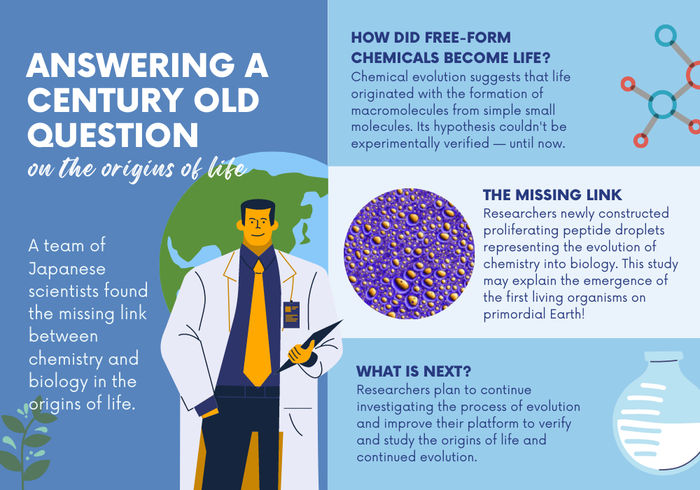

Answering a century-old question on the origins of life

A team of Japanese scientists found the missing link between chemistry and biology in the origins of life

The missing link isn’t a not-yet-discovered fossil, after all. It’s a tiny, self-replicating globule called a coacervate droplet, developed by two researchers in Japan to represent the evolution of chemistry into biology.

A team of Japanese scientists found the missing link between chemistry and biology in the origins of life.

Hiroshima University

“Chemical evolution was first proposed in the 1920s as the idea that life first originated with the formation of macromolecules from simple small molecules, and those macromolecules formed molecular assemblies that could proliferate,” said first-author Muneyuki Matsuo, assistant professor of chemistry in the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life at Hiroshima University. “Since then, many studies have been conducted to verify the RNA world hypothesis — where only self-replicating genetic material existed prior to the evolution of DNA and proteins — experimentally. However, the origin of molecular assemblies that proliferate from small molecules has remained a mystery for about a hundred years since the advent of the chemical evolution scenario. It has been the missing link between chemistry and biology in the origin of life.”

Matsuo partnered with Kensuke Kurihara, researcher at KYOCERA Corporation, to answer the century-old question: how did the free-form chemicals of early Earth become life? Like many researchers, they initially thought it came down to the environment: the ingredients formed under high pressure and temperature, then cooled into more life-friendly conditions. The issue was propagation.

“Proliferation requires spontaneous polymer production and self-assembly under the same conditions,” Matsuo said.

They designed and synthesized a new prebiotic monomer from amino acid derivatives as a precursor to the self-assembly of primitive cells. When added to room temperature water at atmospheric pressure, the amino acid derivatives condensed, arranging into peptides, which then spontaneously formed droplets. The droplets grew in size and in number when fed with more amino acids. The researchers also found that the droplets could concentrate nucleic acids — genetic material — and they were more likely to survive against external stimuli if they exhibited this function.

“A droplet-based protocell could have served as a link between ‘chemistry’ and ‘biology’ during the origins of life,” Matsuo said. “This study may serve to explain the emergence of the first living organisms on primordial Earth.”

The researchers plan to continue investigating the process of evolution from amino acid derivatives to primitive living cells, as well as improve their platform to verify and study the origins of life and continued evolution.

“By constructing peptide droplets that proliferate with feeding on novel amino acid derivatives, we have experimentally elucidated the long-standing mystery of how prebiotic ancestors were able to proliferate and survive by selectively concentrating prebiotic chemicals,” Matsuo said. “Rather than an RNA world, we found that ‘droplet world’ may be a more accurate description, as our results suggest that droplets became evolvable molecular aggregates — one of which became our common ancestor.”

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.