Researchers finds a new method for recycling polystyrene

This method would create an incentive for polystyrene to be collected and recycled instead of going into landfills

Ocean trash and overflowing landfills have drawn widespread attention to the plastic waste that we put into our environment. In response, communities around the world work hard to reduce, reuse, and recycle. But what does it mean for something to be recyclable? A research team led by Guoliang "Greg" Liu, associate professor of chemistry in the College of Science, is working to expand the frontiers of plastic recycling.

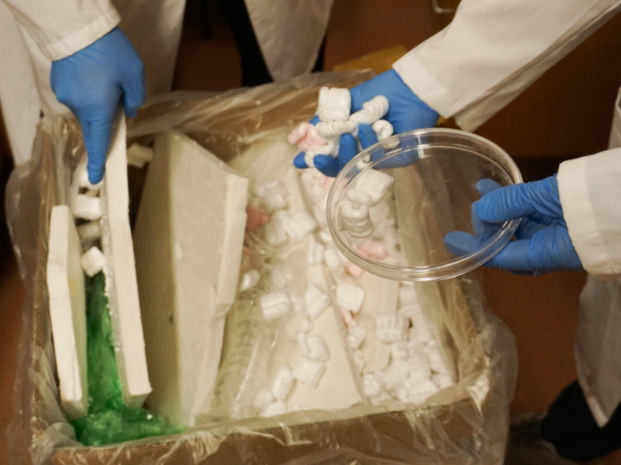

Researchers sort through various objects made from polystyrene, a type of plastic that is rarely recycled. Photo by Reilly Henson for Virginia Tech.

Virginia Tech

Many of us are comfortable tossing a metal can or a glass jar into the recycling bin without a second thought. But plastics are a bit different. Not every recycling plant is equipped to handle every type of plastic. That’s because the chemistry and structure of plastic materials are diverse, and each type requires a specific recycling procedure.

In a perfect world, perhaps there would be recycling plants all over the world equipped to handle every kind of plastic imaginable. But we’re not there yet, due in part to the fact that some plastics are very difficult to recycle, and we have yet to develop effective, practical techniques for processing them.

Polystyrene is one such challenging material. Best known as a major component in Styrofoam, polystyrene is widely used but rarely recycled. Many municipal recycling facilities instruct residents (including those in Blacksburg) not to put polystyrene in their home recycling bins.

Currently, the main method for recycling polystyrene yields a product that is often too low-quality to make the process economically viable. In other words, if a recycling plant tries to recycle polystyrene on a large scale, it will either need a financial boost, such as a government subsidy, or the operation risks running out of money and shutting down.

One solution to this problem is to improve the recycling process so that it becomes economically viable, or even better, economically attractive. With his experience in polymer chemistry and as an affiliate of the Macromolecules Innovation Institute, this is exactly what Liu was able to guide his team to do.

In a paper recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team presents a new method for recycling — or perhaps more accurately, “upcycling” — polystyrene. By exposing the material to ultraviolet light and adding a chemical catalyst, this method creates a product called diphenylmethane (DPM) that is immensely useful. DPM is used as a precursor in drug development, polymer manufacturing, and even as a fragrance in consumer products. Importantly, DPM has a market price that is 10 times higher than other materials that can currently be made from recycled polystyrene.

The researchers took their investigation one step further: They wanted to confirm that this new method would achieve the economic viability they were striving for. The chemists from Virginia Tech teamed up with business experts from Santa Clara University and the Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, who ran an analysis to determine how profitable the recycling method would be overall. Their results showed that because DPM has such a high economic value, the costs of collecting and processing the polystyrene would be fully justified.

This new recycling method would create an incentive for polystyrene to be collected and recycled instead of going into landfills or becoming plastic pollution.

“I think it’s important for people to realize that big global challenges like plastic waste can have — and most likely demand — multiple solutions,” said Liu. “We at Virginia Tech can contribute a small piece to the big puzzle and offer solutions to positively impact the world.”