Just add water: A simple method to obtain versatile porous polymers

Scientists discover they can produce polyethylenimine-based network polymers by simply dissolving triaziridine compounds in water

For a polymer composed of very simple repeating units, polyethylenimine (PEI) has an astounding number of practical applications, including detergents, adhesives, cosmetics, industrial agents, CO2 capture, and even cellular cultures. In general, PEI is synthesized by the ring-opening polymerization of ethylenimine, also known as aziridine. When produced this way, the result is a liquid polymer with a branching structure.

Researchers from SIT, Japan, discover that adding water to a triaziridine compound at mild temperatures is enough to produce strong and consistent porous polymers. By adjusting the reaction temperature and the initial triaziridine concentration, the morphological and mechanical characteristics of the polymers can be controlled.

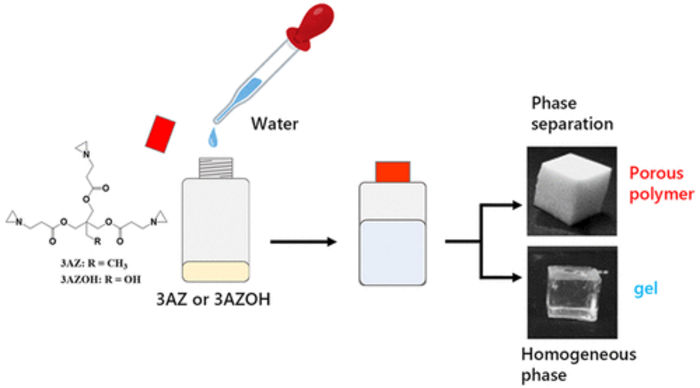

Reprinted (adapted) with permission from Naga et al. Ring-Opening Polymerization of Triaziridine Compounds in Water: An Extremely Facile Method to Synthesize a Porous Polymer through Polymerization-Induced Phase Separation. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 5, 603–607. Copyright {2022} American Chemical Society.

Despite its huge potential, PEI is held back by the fact that ethylenimine is a highly toxic substance. Because this precursor is commercially unavailable, it is rather difficult to conduct experiments aimed at controlling the morphology or state of PEI. As a consequence, we might be missing out on many new applications for PEI.

To tackle this problem, a research team from Shibaura Institute of Technology (SIT), Japan, has focused on developing new PEI-based network polymers. Led by Professor Naofumi Naga of the Graduate School of Engineering and Science at SIT, this team recently discovered a simple, yet revolutionary way to produce such polymers starting from a triaziridine compound; their suggestion—just add some water. This study, made available online on 12 April 2022 and subsequently published in volume 11 issue 5 of ACS Macro Letters on 17 May 2022, was done in collaboration with Professor Tamaki Nakano of the Institute for Catalysis and Graduate School of Chemical Sciences and Engineering, at Hokkaido University, Japan, through the Joint Usage/Research Center Program (MEXT).

Though the researchers tested two triaziridine compounds, only one of them could consistently yield a porous polymer network after reacting with water. Its complete chemical name is 2,2-bishydroxymethylbutanol-tris[3-(1-aziridinyl)propionate] and it can be abbreviated as ‘3AZ.’ The team discovered that dissolving 3AZ in distilled water at temperatures in the modest range of 20 to 50 °C was enough to open up the aziridine groups and cause the 3AZ monomers to link with each other. The result, under most temperatures and initial 3AZ concentrations, was a porous polymer phase.

The team analyzed the morphology of the porous polymers via scanning electron microscopy. While the synthesis temperature seemed to play no role in this regard, different concentrations of 3AZ resulted in different particle sizes, ranging from 1 to 5 μm. On the contrary, the synthesis temperature did affect some of the mechanical properties of the porous polymers, such as their Young’s (elasticity) modulus. Notably, all the porous polymers could withstand compression tests of 50 N.

Being able to tailor the morphological and mechanical characteristics of PEI-based porous polymers is a big advantage, even more so when all that’s needed is adjusting a simple reaction with water. “Water is an ideal solvent for chemistry because of its eco-friendliness, availability, and sustainability,” remarks Professor Naga, “Our paper reports one of the easiest methods to obtain a PEI-based network polymer known to date.” In addition to the versatile properties, the team found that their porous polymers could absorb various solvents irrespective of their characteristics, including hexane, acetone, ethanol, dichloromethane, and chloroform.

Overall, this study will hopefully bring novel PEI-based polymers to the limelight. With eyes set on the future, Professor Naga and colleagues expect to find new uses for these compounds. “Processing and chemical modification of the 3AZ porous polymers will likely expand their fields of application, and investigations on these aspects are already underway,” he concludes.