Layer by Layer: How simulations help manufacturing of modern displays

Advertisement

Modern materials must be recyclable and sustainable. Consumer electronics is no exception, with organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) taking over modern televisions and portable device displays. However, the development of suitable materials - from the synthesis of molecules to the production of display components - is very time-consuming. Scientists led by Denis Andrienko of the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research and Falk May from Display Solutions at Merck have now developed a simulation method that could significantly speed up the development of new materials.

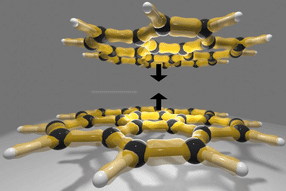

High contrast and low power consumption are key features of innovative organic light-emitting diodes. OLEDs use thin films of organic molecules, i.e. carbon containing molecules, to achieve these goals. Silicon-based materials currently used in other semiconductor devices, such as transistors, may also be replaced by organic counterparts. The challenge here is to tailor the properties of new materials. The trial-and-error approach of synthesizing and depositing thin layers in different combinations is practically not feasible: a typical OLED consists of several individual thin layers, each of which could be made of different materials.

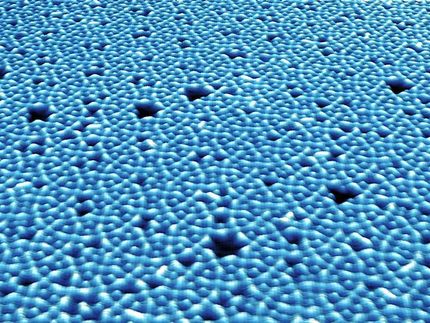

In this situation, computer simulations have proven to be very useful. For example, quantum chemical calculations can predict the electronic properties of individual molecules, before they are synthesized. However, predicting the properties of assemblies of molecules, which is their arrangement in thin films, is still challenging. The complication is that these arrangements depend on the processing conditions, for example the deposition rate, i.e., how many molecules per second land on the film surface. Processing strongly influences how the molecules are arranged relative to each other in the film, how smooth the surface is, what refractive index it has, and so on.

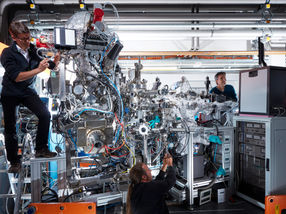

Teams led by Denis Andrienko, a group leader at the MPI for Polymer Research, and Falk May of Merck have now developed a novel approach to predicting the morphologies of organic layers.

The aim was to overcome the computational burden of simulating the deposition process, which in principle would have to take into account every single atom of a molecule. This imposes a maximal timestep in the range of femtoseconds, i.e., millionths of a billionth of a second, which is required to describe molecular motion. The film deposition can, however, take minutes to hours. “Even with today's computing capacities, such a simulation is not feasible” says Denis Andrienko. “We have therefore chosen a different approach: We skip unnecessary details!”. In the models the molecules are not described at an atomic level, but are “coarsened”.

This method, called coarse-graining, speeds up simulations by reducing the friction between coarse-grained molecules, which allows longer times between simulation steps. Now a simulation can be completed in a reasonable time and helps to make predictions about the molecular packing in the film. In experiments, it would take much longer to make and test the individual molecules.

The team, which recently published the results in the journal Advanced Energy Materials, hopes that the simulation technique will accelerate the development of new organic optoelectronic materials.