How sugar-loving microbes could help power future cars

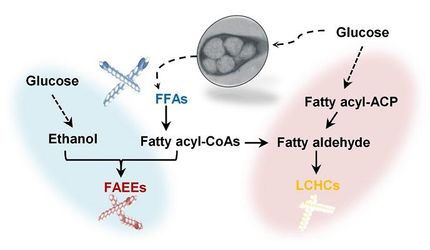

Genetically engineered E. coli eat glucose, then help turn it into molecules found in gasoline

Advertisement

It sounds like modern-day alchemy: Transforming sugar into hydrocarbons found in gasoline. But that’s exactly what scientists have done.

Zhen Wang, University at Buffalo assistant professor of biological sciences, holds a flask containing a strain of E. coli that doesn’t endanger human health. Wang and colleagues have shown that genetically engineered E. coli can convert glucose into a class of fatty acids, which can then be transformed into hydrocarbons called olefins.

Douglas Levere / University at Buffalo

In a study in Nature Chemistry, researchers report harnessing the wonders of biology and chemistry to turn glucose (a type of sugar) into olefins (a type of hydrocarbon, and one of several types of molecules that make up gasoline).

The project was led by biochemists Zhen Q. Wang at the University at Buffalo and Michelle C. Y. Chang at the University of California, Berkeley.

The paper marks an advance in efforts to create sustainable biofuels.

Olefins comprise a small percentage of the molecules in gasoline as it’s currently produced, but the process the team developed could likely be adjusted in the future to generate other types of hydrocarbons as well, including some of the other components of gasoline, Wang says. She also notes that olefins have non-fuel applications, as they are used in industrial lubricants and as precursors for making plastics.

A two-step process using sugar-eating microbes and a catalyst

To complete the study, the researchers began by feeding glucose to strains of E. coli that don’t pose a danger to human health.

“These microbes are sugar junkies, even worse than our kids,” Wang jokes.

The E. coli in the experiments were genetically engineered to produce a suite of four enzymes that convert glucose into compounds called 3-hydroxy fatty acids. As the bacteria consumed the glucose, they also started to make the fatty acids.

To complete the transformation, the team used a catalyst called niobium pentoxide (Nb2O5) to chop off unwanted parts of the fatty acids in a chemical process, generating the final product: the olefins.

The scientists identified the enzymes and catalyst through trial and error, testing different molecules with properties that lent themselves to the tasks at hand.

“We combined what biology can do the best with what chemistry can do the best, and we put them together to create this two-step process,” says Wang, PhD, an assistant professor of biological sciences in the UB College of Arts and Sciences. “Using this method, we were able to make olefins directly from glucose.”

Glucose comes from photosynthesis, which pulls CO2 out of the air

“Making biofuels from renewable resources like glucose has great potential to advance green energy technology,” Wang says.

“Glucose is produced by plants through photosynthesis, which turns carbon dioxide (CO2) and water into oxygen and sugar. So the carbon in the glucose — and later the olefins — is actually from carbon dioxide that has been pulled out of the atmosphere,” Wang explains.

More research is needed, however, to understand the benefits of the new method and whether it can be scaled up efficiently for making biofuels or for other purposes. One of the first questions that will need to be answered is how much energy the process of producing the olefins consumes; if the energy cost is too high, the technology would need to be optimized to be practical on an industrial scale.

Scientists are also interested in increasing the yield. Currently, it takes 100 glucose molecules to produce about 8 olefin molecules, Wang says. She would like to improve that ratio, with a focus on coaxing the E. coli to produce more of the 3-hydroxy fatty acids for every gram of glucose consumed.