Corals remove microplastics from ocean waters

"Corals are the first organisms to be discovered as a living sink for microplastics in the ocean"

Reef-building corals permanently incorporate small plastic particles into their calcium carbonate skeleton – study in marine aquaria of the University of Giessen provides first evidence of organisms that remove microplastics from the environment in the long term

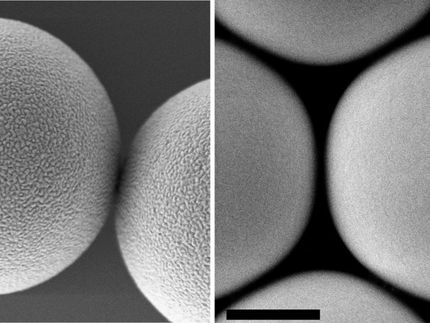

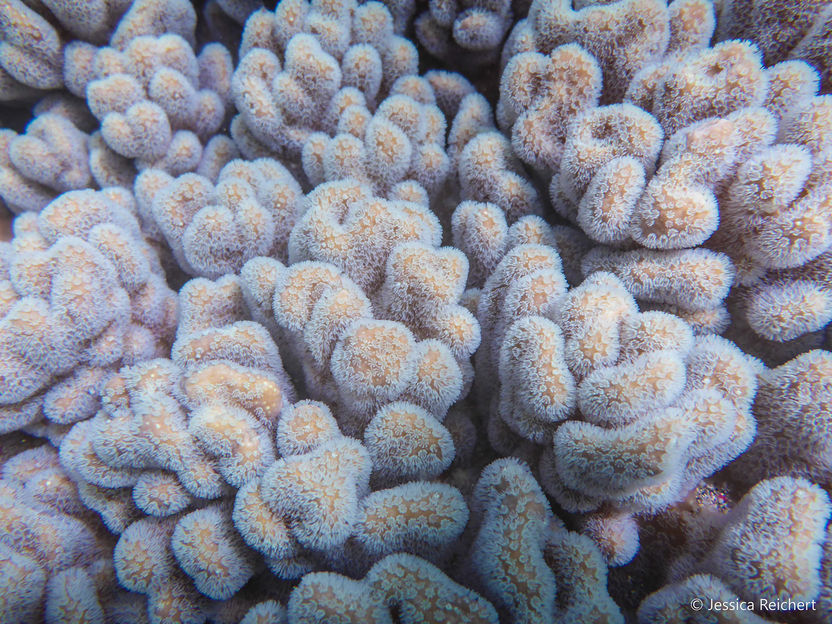

Storage site for microplastics: stony corals.

Jessica Reichert

A coral has incorporated microplastics (black particles) into its skeleton.

Jessica Reichert

Increasing numbers of tiny particles of plastic, known as microplastics, can be found in the world's oceans. Where these waste particles from car tires, diapers, decaying plastic bags and other every day products are deposited in the long term is not conclusively understood. So far, non-living storage sites such as Arctic ice, sediments in coastal areas and the deep sea have been identified. Researchers at Justus Liebig University Giessen (JLU) currently found now that living organisms are able to store microplastics permanently as well. According to their study, corals actively absorb microplastics and incorporate particles into their calcium carbonate skeleton. In this way, reef-building organisms contribute to the decontamination of seawater. The study was published in the journal Global Change Biology.

"Corals are the first organisms to be discovered as a living sink for microplastics in the ocean," said Dr. Jessica Reichert, JLU coral researcher and lead author of the study. The organisms could trap up to 20,000 tons of microplastics a year in coral reefs worldwide, she and her team estimate. That is about one percent of the microplastics present in reef waters – just for this one group of animals. Dr. Reichert says: "Our study sheds new light on coral reefs. They help maintaining the ecological balance of the oceans and serve as long-term repositories for microplastics."

For the study, Reichert and her team examined four coral species native to the Indo-Pacific, where about 90 percent of all coral reefs are located: staghorn corals, cauliflower corals, hump corals and blue corals. In the Giessen seawater aquariums, they simulated microplastic pollution over 18 months. The team observed under the microscope how the animals absorb these tiny particles, which are about 100 micrometers in size. Analyses of tissue and skeletons from 54 corals provided precise data. They found that corals store up to 84 microplastic particles per cubic centimeter in their bodies – primarily in their skeleton, but also in their tissue. One coral, for example, absorbed up to 600 microplastic particles while doubling its body size from five to ten centimeters.

But how do the tiny plastic particles get into the skeleton? Corals feed on plankton, which they filter out of the water using specialized cells. During the process, other small particles may also be ingested. "The coral normally recognizes inedible particles," says Dr. Reichert. "However, they seem to have a problem identifying microplastics. Many particles are accidentally ingested and some end up in the skeleton."

Even if the permanent ingestion of microplastics seems to have a positive effect on marine ecosystems, it can be dangerous for the coral and entire reef systems. In 2019, the Giessen team, together with researchers from Australia, found that some coral species grow less or even become sick when exposed to microplastics, for example, showing coral bleaching. The current study adds a new piece to the puzzle.

"We do not know what the consequences of microplastic deposition might be for coral organisms,” Dr. Reichert says. “It might affect reef stability and integrity and could pose another threat to coral reefs worldwide, which are already endangered by climate change.”

The study was conducted as part of the "Ocean 2100" project of the German-Colombian Center of Excellence in Marine Sciences (CEMarin) and funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD). In the "Ocean 2100" seawater aquarium facility in Giessen, researchers simulate the human impact on coral reefs, such as climate change and microplastic pollution.