Researchers reveal a novel metal where electrons flow with fluid-like dynamics

"This novel liquid will flow inside the metal exactly in the same way as water flows in a pipe”

A team of researchers from Boston College has created a new metallic specimen where the motion of electrons flows in the same way water flows in a pipe -- fundamentally changing from particle-like to fluid-like dynamics, the team reports in Nature Communications.

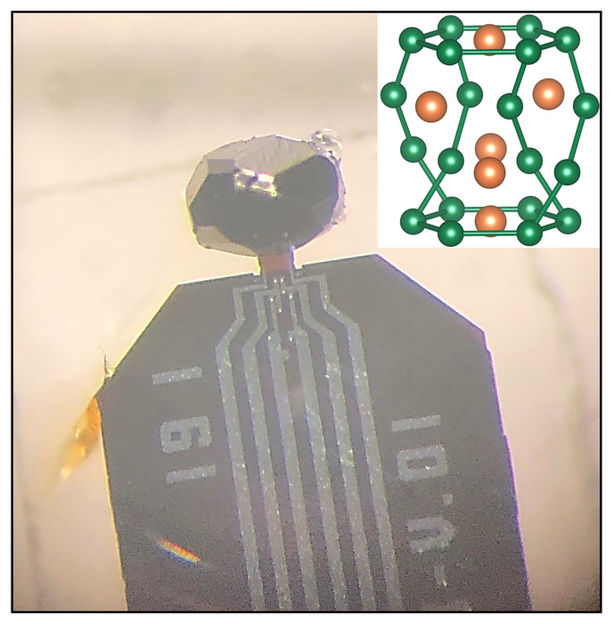

A small crystal of the new material, a synthesis of Niobium and Germanium (NbGe2), is mounted on a device to examine the behavior of the new electron-phonon liquid. The inset shows the atomic arrangement in the material.

Fazel Tafti, Boston College

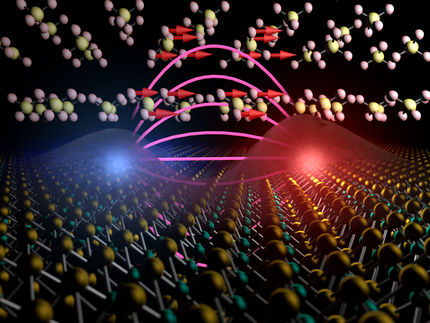

Working with colleagues from the University of Texas at Dallas and Florida State University, Boston College Assistant Professor of Physics Fazel Tafti found in the metal superconductor, a synthesis of Niobium and Germanium (NbGe2), that a strong interaction between electrons and phonons alters the transport of electrons from the diffusive, or particle-like, to hydrodynamic, or fluid-like, regime.

The findings mark the first discovery of an electron-phonon liquid inside NbGe2, Tafti said.

“We wanted to test a recent prediction of the ‘electron-phonon fluid’,” Tafti said, noting that phonons are the vibrations of a crystal structure. “Typically, electrons are scattered by phonons which leads to the usual diffusive motion of electrons in metals. A new theory shows that when electrons strongly interact with phonons, they will form a united electron-phonon liquid. This novel liquid will flow inside the metal exactly in the same way as water flows in a pipe.”

By confirming the predictions of theoreticians, the experimental physicist Tafti -- working with his Boston College colleague Professor of Physics Kenneth Burch, Luis Balicas of FSU, and Julia Chan of UT-Dallas -- says the discovery will spur further exploration of the material and its potential applications.

Tafti noted that our daily lives depend on the flow of water in pipes and electrons in wires. As similar as they may sound, the two phenomena are fundamentally different. Water molecules flow as a fluid continuum, not as individual molecules, obeying the laws of hydrodynamics. Electrons, however, flow as individual particles and diffuse inside metals as they get scattered by lattice vibrations.

The team’s investigation, with significant contributions from graduate student researcher Hung-Yu Yang, who earned his doctorate from BC in 2021, focused on the conduction of electricity in the new metal, NbGe2, Tafti said.

They applied three experimental methods: electrical resistivity measurements showed a higher-than-expected mass for electrons; Raman scattering showed a change of behavior in the vibration of the NbGe2 crystal due to the special flow of electrons; and X-ray diffraction revealed the crystal structure of the material.

By using a specific technique known as the “quantum oscillations” to evaluate the mass of electrons in the material, the researchers found that the mass of electrons in all trajectories was three times larger than the expected value, said Tafti, whose work is supported by the National Science Foundation.

“This was truly surprising because we did not expect such ‘heavy electrons’ in a seemingly simple metal,” Tafti said. “Eventually, we understood that the strong electron-phonon interaction was responsible for the heavy electron behavior. Because electrons interact with lattice vibrations, or phonons, strongly, they are ‘dragged’ by the lattice and it appears as if they have gained mass and become heavy.”

Tafti said the next step is to find other materials in this hydrodynamic regime by leveraging the electron-phonon interactions. His team will also focus on controlling the hydrodynamic fluid of electrons in such materials and engineering new electronic devices.