Nanofibers rid water of hazardous dyes

Waste to purify water - it sounds paradoxical, but that is exactly what has now been achieved

Advertisement

dyes, such as those used in the textile industry, are a major environmental problem. At TU Wien, efficient filters have now been developed – based on cellulose waste.

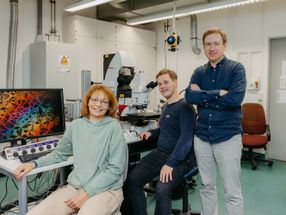

Günther Rupprechter and Qaisar Maqbool with a visualization of the nano web.

Vienna University of Technology

Using waste to purify water may sound counterintuitive. But at TU Wien, this is exactly what has now been achieved: a special nanostructure has been developed to filter a widespread class of harmful dyes from water. A crucial component is a material that is considered waste: used cellulose, for example in the form of cleaning cloths or paper cups. The cellulose is utilized to coat a fine nano-fabric to create an efficient filter for polluted water.

Colored poison in the water

Organic dyes represent the largest group of synthetic dyes, including so-called azo compounds. They are widely used in the textile industry, even in countries where little attention is paid to environmental protection, and the dyes often end up in unfiltered wastewater. "This is dangerous because such dyes degrade very slowly, they can remain in the water for a long time and pose great danger to humans and nature," says Prof. Günther Rupprechter from the Institute of Materials Chemistry at TU Wien.

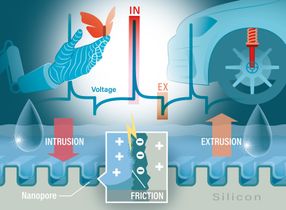

There are various materials that can bind such dyes. But that alone is not enough. "If you simply let the polluted water flow over a filter film that can bind dyes, the cleaning effect is low," explains Günther Rupprechter. "It's much better to create a nanofabric out of lots of tiny fibers and let the water seep through." The water then comes into contact with a much larger surface area, and thus many more organic dye molecules can be bound.

Cellulose waste as a nano-filter

"We are working with semi-crystalline nanocellulose, which can be produced from waste material," says Qaisar Maqbool, first author of the study and postdoc in Rupprechter's research group. "Metal-containing substances are often used for similar purposes. Our material, on the other hand, is completely harmless to the environment, and we can also produce it by upcycling waste paper."

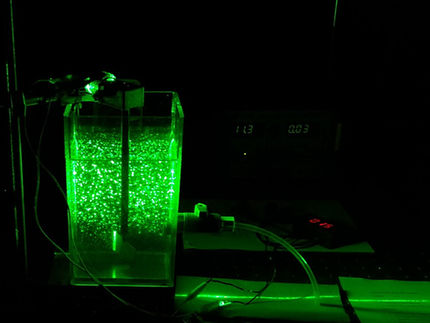

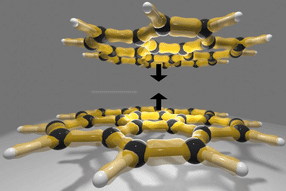

This nano-cellulose is "spun" together with the plastic polyacrylonitrile into nanostructures. However, this requires a lot of technical skill. The team from the TU Wien was successful with a so-called electrospinning process. In this process, the material is sprayed in liquid form, the droplets are electrically charged and sent through an electric field.

"This ensures that the liquid forms extremely fine threads with a diameter of 180 to 200 nanometers during curing," says Günther Rupprechter. These threads form a fine tissue with a high surface area - a so-called "nanoweb". A network of threads can be placed on one square centimeter, with a total surface area of more than 10 cm2 .

Successful tests

The tests with these cellulose-coated nanostructures were very successful: In three cycles, water contaminated with violet dye was purified, and 95% of the dye was removed. "The dyes remain stored in the nanoweb. You can then either dispose of the entire web or regenerate it, dissolve the stored dyes and reuse the filter fabric," explains Günther Rupprechter.

However, more work needs to be done: evaluating the mechanical properties of the sophisticated nanowebs, conducting biocompatibility tests, assessing sensitivity to more complex pollutants, and achieving scalability to industrial-grade standards. Now Rupprechter and his research team want to investigate how this dye filter technology can be transferred to other areas of application. "This technology could also be very interesting for the medical field," Rupprechter believes. "Dialysis, for example, also needs filtering out very specific chemical substances from a liquid." Coated nanofabrics may be useful for such applications.