Producing hydrogen using less energy

International research team describes complete reaction path for electrocatalytic hydrogen generation

The way in which a compound inspired by nature produces hydrogen has now been described in detail for the first time by an international research team from the University of Jena and the University of Milan-Bicocca. These findings are the foundation for the energy-efficient production of hydrogen as a sustainable energy source.

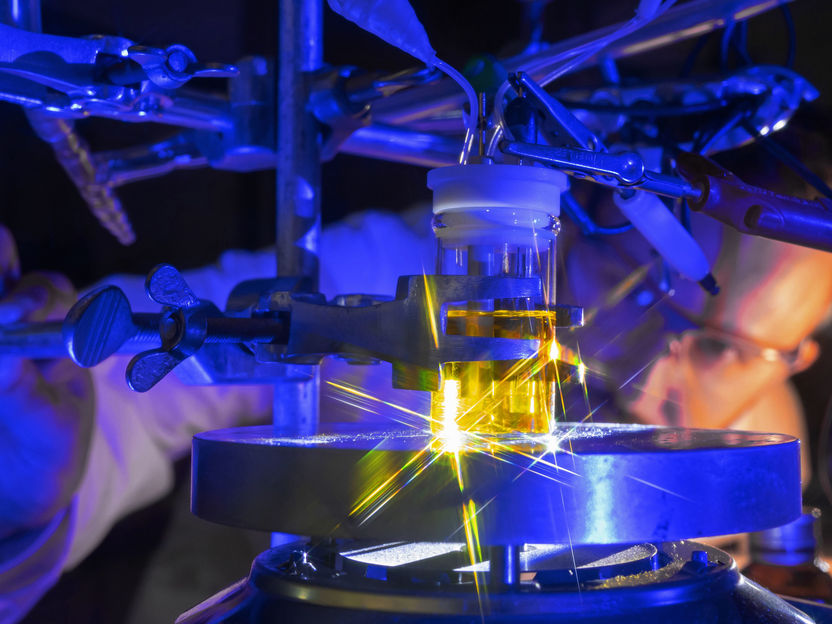

Dr. Laith Almazahreh is investigating the mechanism of electrocatalytic hydrogen formation with a nature-inspired model compound at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena.

Jens Meyer/Universität Jena

Nature as a model

There are naturally occurring microorganisms that produce hydrogen, using special enzymes called hydrogenases. “What is special about hydrogenases is that they generate hydrogen catalytically. Unlike electrolysis, which is usually carried out industrially using an expensive platinum catalyst, the microorganisms use organometallic iron compounds,” explains Prof. Wolfgang Weigand from the Institute of Inorganic and Analytical Chemistry at the University of Jena. “As an energy source, hydrogen is naturally of great interest. That’s why we want to understand exactly how this catalytic process takes place,” he adds.

In the past, numerous compounds have already been produced worldwide that are chemically modelled on the naturally occurring hydrogenases. In cooperation with the university of Milan, Weigand and his team in Jena have now produced a compound that has yielded entirely new insights into the catalysis process. “As in nature, our model is based on a molecule that contains two iron atoms. Compared with the natural form, however, we changed the chemical environment of the iron in a specific way. To be precise, an amine was replaced by a phosphine oxide with similar chemical properties. We therefore brought the element phosphorus into play.”

Detailed insight into electrocatalytic hydrogen production

This enabled Weigand and his team to better understand the process of hydrogen formation. Through autodissociation, water forms positively charged protons and negatively charged hydroxide ions. “Our goal was to understand how these protons form hydrogen. However, the proton donor in our experiments was not water, but an acid,” Weigand says. “We observed that the proton of the acid is transferred to the phosphine oxide of our compound followed by a proton release to one of the iron atoms. A similar process would also be found in the natural variant of the molecule,” he adds. In order to balance the proton’s positive charge and ultimately produce hydrogen, negatively charged electrons were introduced in the form of electric current. With the help of cyclic voltammetry and simulation software developed at the University of Jena, the individual steps in which these protons were finally reduced to free hydrogen were examined. “During the experiment, we could actually see how the hydrogen gas rose from the solution in small bubbles,” notes Weigand.

“The experimental measurement data from the cyclic voltammetry and the simulation results were then used by the research team in Milan for quantum chemical calculations,” adds Weigand. “This enabled us to propose a plausible mechanism for how the entire reaction proceeds chemically to produce the hydrogen – and this for each individual step of the reaction. This has never been done before with this level of accuracy.” The group published the results and the proposed reaction pathway in the renowned journal ACS Catalysis.

The goal: hydrogen through solar energy

Building on these findings, Weigand and his team now want to develop new compounds that can not only produce hydrogen in an energy-efficient way, but also use sustainable energy sources to do so. “The goal of the Transregio Collaborative Research Centre 234 ‘CataLight’, of which this research is a part, is the production of hydrogen by splitting water with the use of sunlight,” Weigand explains. “With the knowledge gained from our research, we are now working on designing and investigating new catalysts based on the hydrogenases, which are ultimately activated using light energy.”

Original publication

Laith R. Almazahreh, Federica Arrigoni, Hassan Abul-Futouh, Mohammad El-khateeb, Helmar Görls, Catherine Elleouet, Philippe Schollhammer, Luca Bertini, Luca De Gioia, Manfred Rudolph, Giuseppe Zampella und Wolfgang Weigand; "Proton Shuttle Mediated by (SCH2)2P═O Moiety in [FeFe]-Hydrogenase Mimics: Electrochemical and DFT Studies"; ACS Catalysis; 2021, 11, 7080-7098