Coiling them up: Synthesizing organic molecules with a long helical structure

Scientists explored the helical inversion process in the new, longer compounds

Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) produced and extensively characterized novel organic molecules with a long helical structure. Unlike previous helical molecules, these longer compounds exhibit special interactions between coils that could give rise to interesting optical and chemical properties with applications in light polarization, catalysis, and molecular springs.

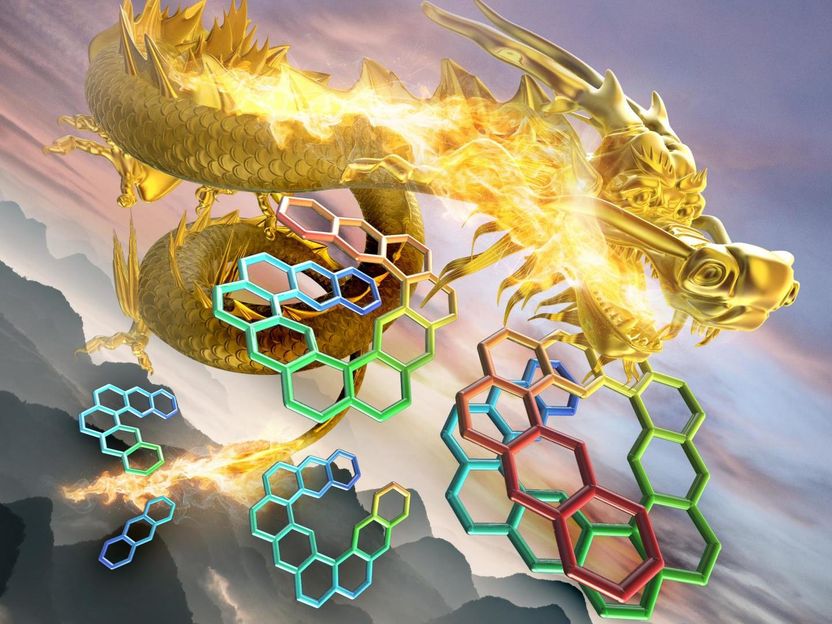

Helical molecules with a large diameter are symbolized as a spirally rising dragon.

Eiji Tsurumaki, Chemistry-A European Journal Usage Restrictions

More often than not, organic molecules with unique 3D structures bear physicochemical properties that cannot be found in other types of compounds. Helicenes, chains of simple benzene rings that adopt a helical structure, are a good example. These molecules, which resemble a spring, have interesting applications in optics and as chemical sensors or catalysts. However, it is still difficult to synthesize long helicenes; the longest one ever made was sixteen benzene rings long, which amounted to a helical structure with slightly more than two full turns and a half.

In a recent study published in Chemistry - A European Journal, a team of scientists at Tokyo Tech mixed things up by synthesizing a different type of organic molecule with a helical structure. Unlike helicenes, the basic unit of their compounds was anthracene, a linear chain of three aromatic rings (see Figure 1). In previous works, the team had managed to synthesize [3]HA, which stands for "helical anthracene with three anthracene units." However, as Professor Shinji Toyota, the corresponding author of the study, explains, "[3]HA was not long enough to reach a full turn. Therefore, it did not exhibit some of the peculiar characteristics that arise from the interactions between different 'layers' of the helical structure in a face-to-face fashion."

Using a carefully planned step-by-step process, the scientists managed to synthesize [4]HA and [5]HA, which they proceeded to characterize through a variety of experiments backed by theoretical calculations. They verified the composition and structure of the compounds using proton nuclear magnetic resonance and X-ray analysis. These findings were confirmed through density functional theory calculations, a widely used approach used to make quantum mechanical models of electronic and nuclear structures.

Then, the researchers quantified the stability of the different helical anthracenes by using them in a virtual chemical reaction that changed them into flat molecules. Interestingly, the stability of 3[HA] was almost the same as that of [4]HA and [5]HA. This indicates that the destabilizing forces that naturally appear in longer molecular chains ([4]HA and [5]HA) actually cancelled out with the new face-to-face stabilizing interactions between different helical layers. These interactions between layered anthracene moiety was visualized by Non-Covalent Interaction (NCI) analysis (Figure 32). The effect of these new interactions was also apparent in the photoemission properties of the longer molecules; their emission bands upon excitation were longer-lived, highlighting the fact that excited states were preserved longer.

Finally, the scientists explored the helical inversion process in the new, longer compounds. This inversion refers to the process of left-handed spirals changing into right-handed ones and vice versa. Some attractive optical properties such as circular polarization are lost if left- and right-handed spirals are present in equal proportion. This motivated the team to analyze the stepwise process by which each helical structure changes directions.

Overall, this study provides some much-needed insight into a new type of helical molecule. Already looking ahead, Toyota comments on future works involving these exciting compounds: "Extending helical anthracenes further and producing them with a single coiling direction remains a challenge, and so does testing their performance as molecular springs. Our team is currently working on synthesizing even longer molecules and performing structural modifications." Only time will tell what's in line for helical structures when longer ones finally spring up!

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

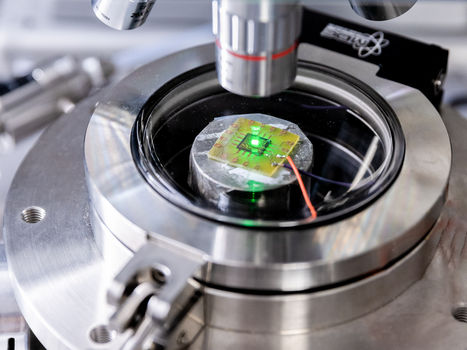

Premiere for superconducting diode without external magnetic field - Promising material graphene

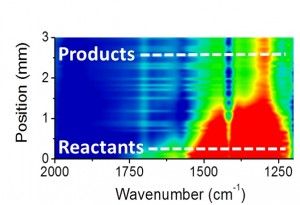

Tracking catalytic reactions in microreactors

Evolution: Building blocks of life

CD1D

Amoco