Breakthrough in making nanocrystals function together electronically

Conductive supercrystals for next-generation electronic technology

Advertisement

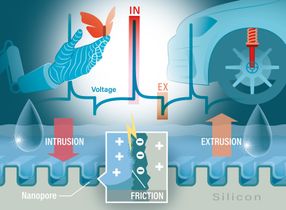

A new study of an international team of chemists introduces a breakthrough in making nanocrystals function together electronically. Published March 25 in the journal “Science”, the research may open the doors to future devices, such as next-generation displays or solar cells.

You can carry an entire computer in your pocket today because the technological building blocks have been getting smaller and smaller since the 1950s. But in order to create future generations of electronics, scientists will need to come up with entirely new technology at the tiniest scales.

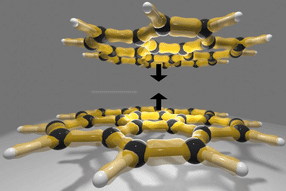

pixabay.com

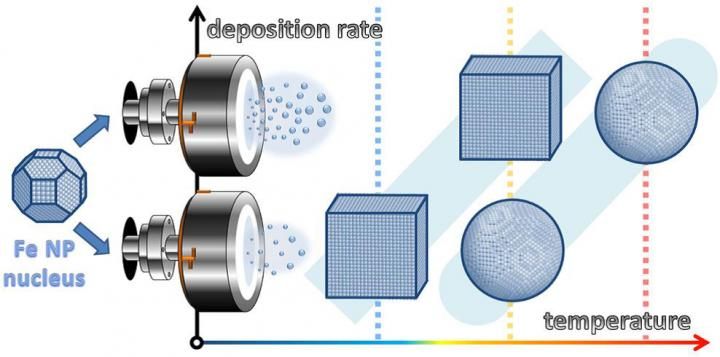

Nanocrystals are some of the most promising building blocks of future technology, such as powerful phones, more efficient solar cells, or even quantum computers. Scientists can grow nanocrystals out of many different materials: metals, semiconductors, and magnets, each material yields different properties. Moreover, these tiny crystals can assemble themselves into highly-ordered, well-facetted and beautiful supercrystals. However, the trouble is that whenever scientists tried to assemble the nanocystals together into arrays, the new supercrystals would grow with long “hairs” around them: long-chained organic molecules. These organic ligands make it difficult for electrons to jump from one nanocrystal to another and thus, rendering the superstructures useless for most applications in electronics and sensing. Therefore the researchers needed a method to reduce the “hairs” around each nanocrystal, so they could pack them in more tightly and reduce the gaps in between.

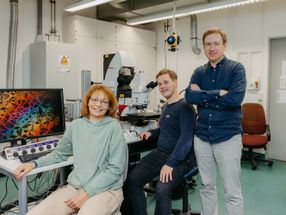

In 2015, a new group of all-inorganic ligands emerged, which provided stability and maintained electrical conductivity. “Back then I thought that these new ligands might be the best chance to finally close the gap between superstructures and their use for electrical applications,” remembers Danny Haubold, PhD student in Physical Chemistry at TU Dresden at that time. Self-assembling of charge stabilized nanoparticles is quite a challenge. Everything has to be fine-tuned in order to achieve the desired supercrystals. So, he and Prof. Alexander Eychmüller started to cooperate with the group of Dmitri Talapin at the University of Chicago, which developed these new ligands. Together they performed the very first experiments with remarkable results proving that the problem is challenging, but achievable.

“After six years of intensive research and cooperation between multiple institutions, it has been proven that, following this route, a very broad range of materials and sizes can be assembled into highly-ordered, but also highly conductive supercrystals. This opens up the doors to a new class of materials. The promising results of the first experiments have been successfully transferred to a broad range of materials, such as gold, platinum, nickel, lead sulfide, and lead selenide. Using small- and wide-angle x-ray scattering and strong input from theory, the superlattice structures have been characterized forming the basis for an in-depth analysis and manipulation of their formation mechanism,” explains Prof. Alexander Eychmüller.

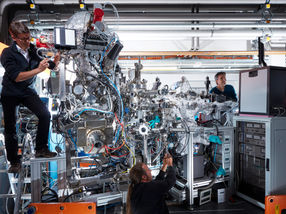

The study included scientists with the University of Chicago, Technische Universität Dresden, Northwestern University, Arizona State University, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and the University of California, Berkeley.

Original publication

Coropceanu I, Janke EM, Portner J, Haubold D, Nguyen TD, Das A, Tanner CPN, Utterback JK, Teitelbaum SW, Hudson MH, Sarma NA, Hinkle AM, Tassone CJ, Eychmüller A, Limmer DT, Olvera de la Cruz M, Ginsberg NS, Talapin DV. Self-assembly of nanocrystals into strongly electronically coupled all-inorganic supercrystals. Science. 2022 Mar 25;375(6587):1422-1426.