Molecules typically found in blue jean and ink dyes may lead to more efficient solar cells

Advertisement

Making better solar cells: Cornell University researchers have discovered a simple process - employing molecules typically used in blue jean and ink dyes - for building an organic framework that could lead to economical, flexible and versatile solar cells. The discovery is reported in the journal Nature chemistry.

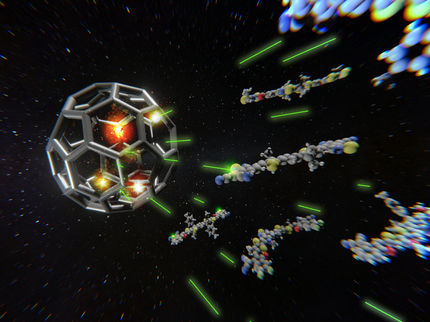

Today's heavy silicon panels are effective, but they can also be expensive and unwieldy. Searching for alternatives, William Dichtel, assistant professor of chemistry and chemical biology, and Eric L. Spitler, a National Science Foundation American Competitiveness in Chemistry Postdoctoral Fellow at Cornell, employed a strategy that uses organic dye molecules assembled into a structure known as a covalent organic framework (COF). Organic materials have long been recognized as having potential to create thin, flexible and low-cost photovoltaic devices, but it has been proven difficult to organize their component molecules reliably into ordered structures likely to maximize device performance.

"We had to develop a completely new way of making the materials in general," Dichtel said. The strategy uses a simple acid catalyst and relatively stable molecules called protected catechols to assemble key organic molecules into a neatly ordered two-dimensional sheet. These sheets stack on top of one another to form a lattice that provides pathways for charge to move through the material.

The reaction is also reversible, allowing for errors in the process to be undone and corrected. "The whole system is constantly forming wrong structures alongside the correct one," Dichtel said, "but the correct structure is the most stable, so eventually, the more perfect structures end up dominating." The result is a structure with high surface area that maintains its precise and predictable molecular ordering over large areas.

The researchers used x-ray diffraction to confirm the material's molecular structure and surface area measurements to determine its porosity.

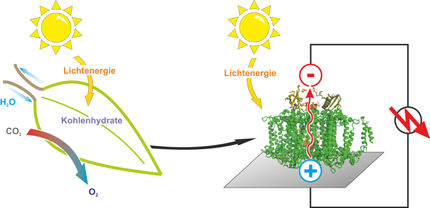

At the core of the framework are molecules called phthalocyanines, a class of common industrial dyes used in products from blue jeans to ink pens. Phthalocyanines are also closely related in structure to chlorophyll, the compound in plants that absorbs sunlight for photosynthesis. The compounds absorb almost the entire solar spectrum – a rare property for a single organic material.

"For most organic materials used for electronics, there's a combination of some design to get the materials to perform well enough, and there's a little bit of an element of luck," Dichtel said. "We're trying to remove as much of that element of luck as we can."

The structure by itself is not a solar cell yet, but it is a model that will significantly broaden the scope of materials that can be used in COFs, Dichtel said. "We also hope to take advantage of their structural precision to answer fundamental scientific questions about moving electrons through organic materials."

Once the framework is assembled, the pores between the molecular latticework could potentially be filled with another organic material to form a light, flexible, highly efficient and easy-to-manufacture solar cell. The next step is to begin testing ways of filling in the gaps with complementary molecules.

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic world Synthesis

Chemical synthesis is at the heart of modern chemistry and enables the targeted production of molecules with specific properties. By combining starting materials in defined reaction conditions, chemists can create a wide range of compounds, from simple molecules to complex active ingredients.

Topic world Synthesis

Chemical synthesis is at the heart of modern chemistry and enables the targeted production of molecules with specific properties. By combining starting materials in defined reaction conditions, chemists can create a wide range of compounds, from simple molecules to complex active ingredients.