When heat turns into electricity at 1000 °C

New perspectives for producing electricity from industrial waste heat

Together with the Technical University of Hamburg and Aalborg University, researchers from the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon have developed a new selective emitter based on iridium for thermophotovoltaics. Iridium was thus used for the first time as a material for an emitter, and in the experiments, it showed particular endurance at high temperatures around 1000 °C. Their study results were published in the journal Advanced Materials and open up new perspectives for producing electricity from heat.

The conversion of heat into electricity is the principle of thermophotovoltaics. To make the heat efficiently usable in the form of radiant energy, so-called selective emitters are needed. They sit between the heat source and the photovoltaic cell and emit only a certain part of the radiation while suppressing the other. The challenge here is that the conversion of heat into electricity takes place at high temperatures around 1000°C - the emitter must therefore be able to withstand these temperatures without losing the accuracy of its selectivity. In cooperation with the Technical University of Hamburg (TUHH) and Aalborg University, researchers at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon have now succeeded in producing a new emitter based on the resistant metal iridium that can withstand these conditions without losing its effectiveness.

"With iridium, we address both aspects at the same time: selectivity and temperature stability," says Alexander Petrov, who works on optical properties of materials at TUHH. "Selective emitters based on iridium are very good at suppressing unwanted radiation and do not react with oxygen. Iridium is a precious metal like gold, but suitable for high-temperature applications."

"By avoiding the adverse effects of oxidation, we have unlocked the potential for more efficient and sustainable systems." reports Gnanavel Vaidhyanathan Krishnamurthy, lead author of the study and a scientist at the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon. "This innovation opens the doors to new possibilities in waste heat recovery, solar thermal power generation and beyond."

The emitter's function

In thermophotovoltaics, as in photovoltaics, radiant energy is converted into electricity by a photovoltaic cell. However, in thermophotovoltaics the radiant energy does not come from the sun, but from a heat source, such as is used in the steel industry. The emitter is located between the heat source and the solar cell. It consists of several very thin layers (metal and oxide alternately), which should remain unchanged at high temperatures to enable heat to be converted into electricity. For this purpose, it ideally emits only short-wave photons and suppresses long-wave ones - it thus has a selective effect. This is important because the photovoltaic cell is not able to convert the long-wave radiation into electricity. At high temperatures, however, most metals oxidise and the function of the emitter fails. As the researchers were able to show, the newly developed selective emitter made of iridium and hafnium oxide retains its function completely over 100 hours at 1000 °C - the metal withstands the demanding challenges without any losses, as the researchers were able to show through X-ray examinations. The successful development of selective emitters based on iridium is an important step towards the further development of thermophotovoltaics.

In the transition to renewable energy, securing a constant power supply is of great importance. Thermophotovoltaics could not only generate electricity from industrial waste heat, but also make an important contribution to the conversion of the energy supply to renewable energies. Here, the energy generated by photovoltaics and wind turbines, which naturally fluctuates over time, is temporarily stored in heat reservoirs in order to extract it again later - when the sun is not shining or the wind is not blowing - and convert it into electrical energy, which is then continuously available, by means of thermophotovoltaics, and in this way stabilise the energy grids.

Original publication

Gnanavel Vaidhyanathan Krishnamurthy, Manohar Chirumamilla, Tobias Krekeler, Martin Ritter, Ragle Raudsepp, Mauricio Schieda, Thomas Klassen, Kjeld Pedersen, Alexander Yu. Petrov, Manfred Eich, Michael Störmer; "Iridium‐Based Selective Emitters for Thermophotovoltaic Applications"; Advanced Materials, 2023-9-8

Most read news

Original publication

Gnanavel Vaidhyanathan Krishnamurthy, Manohar Chirumamilla, Tobias Krekeler, Martin Ritter, Ragle Raudsepp, Mauricio Schieda, Thomas Klassen, Kjeld Pedersen, Alexander Yu. Petrov, Manfred Eich, Michael Störmer; "Iridium‐Based Selective Emitters for Thermophotovoltaic Applications"; Advanced Materials, 2023-9-8

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

List_of_drugs:_Df-Di

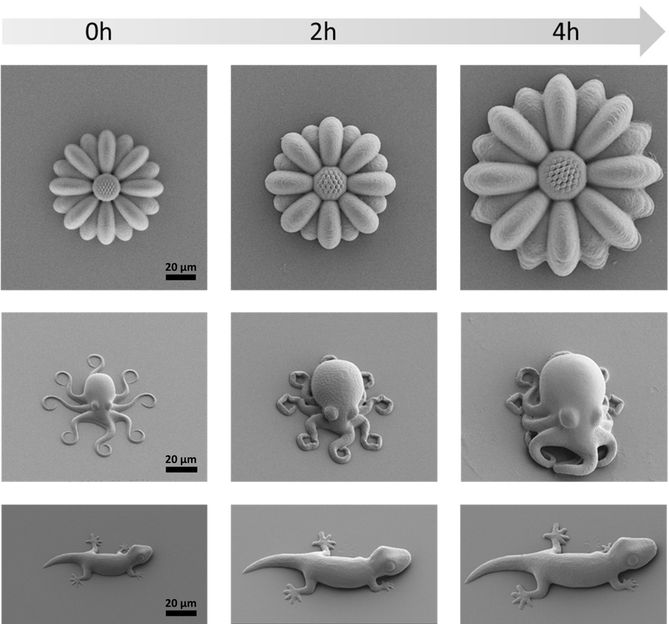

Microscopic Octopuses from a 3D Printer - Newly developed smart polymers have “life-like” properties

GRYF HB spol. s.r.o - Havlíčkův Brod, Czechia

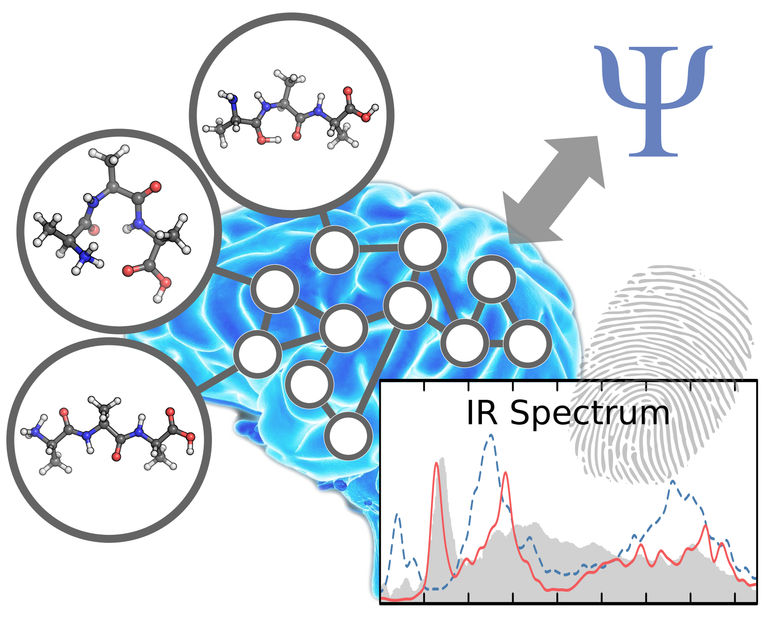

Artificial intelligence for obtaining chemical fingerprints - Neural networks carry out chemical simulations in record time