Protons are probably actually smaller than long thought

Study suggests errors in the interpretation of older measurements

A few years ago, a novel measurement technique showed that protons are probably smaller than had been assumed since the 1990s. This surprised the scientific community; some researchers even believed that the Standard Model of particle physics would have to be changed. Physicists at the University of Bonn and the TU Darmstadt have now developed a method that allows them to analyze the results of older and more recent experiments much more comprehensively than before. This also results in a smaller proton radius from the older data. So there is probably no difference between the values - no matter which measurement method they are based on.

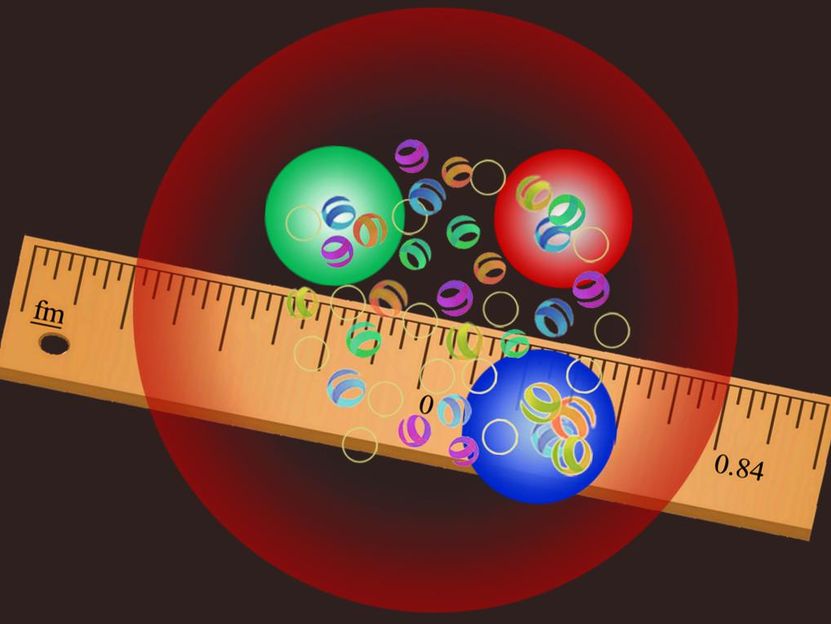

The proton (red) - has a radius of 0.84 femtometers (fm). Also shown in the figure are the three quarks that make up the proton and the gluons that hold them together.

© Figure: Dr. Yong-Hui Lin/University of Bonn

Our office chair, the air we breathe, the stars in the night sky: they are all made of atoms, which in turn are composed of electrons, protons and neutrons. Electrons are negatively charged; according to current knowledge, they have no expansion, but are point-like. The positively charged protons are different - according to current measurements, their radius is 0.84 femtometers (a femtometer is a quadrillionth of a meter).

Until a few years ago, however, they were thought to be 0.88 femtometers - a tiny difference that caused quite a stir among experts. Because it was not so easy to explain. Some experts even considered it to be an indication that the Standard Model of particle physics was wrong and needed to be modified. "However, our analyses indicate that this difference between the old and new measured values does not exist at all," explains Prof. Dr. Ulf Meißner from the Helmholtz Institute for Radiation and Nuclear Physics at the University of Bonn. "Instead, the older values were subject to a systematic error that has been significantly underestimated so far."

Playing billiards in the particle cosmos

To determine the radius of a proton, one can bombard it with an electron beam in an accelerator. When an electron collides with the proton, both change their direction of motion - similar to the collision of two billiard balls. In physics, this process is called elastic scattering. The larger the proton, the more frequently such collisions occur. Its expansion can therefore be calculated from the type and extent of the scattering.

The higher the velocity of the electron beam, the more precise the measurements. However, this also increases the risk that the electron and proton will form new particles when they collide. "At high velocities or energies, this happens more and more often," explains Meißner, who is also a member of the Transdisciplinary Research Areas "Mathematics, Modeling and Simulation of Complex Systems" and "Building Blocks of Matter and Fundamental Interactions." "In turn, the elastic scattering events are becoming rarer. Therefore, for measurements of the proton size, one has so far only used accelerator data in which the electrons had a relatively low energy."

In principle, however, collisions that produce other particles also provide important insights into the shape of the proton. The same is true for another phenomenon that occurs at high electron beam velocities - so-called electron-positron annihilation. "We have developed a theoretical basis with which such events can also be used to calculate the proton radius," says Prof. Dr. Hans-Werner Hammer of TU Darmstadt. "This allows us to take into account data that have so far been left out."

Five percent smaller than assumed 20 years

Using this method, the physicists reanalyzed readings from older, as well as very recent, experiments - including those that previously suggested a value of 0.88 femtometers. With their method, however, the researchers arrived at 0.84 femtometers; this is the radius that was also found in new measurements based on a completely different methodology.

So the proton actually appears to be about 5 percent smaller than was assumed in the 1990s and 2000s. At the same time, the researchers' method also allows new insights into the fine structure of protons and their uncharged siblings, neutrons. So it's helping us to understand a little better the structure of the world around us - the chair, the air, but also the stars in the night sky.