Light amplification accelerates chemical reactions in aerosols

Temporal sequence of photochemical reaction in individual aerosol particles observed with high resolution

aerosols in the atmosphere react to incident sunlight. This light is amplified in the interior of the aerosol droplets and particles, accelerating reactions. ETH researchers have now been able to demonstrate and quantify this effect and recommend factoring it into future climate models.

The Saharan dust that coloured skies in mid-March was made up of mineral aerosols. But even outside of such extreme events, there are aerosols composed of mineral and organic compounds in the air.

Unsplash

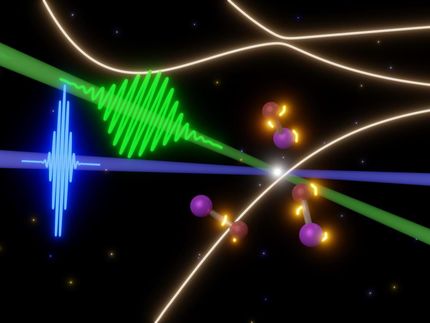

Liquid droplets and very fine particles can trap light – similar to how light can be caught between two mirrors. As a result, the intensity of the light inside them is amplified. This also happens in very fine water droplets and solid particles in our atmosphere, i.e. aerosols. Using modern X-ray microscopy, chemists at ETH Zurich and the Paul Scherrer Institute (PSI) have now investigated how light amplification affects photochemical processes that take place in the aerosols. They were able to demonstrate that light amplification causes these chemical processes to be two to three times faster on average than they would be without this effect.

Using the Swiss Light Source at the PSI, the researchers studied aerosols consisting of tiny particles of iron(III) citrate. Exposure to light reduces this compound to iron(II) citrate. X-ray microscopy makes it possible to distinguish areas within the aerosol particles composed of iron(III) citrate from those made up of iron(II) citrate down to a precision of 25 nanometres. In this way, the scientists were able to observe and map in high resolution the temporal sequence of this photochemical reaction in individual aerosol particles.

Decay upon exposure to light

“For us, iron(III) citrate was a representative compound that was easy to study with our method,” says Pablo Corral Arroyo, a postdoc in the group headed by ETH Professor Ruth Signorell and a lead author of the study. Iron(III) citrate stands in for a whole range of other chemical compounds that can occur in the aerosols of the atmosphere. Many organic and inorganic compounds are light-sensitive, and when exposed to light, they can break down into smaller molecules, which can be gaseous and therefore escape. “The aerosol particles lose mass in this way, changing their properties,” Signorell explains. Among other things, they scatter sunlight differently, which affects weather and climate phenomena. In addition, their characteristics as condensation nuclei in cloud formation change.

As such, the results also have an effect on climate research. “Current computer models of global atmospheric chemistry don’t yet take this light amplification effect into account,” ETH Professor Signorell says. The researchers suggest incorporating the effect into these models in future.

Non-uniform reaction times in the particles

Now precisely mapped and quantified, the light amplification in the particles comes about through resonance effects. The light intensity is greatest on the side of the particle opposite the one the light is shining on. “In this hotspot, photochemical reactions are up to ten times faster than they would be without the resonance effect,” says Corral Arroyo. Averaged over the entire particle, this gives an acceleration by the above-mentioned factor of two to three. Photochemical reactions in the atmosphere usually last several hours or even days.

Using the data from their experiment, the researchers were able to create a computer model to estimate the effect on a range of other photochemical reactions of typical aerosols in the atmosphere. It turned out that the effect does not pertain just to iron(III) citrate particles, but all aerosols – particles or droplets – made of compounds that can react with light. And these reactions are also two to three times faster on average.

Original publication

Original publication

Corral Arroyo P, David G, Alpert PA, Parmentier EA, Ammann M, Signorell R: Amplification of light within aerosol particles accelerates in-particle photochemistry, Science, 14. April 2022

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.