envisioned by the late Richard Smalley, a Rice chemist who shared the Nobel Prize for his part in discovering the the family of molecules that includes the carbon nanotube. Rice is celebrating the 25th anniversary of that discovery this year. Pasquali, primary author Nicholas Parra-Vasquez and their colleagues reported this month in the online journal ACS Nano that chlorosulfonic acid can dissolve half-millimeter-long nanotubes in solution, a critical step in spinning fibers from ultralong nanotubes. Current methods to dissolve carbon nanotubes, which include surrounding the tubes with soap-like surfactants, doping them with alkali metals or attaching small chemical groups to the sidewalls, disperse nanotubes at relatively low concentrations. These techniques are not ideal for fiber spinning because they damage the properties of the nanotubes, either by attaching small molecules to their surfaces or by shortening them. A few years ago, the Rice researchers discovered that chlorosulfonic acid, a "superacid," adds positive charges to the surface of the nanotubes without damaging them. This causes the nanotubes to spontaneously separate from each other in their natural bundled form. This method is ideal for making nanotube solutions for fiber spinning because it produces fluid dopes that closely resemble those used in industrial spinning of high-performance fibers. Until recently, the researchers thought this dissolution method would be effective only for short single-walled nanotubes. In the new paper, the Rice team reported that the acid dissolution method also works with any type of carbon nanotube, irrespective of length and type, as long as the nanotubes are relatively free of defects. Parra-Vasquez described the process as "very easy." "Just adding the nanotubes to chlorosulfonic acid results in dissolution, without even mixing," he said. While earlier research had focused on single-walled carbon nanotubes, the team discovered chlorosulfonic acid is also adept at dissolving multiwalled nanotubes (MWNTs). "There are many processes that make multiwalled nanotubes at a cheaper cost, and there's a lot of research with them," said Parra-Vasquez, who earned his Rice doctorate last year. "We hope this will open up new areas of research." They also observed for the first time that long SWNTs dispersed by superacid form liquid crystals. "We already knew that with shorter nanotubes, the liquid-crystalline phase is very different from traditional liquid crystals, so liquid crystals formed from ultralong nanotubes should be interesting to study," he said. Parra-Vasquez, now a postdoctoral researcher at Centre de Physique Moleculaire Optique et Hertzienne, Universite' de Bordeaux, Talence, France, came to Rice in 2002 for graduate studies with Pasquali and Smalley. Study co-author Micah Green, assistant professor of chemical engineering at Texas Tech and a former postdoctoral fellow in Pasquali's research group, said working with long nanotubes is key to attaining exceptional properties in fibers because both the mechanical and electrical properties depend on the length of the constituent nanotubes. Pasquali said that using long nanotubes in the fibers should improve their properties on the order of one to two magnitudes, and that similar enhanced properties are also expected in thin films of carbon nanotubes being investigated for flexible electronics applications. An immediate goal for researchers, Parra-Vasquez said, will be to find "large quantities of ultralong single-walled nanotubes with low defects -- and then making that fiber we have been dreaming of making since I arrived at Rice, a dream that Rick Smalley had and that we have all shared since."

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.