The importance of good neighbors in catalysis

Are you affected by your neighbours? So are nanoparticles in catalysts

New research from Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden, published in the journals Science Advances and Nature Communications, reveals how the nearest neighbours determine how well nanoparticles work in a catalyst.

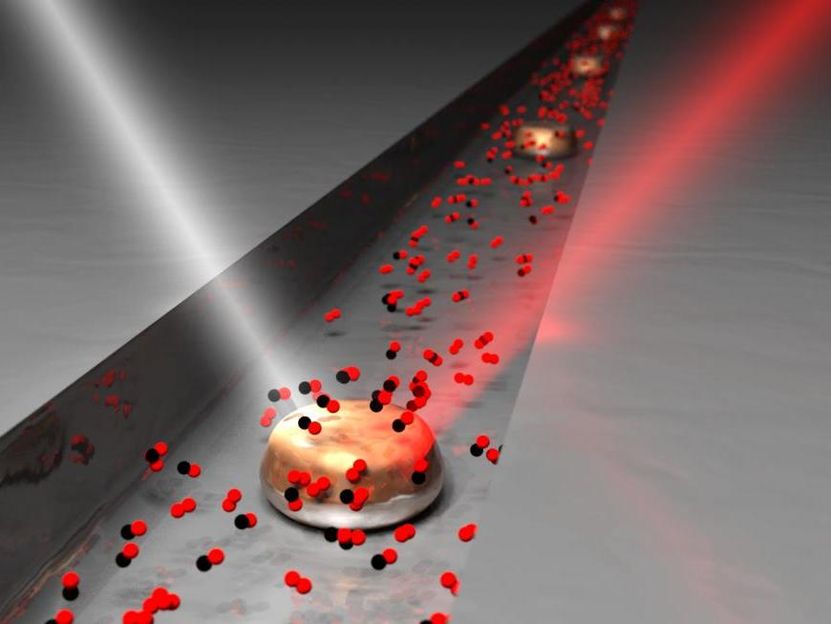

Neighbourly collaboration for catalysis. First, a number of nanoparticles of copper are isolated in a gas-filled nanotube. Researchers then use light to measure how they affect each other in the process by which oxygen and carbon monoxide become carbon dioxide. The long-term goal of the research is to find a resource-efficient "neighbourhood collaboration" where as many particles as possible are catalytically active at the same time.

David Albinsson/Chalmers University of Technology

"The long-term goal of the research is to be able to identify 'super-particles', to contribute to more efficient catalysts in the future. To utilise the resources better than today, we also want as many particles as possible to be actively participating in the catalytic reaction at the same time," says research leader Christoph Langhammer at the Department of Physics at Chalmers University of Technology.

Imagine a large group of neighbours gathered together to clean a communal courtyard. They set about their work, each contributing to the group effort. The only problem is that not everyone is equally active. While some work hard and efficiently, others stroll around, chatting and drinking coffee. If you only looked at the end result, it would be difficult to know who worked the most, and who simply relaxed. To determine that, you would need to monitor each person throughout the day. The same applies to the activity of metallic nanoparticles in a catalyst.

The hunt for more effective catalysts through neighbourly cooperation

Inside a catalyst several particles affect how effective the reactions are. Some of the particles in the crowd are effective, while others are inactive. But the particles are often hidden within different 'pores', much like in a sponge, and are therefore difficult to study.

To be able to see what is really happening inside a catalyst pore, the researchers from Chalmers University of Technology isolated a handful of copper particles in a transparent glass nanotube. When several are gathered together in the small gas-filled pipe, it becomes possible to study which particles do what, and when, in real conditions.

What happens in the tube is that the particles come into contact with an inflowing gas mixture of oxygen and carbon monoxide. When these substances react with each other on the surface of the copper particles, carbon dioxide is formed. It is the same reaction that happens when exhaust gases are purified in a car's catalytic converter, except there particles of platinum, palladium and rhodium are often used to break down toxic carbon monoxide, instead of copper. But these metals are expensive and scarce, so researchers are looking for more resource-efficient alternatives.

"Copper can be an interesting candidate for oxidising carbon monoxide. The challenge is that copper has a tendency to change itself during the reaction, and we need to be able to measure what oxidation state a copper particle has when it is most active inside the catalyst. With our nanoreactor, which mimics a pore inside a real catalyst, this will now be possible," says David Albinsson, Postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Physics at Chalmers and first author of two scientific articles recently published in Science Advances and Nature Communications.

Anyone who has seen an old copper rooftop or statue will recognise how the reddish-brown metal soon turns green after contact with the air and pollutants. A similar thing happens with the copper particles in the catalysts. It is therefore important to get them to work together in an effective way.

"What we have shown now is that the oxidation state of a particle can be dynamically affected by its nearest neighbours during the reaction. The hope therefore is that eventually we can save resources with the help of optimised neighbourly cooperation in a catalyst," says Christoph Langhammer, Professor at the Department of Physics at Chalmers.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

NANOPHOX CS by Sympatec

Particle size analysis in the nano range: Analyzing high concentrations with ease

Reliable results without time-consuming sample preparation

Eclipse by Wyatt Technology

FFF-MALS system for separation and characterization of macromolecules and nanoparticles

The latest and most innovative FFF system designed for highest usability, robustness and data quality

DynaPro Plate Reader III by Wyatt Technology

Screening of biopharmaceuticals and proteins with high-throughput dynamic light scattering (DLS)

Efficiently characterize your sample quality and stability from lead discovery to quality control

Get the chemical industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Category:Liquid_crystals

List_of_minerals_N-R_(complete)

Tyrosine

Category:Samarium_compounds

Category:Bronchodilators

How organic solar cells could become significantly more efficient - Turbocharger dyes: Organic dyes accelerate transport of buffered solar energy

Estée_Lauder_Companies

CBV_(chemotherapy)

Labfolder signs agreement with Max Planck Society - Contract provides up to 11,000 Max Planck scientists access to use labfolder for digital laboratory data management

Museum_of_Neon_Art

Johann_Rudolf_Glauber